Hand-painted celluloid revives golden days of early Chinese cinema

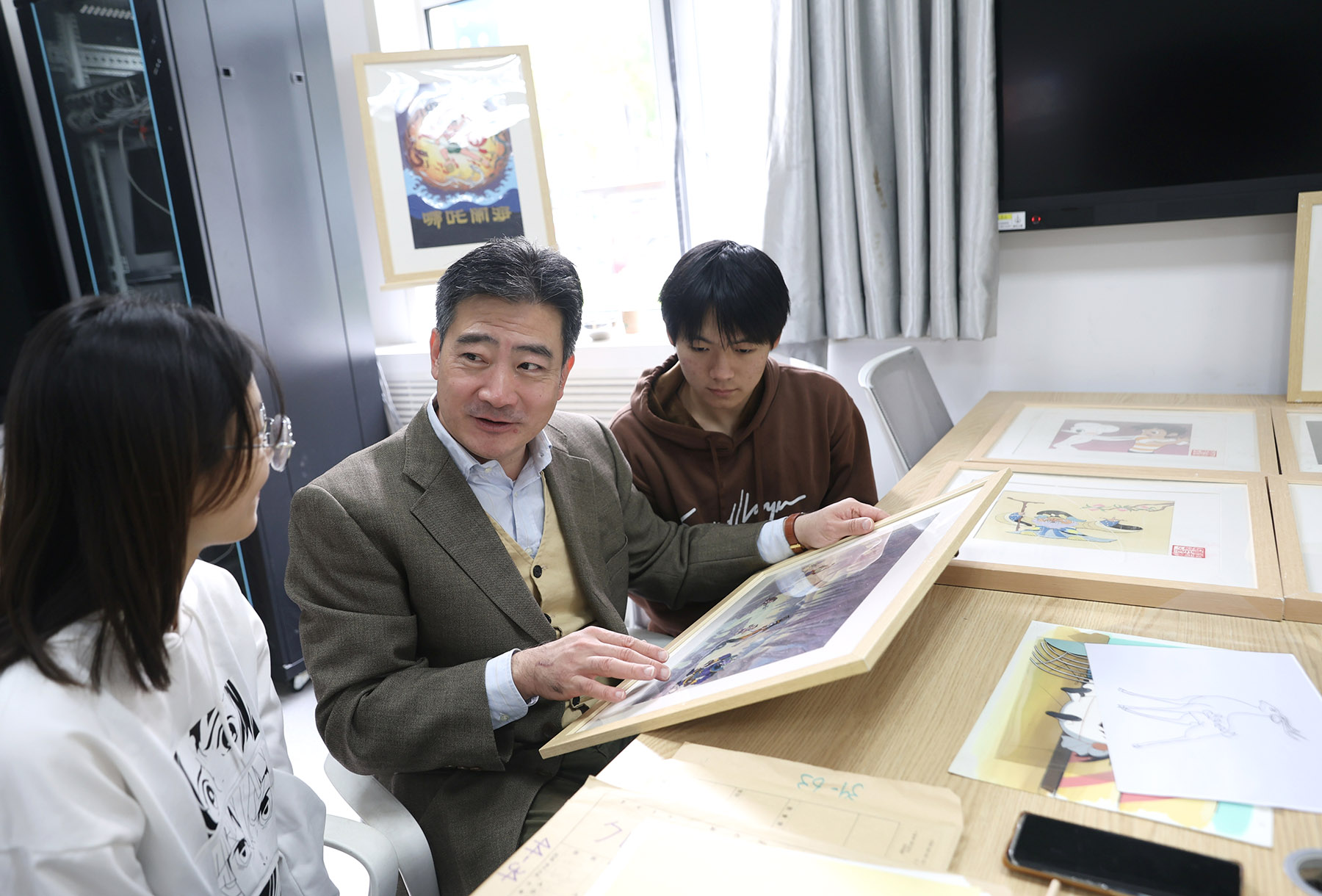

In the dimly lit corner of a modest studio, Zhao Lei leans over a large wooden desk as his fingers delicately trace the outline of a character on a translucent sheet of celluloid.

Zhao's meticulous craftsmanship and pursuit of perfection are keeping alive a technique nearly abandoned in the age of digital filmmaking.

Each frame of an animation is drawn by hand on transparent sheets known as cels. These cels are then layered over static backgrounds and photographed in sequence to create the illusion of motion.

"There is something in traditional animation that digital technology can never replicate," Zhao said. "It carries the soul of the artist, the touch of the hand, and that's something truly irreplaceable."

READ MORE: Animated feature tops nation's all-time box office charts

After Zhao completes the line work, the cels are painted on the reverse side, with acrylic or enamel paints used to color the character.

The image Zhao has drawn is a magical nine-colored deer, the lead figure in The Nine-Colored Deer, a 24-minute animated film produced by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio and released in 1981. Adapted from murals in Dunhuang Grottoes in Dunhuang, Gansu province, the film tells the story of a spiritual creature that saves a businessman from drowning in a river.

