County blends red heritage, natural landscapes, storytelling, and modern tourism to revive memory, Yang Feiyue reports in Huichang, Jiangxi.

Standing atop Panshan Mountain in Huichang county, eastern Jiangxi province, the view commands instant awe. The jagged formations of Danxia rock rise sharply on all sides, the cliffs cut by time and weather into dramatic shapes. A single stone path winds its way up the mountain from the southwest.

The summit is unexpectedly flat and expansive, covered in verdant pine trees and bamboo, resembling a vast circular disk.

Zhong Weili, a tour guide in her 20s, draws our attention to a stone tablet facing the cliff and recounts a story of heroic sacrifice that is etched into the mountain itself.

"We are standing at the site where Red Army soldiers made their desperate leap off the cliff," Zhong says, her voice visibly stirred, a stark departure from the calm precision with which she had moments earlier described the surrounding landscape.

The events she recounts unfolded in April 1934, during the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. At the time, a lesser-known yet deeply heroic chapter of resistance was playing out across the Central Revolutionary Base, centered on neighboring Ruijin county in Jiangxi, covering areas in present-day southern Jiangxi, western Fujian and northeastern Guangdong provinces.

READ MORE: Huichang theater villages a stage for more vibrant future

As Kuomintang forces launched a fierce attack on the Red Army's southern gateway, a small unit found itself trapped at Pangu Pass, a narrow and treacherous gap at the foot of Pangu Mountain.

For three days and nights, the soldiers fiercely resisted the enemy, inflicting heavy casualties. The rugged terrain of Pangu Mountain, with its steep cliffs and narrow paths, gave the defenders some advantage, allowing them to hold their ground.

But the balance eventually tipped. As enemy reinforcements arrived and ammunition dwindled, retreat became inevitable. To cover the withdrawal, a handful of Red Army soldiers volunteered to stay behind. When the only remaining escape route was cut off, they were cornered at the mountain's peak, with no way out.

In a final act of defiance, some soldiers volunteered to stay behind to delay the enemy. After exhausting their ammunition, they fought with rocks and their bare hands. When resistance became impossible, the remaining soldiers chose death over capture, leaping from the cliff rather than surrender.

As Zhong reaches this part of the story, her voice breaks. She falls silent for several seconds, eyes lowered, allowing the weight of the moment to settle.

Even after recounting this episode countless times over more than three years, the emotional toll remains visible.

"This story may not be as widely recognized as that of the Five Heroes of Langya Mountain (who also jumped off a cliff in 1941 to fight a Japanese ambush in northern Hebei province), but it reflects the same extraordinary bravery and sacrifice," Zhong says.

To this day, military remnants from the Pangu Mountain battle are preserved on the mountain, serving as a testament to this historic event.

Zhong says she has noticed a steady rise in visitor numbers and public awareness in recent years, thanks to local efforts to improve access and interpretation.

Panshan has undergone tangible improvements in the past few years, with infrastructure upgrades.

"This path used to be difficult to walk on, especially when it rained," Zhong explains, pointing to the well-maintained stone trail beneath our feet.

"Now, it's much wider and safer, allowing more visitors to access this important site."

Additionally, safety railings were installed and monuments restored, transforming the once muddy and hazardous trails into accessible and visitor-friendly routes.

Beyond its revolutionary history, the area is also prized for its natural beauty. Seas of clouds at sunrise attract photographers, while nearby waterways offer boat rides for leisure seekers. Zhong and her colleagues have learned to weave history into nature-based itineraries.

"During the boat ride, we discuss the Danxia landforms, and once we reach the base of Panshan, we share its red history," she says.

Panshan is only one part of Huichang's broader efforts to tap into its rich revolutionary resources and preserve its cultural heritage.

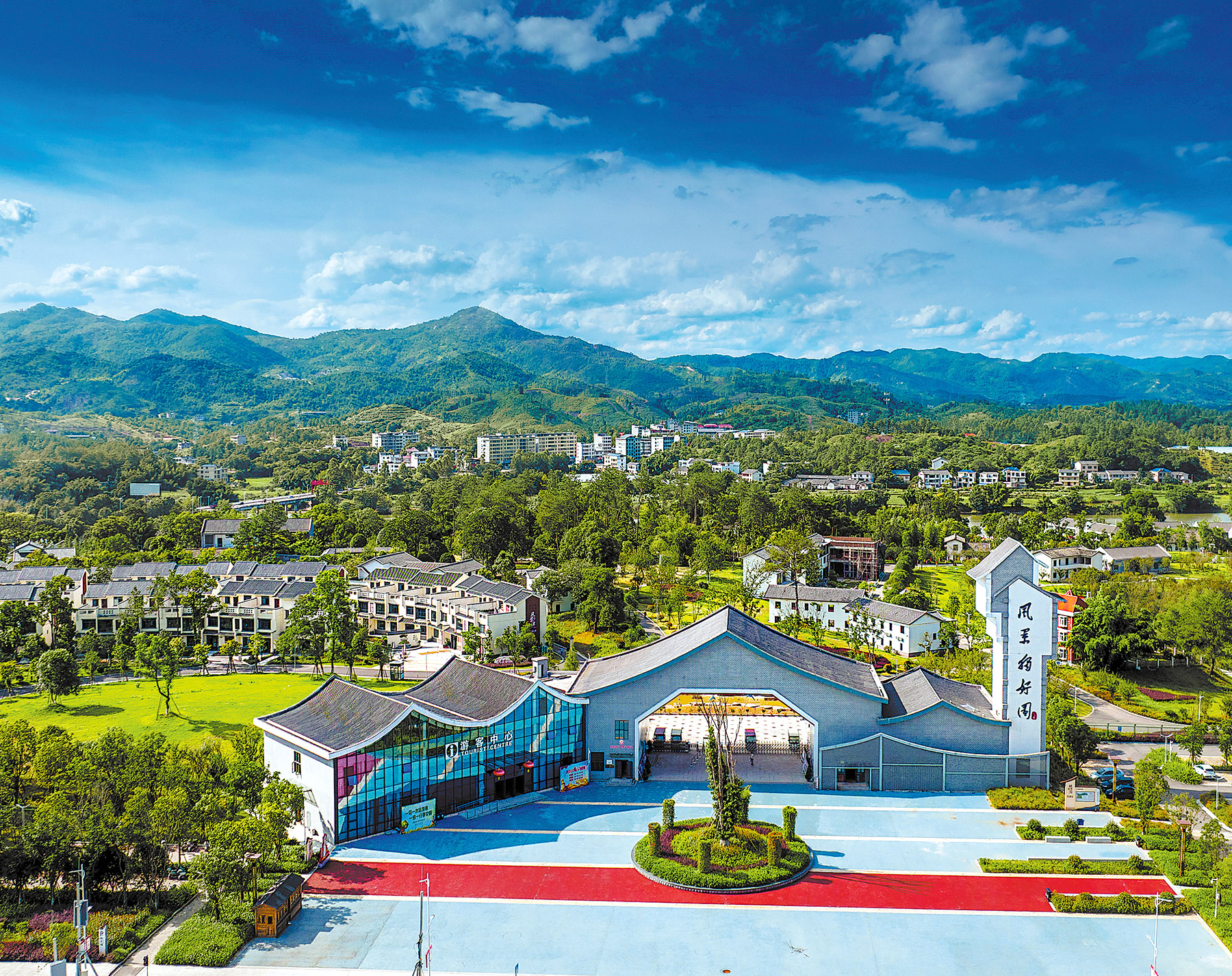

About a 40-minute drive north lies Fengjing Duhao Park, a sprawling cultural complex that blends historical memory with pastoral calm.

"This name is derived from Chairman Mao's poem Qing Ping Yue Huichang, written in Huichang during the summer of 1934," explains Zhang Yiqun, a staff member with the park's administration.

"It was his final poem composed in the Central Revolutionary Base, and the only one named after a county," she adds.

In the spring of 1934, the Red Army faced mounting pressure as the KMT forces tightened their encirclement of the Central Revolutionary Base. Huichang, on the southern front, was plunged into crisis after key positions fell.

Mao Zedong arrived to assess the situation, shifted the Red Army from static defense to flexible guerrilla tactics, and helped stabilize the front. As the southern line revived while other fronts faltered, Mao described it as fengjing duhao, meaning "the scenery here is uniquely fine".

Inspired by this moment, he climbed Huichang Mountain, which is a 10-minute drive away from Fengjing Duhao Park and wrote his final lyric before leaving the area.

Covering an area of 42 hectares, the park integrates six provincial-level cultural heritage sites, including Mao Zedong's former residence and the former headquarters of the Guangdong-Jiangxi provincial committee.

Traditional Hakka-style architecture has been carefully preserved through the restoration of facades and interior spaces of historic houses.

Eight exhibition halls built on historical architecture were dedicated to pivotal events and figures in China's revolutionary history, including the Nanchang Uprising, the Huichang campaign, the Red Army's influence in Huichang, as well as traces left by Mao Zedong and the reform and opening-up policy's chief architect Deng Xiaoping.

The exhibits utilize cutting-edge digital technologies that take one back to the tumultuous times with holograms, immersive experiences, and interactive visitor systems.

In front of Mao Zedong's former residence, Zhang pauses.

"From April to July 1934, Chairman Mao stayed here for more than three months. Despite being marginalized at the time, he never stopped paying attention to the revolutionary cause," she says.

Inside, the room is stark. A rusty kettle, a simple basin and wooden racks reflect the harsh living conditions of the time, underscoring the resolve behind historic decisions.

In addition to the rich collection of revolutionary relics, the park has evolved into a modern getaway. A cluster of restored traditional folk residences and intangible cultural heritage workshops bring local folk arts and Hakka traditions to life.

A waterside area has created a relaxed dining zone along the river, while new sports and recreation facilities, including an extreme-sports park and family play areas, add youthful energy to the grounds.

The science and agriculture section further expands the site's educational role by providing hands-on experiences in modern farming and rural studies.

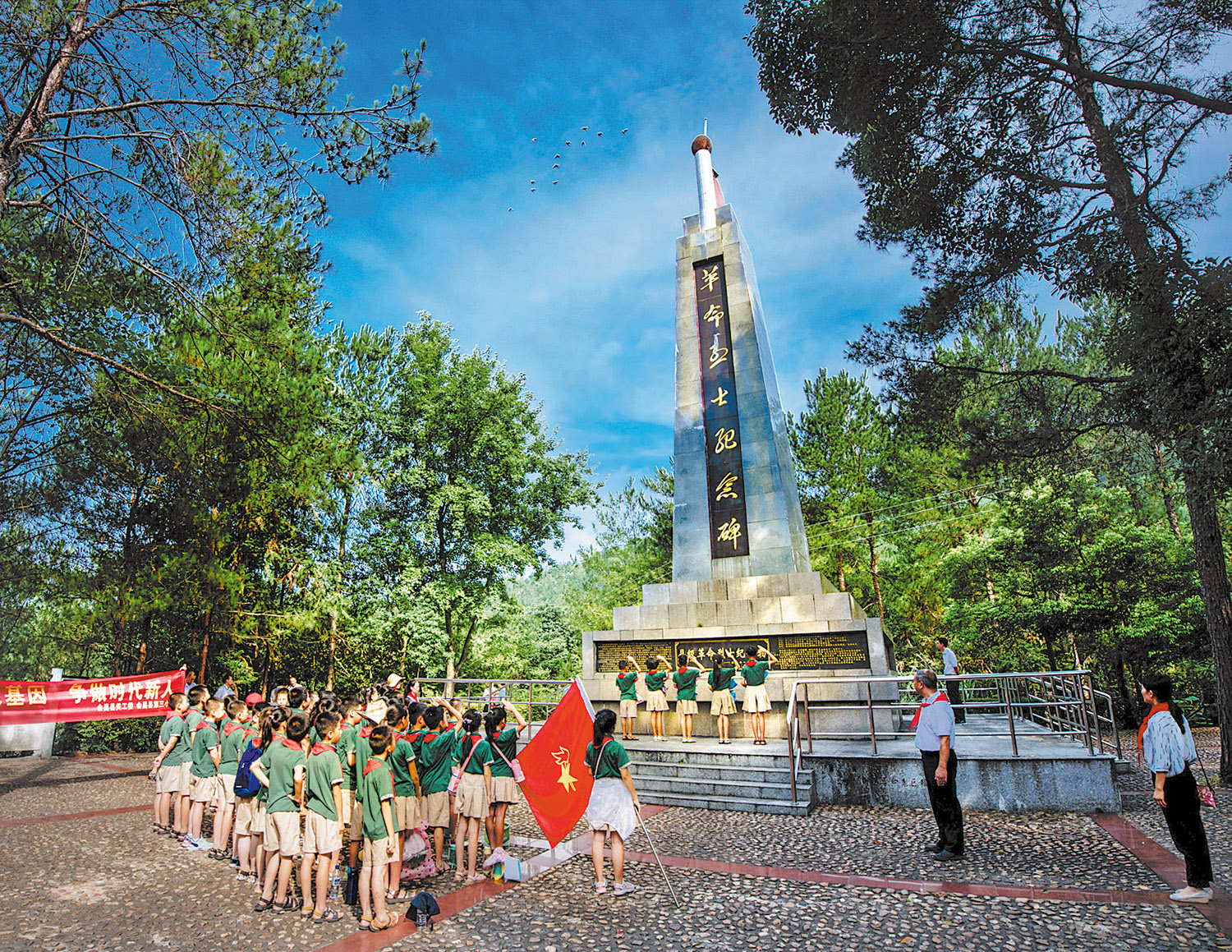

"Our park serves two distinct visitor segments," says Hu Hongmei, a tour operations staff member.

For government and enterprise delegations focused on Party history education, the experience revolves around guided tours of eight exhibition halls and revolutionary sites like the former residences.

"These are typically one-day programs with structured learning components," she says.

For educational tours for students, a progressive program has been arranged.

"We begin with age-appropriate revolutionary storytelling, then transition to cultural experiences at our traditional Chinese culture center, and conclude with hands-on rural activities," she says.

During peak seasons, those learning programs can accommodate 500 to 600 visitors daily.

Since officially opening in June 2021, the park has received over 2 million visitors, its administration reports.

Most are study groups or red education teams from within the province, as well as those from Guangdong, Fujian, Hong Kong and Macao.

Hu says tours continue to evolve. "Educational content must be updated," she says. "We're constantly developing new courses based on real site conditions and teaching needs."

Together, Panshan and Fengjing Duhao Park form part of Huichang's "one belt, three zones" tourism development strategy.

The Xiangjiang-Gongjiang scenic belt links riverside attractions, while the southern zone offers nature and wellness, the central zone provides cultural and creative experiences, and the northern part centers on learning and rural leisure.

ALSO READ: Teaching the stage in a different way

According to Wu Yang, deputy director of the Huichang revolutionary heritage protection and development center, Huichang is home to 67 identified immovable revolutionary relics.

Since 2016, Huichang has invested about 100 million yuan ($14.2 million) to restore 24 major revolutionary sites, including Mao Zedong's former residence.

"We encourage creative approaches to heritage use, highlighting the contemporary value of revolutionary relics," he says.

"By integrating preservation with red tourism, rural vitalization, and local industry, the county is improving public well-being and driving socioeconomic development, allowing its historic sites to speak anew," he adds.

Wu points out that Huichang's extensive revolutionary heritage remains central to understanding the region's past and its ongoing development.

"These sites help explain why Mao once called Huichang 'a place where the scenery is uniquely fine', and they continue to offer new ways for people to connect with the history that shaped our county," he says.

Contact the writer at yangfeiyue@chinadaily.com.cn