Intellectuals and artists collaborate on personalized stationery, adding a human touch to the unique tradition of huajian, which celebrates fine papermaking skills and printing workmanship, Lin Qi reports.

In the age of social media, the photos and images used in people's profiles have become a shield for introverts to participate in online socializing, or a personality statement, aesthetic preference, or fleeting emotion as their avatar changes from time to time.

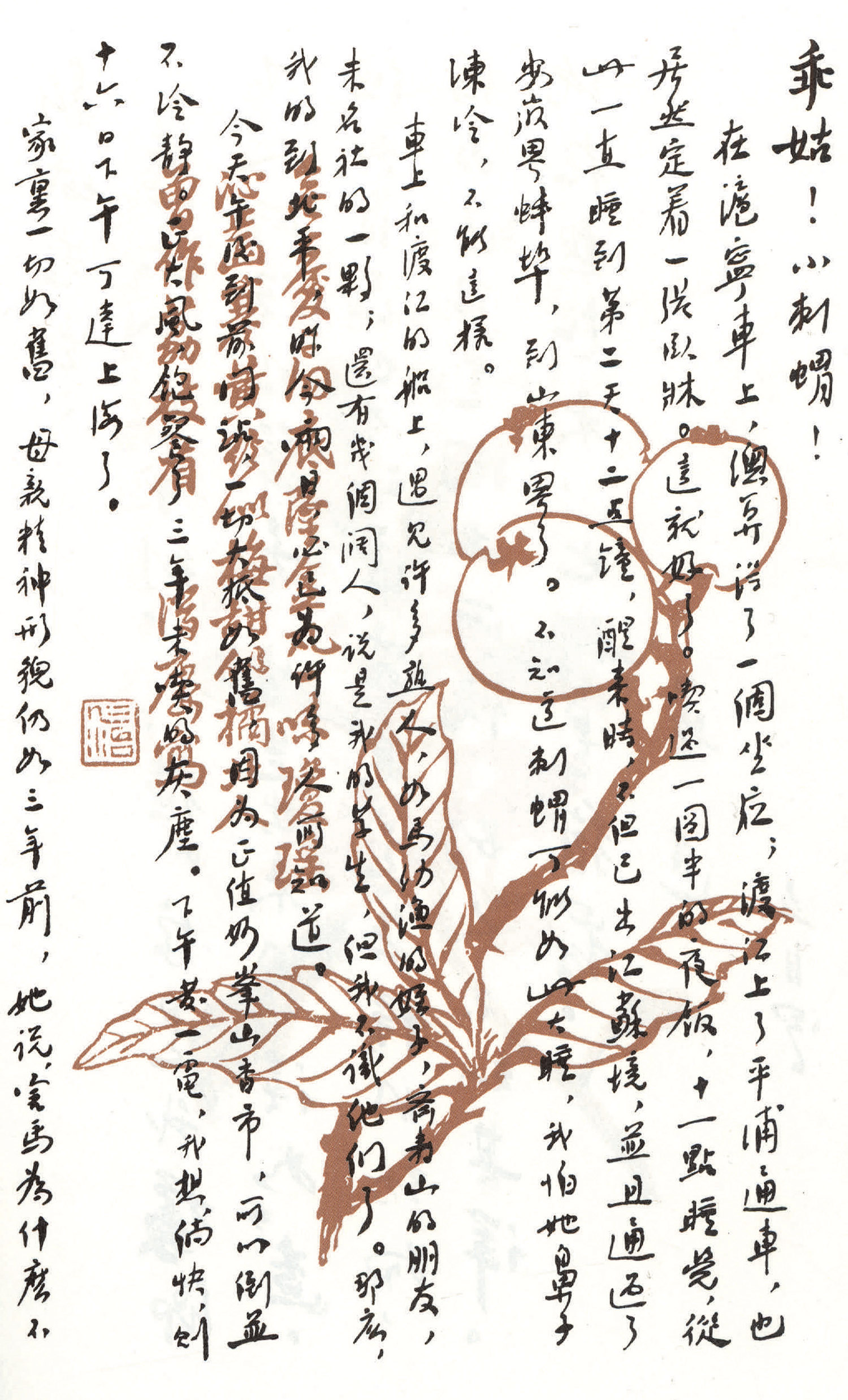

However, in ancient times, people relied heavily on exchanging letters and brief notes for communication. Intellectuals and artists felt that writing or drawing on white paper was far from fully offering an expression of their thoughts and literary and artistic tastes. Thus, they designed a special type of patterned paper called huajian, ordered studios to print the paper, and decorated it with customized motifs and characters, on smaller-sized sheets.

From the Tang Dynasty (618-907) poets who initiated this elegant trend to Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), who took pride in his majestic taste, and modern literary figures of repute like Lu Xun, they all shared enthusiasm for personalized paper art. Each contributed to the flourishing of this small craft, which celebrated China's fine papermaking and printing workmanship spanning centuries.