The studio, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2017, said a five-member creative team from Shanghai spent more than 20 days in Dunhuang, gaining inspiration for the film. Copying the murals, they drew about 20,000 pictures, with 200 of them chosen for film scenes.

"In cel animation, the final result — especially when it comes to how the colors and lines will look in the finished scene — isn't fully visible until the entire drawing and painting process is completed. This can make the technique particularly challenging and unpredictable for animators," said Zhao while coloring the deer image.

He said unpredictability of color, the drying process, and how different layers interact make cel animation both a beautiful and risky art form.

"It requires expertise, careful planning, and test shots to ensure the final result looks just as the animator envisioned. It's one of the reasons why traditional cel animation is considered such a time-intensive and delicate process," he said.

Golden era

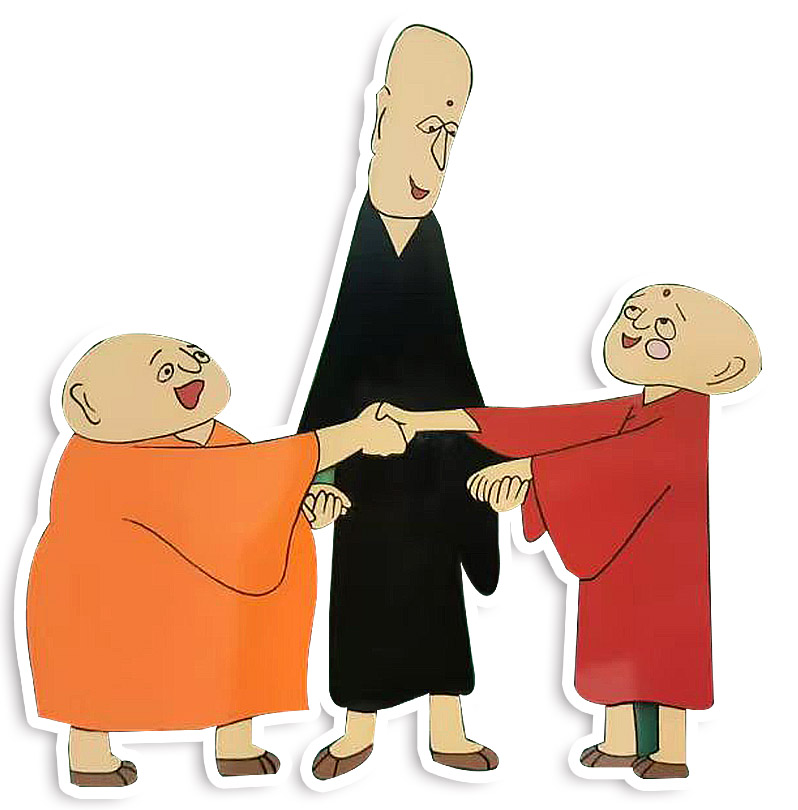

Chinese animation has a history of over 100 years, starting with the three Wan brothers — Laiming, Guchan, and Chaochen — who produced the country's first animated films in the 1920s.

In 1957, China established its first animation studio — Shanghai Animation Film Studio, starting the "golden era" of Chinese animation.

One of the best-known animations produced by the studio was The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven, China's first color animated feature film made from 1961 to 1964. The film, inspired by the 16th-century novel Journey to the West, helped Chinese animation get a foothold on the global stage.

A five-second animated scene can hide the complexity of hundreds of drafts behind it, Zhao said. "This 'manual labor' is exactly what produced some of the classic moments in Chinese animation," he said.

The story of Zhao's connection to cel animation began in the late 1990s, when he was a young man captivated by the magic of the animated movie, Lotus Lantern, by Shanghai Animation Film Studio, which featured vibrant colors and stunning hand-drawn frames.

Released in 1999, the animation was inspired by a Chinese folktale about a boy named Chen Xiang saving his mother, a fairy, whose forbidden love with his mortal father is frowned upon by the deities.

He had grown up watching classic animations such as The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979), and The Legend of Sealed Book or Tianshu Qitan (1983), and it had been 15 years since the studio had released a major production.

"It had been a very long time since the Shanghai Animation Film Studio had released a new animated movie. It felt like my childhood was coming back, which made me very excited," recalled Zhao.

What made Zhao even more excited was that the same year the studio took in its first batch of students after it launched a course on animated films.

Zhao enrolled and soon encountered the cel animation technique and his lifelong calling.

As his instructor demonstrated the painstaking process of drawing characters on transparent sheets of celluloid, Zhao was struck by the beauty of the technique.

"The colors were so vivid, the shapes so alive," he recalled, adding that his teachers were recently retired veteran animators from the studio.

"And when you added the background, the image had a natural depth, a kind of layer that digital techniques can't replicate," he said.

Preserving art form

As the world of animation rapidly shifted toward computer-generated imagery, cel animation, once the backbone of the industry, began to fade.

But the memory of those vivid images on celluloid remained with Zhao, and he knew that this technique, with deep roots in Chinese animation history, had to be preserved.

"It was something I loved deeply," he said. "This technique, this tradition, it couldn't just disappear."

In 2004, Zhao, who had worked for a Chinese animation movie production company, got a job teaching at Beijing New Media Technical College's animation department, which allowed him to pass on his knowledge and love of cel animation to a new generation.

But reviving cel animation was far more difficult than Zhao had anticipated.

Many of the paints, tools, and materials used in the process had been discontinued. Suppliers no longer produced the necessary pigments, and most of the senior animators who had mastered the craft had long since retired or left the industry.

Zhao found himself in a daunting position. Determined to find a way forward, he turned to original animation cels he purchased from various sources, to study and experiment. Each day, he would test different materials, research the proper techniques, and correct mistakes he had made.

"I spent a lot of time stumbling," Zhao said. "But every failure taught me something new."

Slowly, through trial and error, he began to develop his own process for cel animation, carefully calibrating the water-to-pigment ratio to create the perfect consistency. The process wasn't just technical. It required an acute understanding of how light and color interact.

"You have to account for how different lighting conditions affect color perception," Zhao explained. "The best time to mix colors is at noon, under natural sunlight, with no color bias in the environment."

Even the humidity and the state of the paint — whether it was wet or dry — played a crucial role.

"When the paint dries, the color deepens. So you have to mix a lighter shade in anticipation of the final result," he added. This precision was something only years of practice could perfect.

For Zhao, it wasn't just about replicating the technique; it was about understanding the soul of cel animation. "Traditional animation was born on paper. Even as we entered the age of digital animation, and even now as AI takes over, hand-drawn animation feels like it has become a thing of the past. But what it carries — that delicate line work, the exact control of color — is the very essence of Chinese animation," he said.

Zhao and his students have revived the process to a point where their cel animation productions now replicate the original technique with more than 90 percent accuracy.

"From outlining to coloring, to painting backgrounds, it's almost indistinguishable from the original," he said with pride. "We've reached a level where we can recreate the process almost exactly as it was done decades ago."

Passing the baton

His students, eager to learn this nearly forgotten art, come from varied backgrounds, and are curious and excited to master the traditional skills that Zhao Lei has painstakingly revived. "It's a tough process. The demands are high — lines have to be smooth, precise, firm, and alive. Coloring needs to be flawless. Every detail matters," said Shen Jie, a student at Beijing New Media Technical College.

In September, Zhao, along with his students, including Shen, participated in the Third Vocational Skills Competition in Zhengzhou, Henan province, that featured 3,420 competitors from 35 delegations competing in 106 events.

They showcased the cel animation technique, which gained recognition during the competition, China's highest-level, largest, and most influential national vocational skills event.

Later, the team traveled to Nanjing, Jiangsu province, to join in a Monkey King-themed exhibition held at Jiangsu Art Museum, displaying their replicas of the artwork from the classic animated movie, The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven.

What makes Zhao most proud, however, is not just the technical mastery he has passed on to his students. It's the fact that many of the young people are now using the technique of celluloid animation in their schoolwork, while some directors are including cel animation in their movies, which allows more people to appreciate the art form.

Xie Xinyi and Shen Yuting, two students from the Film-Television and Communication College of Shanghai Normal University studying animation, have been creating their own celluloid animation works.

Their ongoing animated movie project — The Legend of Fox — blends traditional cel animation with digital tools. The pair had initially planned to make the entire movie using cel animation, but encountered significant technical challenges.

"It's difficult to find the right tools and resources, so we decided to combine traditional cel animation with digital techniques, adding special effects to enhance the final product," said Shen.

"Nothing captures classic storytelling like the warm, textured feel of cel animation," she added. "The imperfections and subtle variations in hand-drawn animation make characters feel more lifelike and emotionally resonant."

Xie and Shen, both aged 19, grew up watching Chinese animation movies, such as the Calabash Brothers.

"The unique art style, memorable characters, and engaging storyline marked a distinct departure from digital cartoons," said Xie.

The 13-episode Calabash Brothers, originally screened from 1986 to 1987, was her first encounter with the works of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, and inspired her future career choice.

Xie and Shen's passion for animation led them to explore the traditional techniques of animation production, aided by the university's emphasis on traditional hand-drawn animation processes, including cel animation.

"Every step in the traditional animation process, like painting each frame by hand, feels like creating a piece of art," Xie said.

"It's like cooking; the order and technique matter. Even the smallest difference in coloring can change the whole frame."

Both are also keenly aware of the growing wave of Chinese animated films and the increasing popularity of domestic productions like Ne Zha and its sequel, Ne Zha 2, the highest-grossing film in Chinese history. The ink-wash animated movie, Nobody, inspired by Journey to the West and produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio — also swept the box office this summer.

"These movies are helping place Chinese animation firmly in the global spotlight and are attracting many young people to Chinese animation movies made with traditional techniques," said Shen.

Contact the writers at chennan@chinadaily.com.cn