Rarely seen examples of the unique huajian tradition fused with the human touch are on show at the Art Museum of Beijing Fine Art Academy.

From Where the Fine Letters Fly, an exhibition running until March 15, displays colorful, patterned vintage paper, selected huajian catalogs, and planks and tools for woodcut printing. The objects are gathered from the collections of eight museums and cultural institutions, including the Palace Museum, the Suzhou Museum in Jiangsu province, and Rong Bao Zhai, Beijing's time-honored brand in fine papermaking and woodcut printing.

The exhibition charts the evolving aesthetics of intellectuals and high society, and reflects innovations in papermaking and printing techniques. When not printed with words, these patterned papers are worthy of appreciation as stand-out miniature paintings.

Jian, slices of bamboo for writing on, were easy to carry around. After paper was invented, the term jianzhi (zhi means paper) came to refer to these finely made paper sheets on a smaller scale, meant for writing letters and poetry.

"Huajian paper embodies the beauty and depth of knowledge about Chinese culture and art," says Wu Hongliang, director of the Beijing Fine Art Academy.

"This unique stationary carries a galaxy of emotions. The patterns are like background music on paper, though they cannot be heard. They do not take attention away from the texts, but possess a lingering charm, reminding people today of the creative artistry and sincerity between the lines," Wu adds.

Xue Tao, a Tang Dynasty poet and musician, championed this graceful paper type. While she lived in Chengdu, Sichuan province, she developed a fashionable technique for dyeing paper with juice extracted from hibiscus flowers. It is believed that she fetched the water from a well in the Baihuatan Garden in Chengdu for crafting the red-hued paper.

Thus, a tiny paper of varying red hues was called "Xue Tao Jian", a term given for its delicate quality and understated beauty.

Xue created the colored paper not only to display her personal taste, but also because it was accessible to women and low in cost compared to regular-sized paper. She wrote poems and letters to her intellectual friends such as Bai Juyi, as well as Yuan Zhen, with whom she had a love affair.

Xue Tao Jian paper no longer exists, but the style has been duplicated with more colors. For example, the exhibition shows photos of two Xue Tao Jian-style sheets ordered by Pan Shi'en, a high-ranking Qing Dynasty court official, for family correspondence, one in light red and the other in yellowish brown. They can be viewed in the collection from the Shanghai Library, where there are also blue Xue Tao Jian, once used by Pan.

The Song Dynasty (960-1279) at its cultural peak in Chinese history is also evident in huajian art. Motifs diversified to include fruits, floral blossoms on tree branches, insects, landscapes, and characters inscribed on archaic bronzes, among others. A distinctive relief became popular at the time, which rendered slightly elevated patterns on paper.

Xue Liang, head of the exhibition's curatorial team, says many literary personas in the Song Dynasty, such as the great poet Su Shi and esteemed calligrapher Huang Tingjian, were involved in the design and printing of their own huajian paper. Xue says the patterns they created were sometimes so subtle that they could only be discerned and appreciated by viewing the paper from different angles.

Wu, the director, says the patterned paper reminds him of Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) literati Wen Zhenheng's best-known work, Treatise on Superfluous Things (Zhangwu Zhi), which is noted as an encyclopedia of how well-educated members of society lived a materially rich cultural life.

"Wen meticulously described every tree, flower, book, and painting. Underneath, he was investigating the relationships between objects and people in social development and in the course of history,"Wu adds.

He says huajian paper may also be seen as superfluous, but when people continue to seek an elegant lifestyle manifested in refined objects imbued with genuine emotion, these tiny sheets of paper remain essential to cultural life.

That sentiment motivated the birth of Shizhuzhai Jianpu (Ten Bamboo Studio Letter Paper Design Collection), highly recognized as a pinnacle of the huajian paper art. Supervised by Ming Dynasty publisher Hu Zhengyan, four volumes cataloged over 280 illustrations rendered with rich colors and vivid imagery, owing to collaboration between scholars, artists and master engravers.

Emperor Qianlong, an avid art patron, was also active in promoting this artistic paper. On show are two majestic examples from his reign, from the Palace Museum's collection: a piece of pink paper featuring subtle cloud patterns outlined in gold, for daily use; and a red square sheet depicting four golden dragons chasing a fireball in the center, for the monarch to write the character fu (blessing) during Chinese New Year celebrations.

In the early 20th century, renowned ink artist Qi Baishi also illustrated huajian for himself and his friends. In 1933, Lu Xun and his scholar friend Zheng Zhenduo coproduced Beiping Jianpu (Collection of Letter Papers from Beiping — Beijing was once called Beiping), which cataloged exquisite works by renowned artists of the time and made by reputed studios, thereby honoring aesthetic sensibilities and the spirit of craftsmanship.

The distinctive huajian art on paper corresponds to the saying, "zhiduan qingchang", meaning the paper is limited in space, while the words produce sound resonance.

"Indeed, the beauty of huajian will never fade, and its true essence will endure,"Wu says.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn