Su stitching techniques give needlework remarkable dimensionality, creating dialogue with multiple generations, Wang Qian reports.

From a distance, the artwork appears to be a serene, monochrome rendering of bamboo and rock framed within a classical garden window in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. Only by moving closer, within inches of the silk, is the creation's true ambition revealed. Each subtle shift in texture, each variation in the light, uncovers a different technique. Forty techniques in total, a millennium of Su embroidery knowledge is condensed into a single square.

"It is a concentration of my life in this art," says Zou Yingzi, 53, the master artisan behind the work. For her, the piece, Zhushi Tu (bamboo and rock picture), is a manifesto that shows an ancient craft, perfected over 1,000 years, can still whisper startlingly new ideas.

READ MORE: Following the patterns of history

Running through Friday at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, The Path of Master: Zou Yingzi's Su Embroidery Exhibition showcases 20 artworks that are less about display and more about dialogue. "They converse across centuries, between the loom and the lens, the sacred and the everyday," Zou says.

Born in Zhenhu in the west of Suzhou's new district, known as the cradle of Su embroidery, Zou began learning the technique at the age of 6 beside her mother's embroidery frame. Dating back more than 3,000 years, the craft originated in the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280), and double-sided embroidery is one of its excellent examples.

"I learned the language of the needle before I fully learned my own," she says. That foundational fluency allowed her to become an innovator. Her patented didi stitch, or drop-by-drop stitch, uses points mere fractions of a millimeter apart to create a surface that seems to breathe.

"It gives embroidery a sense of respiration, a matte elegance," she says.

Her pioneering work has drawn the attention of scholars. "In my opinion, Zou is one of the most genuinely creative representatives of Su embroidery today," says Shang Gang, a retired professor from Tsinghua University's Academy of Arts and Design. "She has transformed needlework from a craft into a true art form that expresses ideas, giving flat embroidery a remarkable, living dimensionality."

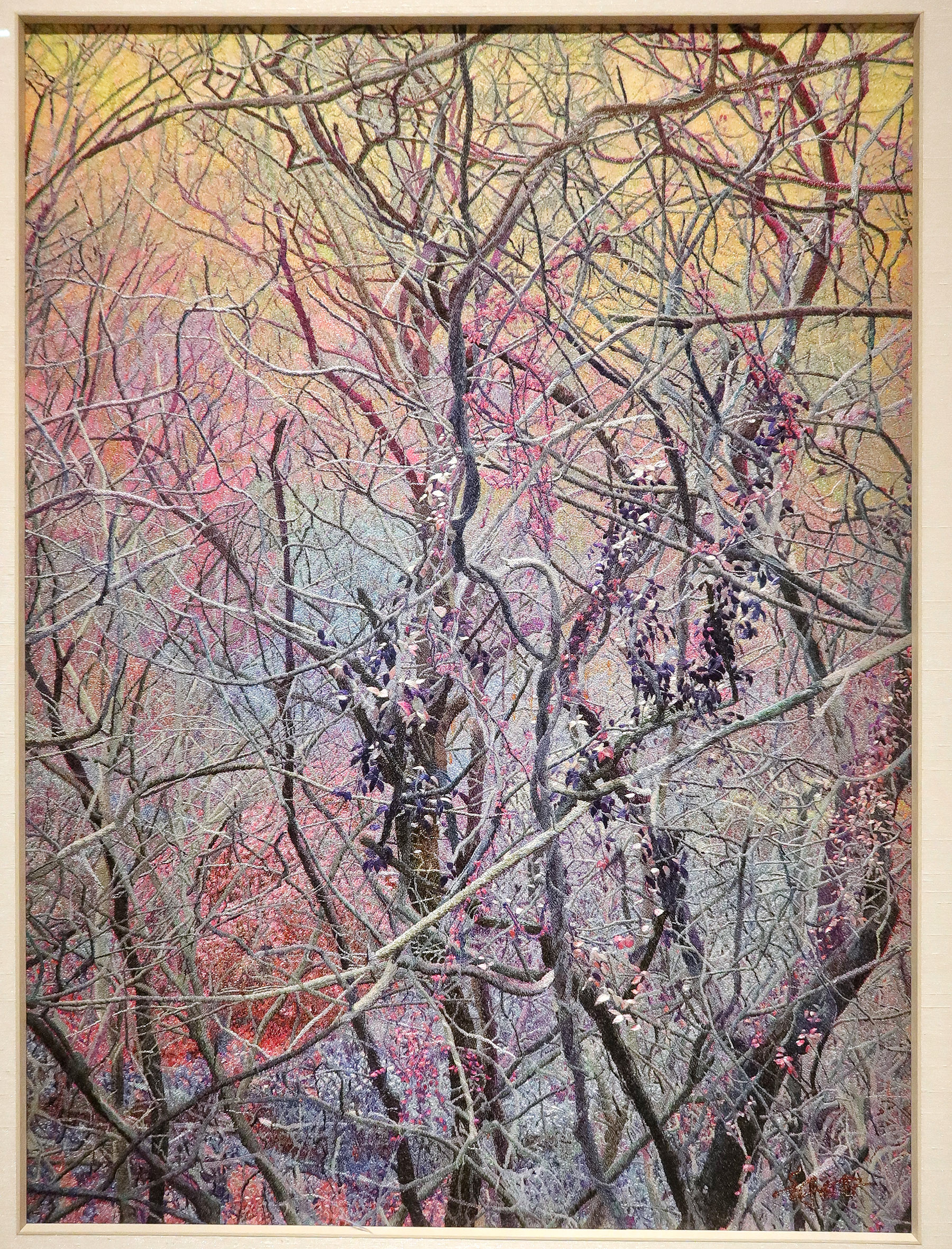

What impresses him most is Zou's four-piece set, Chanrao (entanglement), with one housed in the collection of the British Museum and another on display at the exhibition. Inspired by her photographs of bare winter branches, Zou translated them into vibrant, tangled webs of color using the didi stitch.

"Each vine is like humanity, needing mutual care," she interprets. "An interdependent entanglement, just as we depend on Earth."

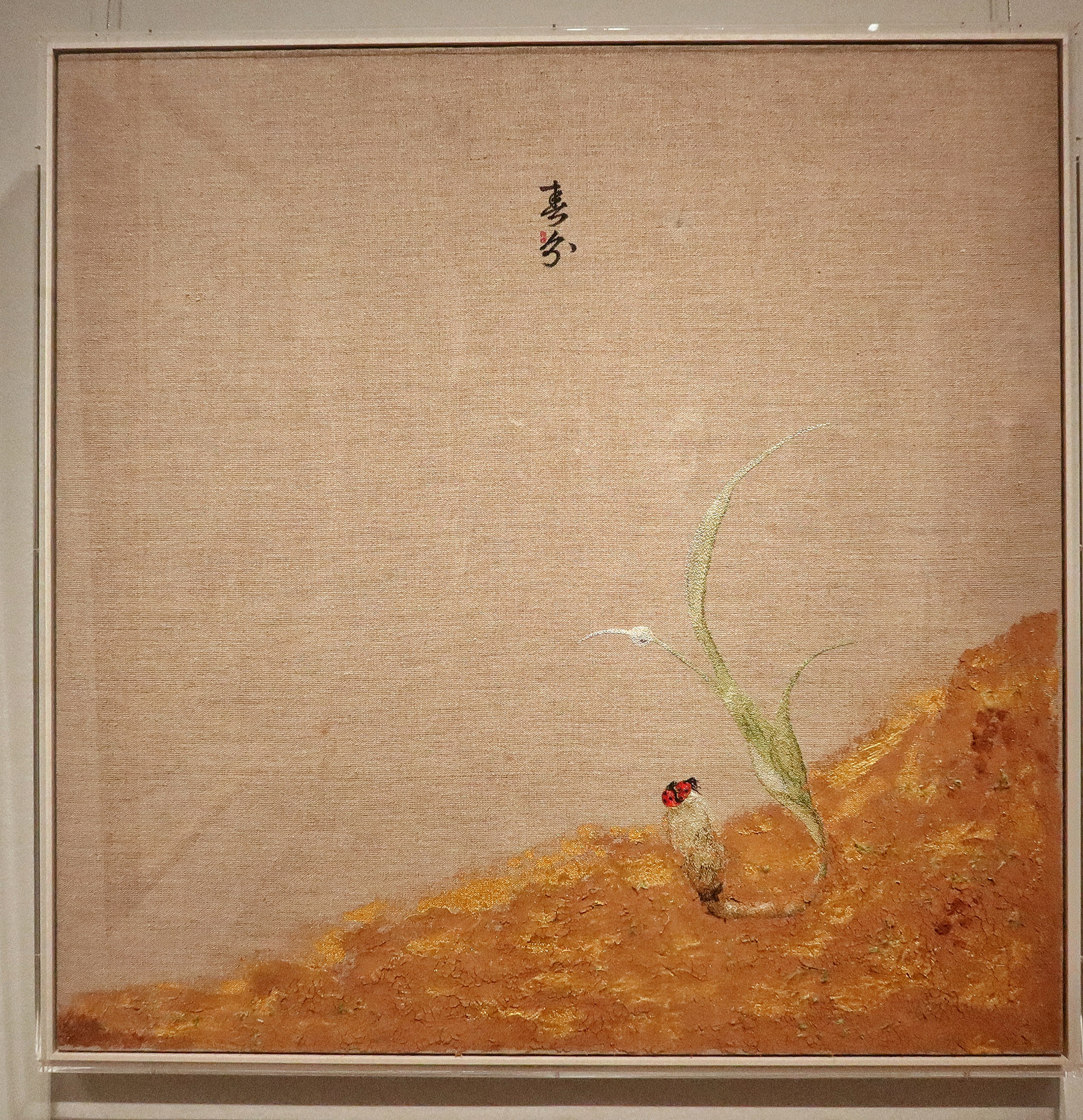

Another piece, which aims to raise public awareness of the environment, is Chun Fen (Spring Equinox), featuring real, cracked earth mounted on silk. Within the soil, she embedded clipped thread ends and gold dust. A single embroidered seed sprouts from the textured surface, accompanied by two tiny ladybugs — a tribute to agrarian life, renewal, and scientist Yuan Longping, known as the father of hybrid rice.

"I wanted to stitch upon the earth itself to make people feel that embroidery can connect with the soil," she says. The piece helps break the stereotype about Su embroidery as a rarefied, untouchable art.

In addition to innovation, Zou devoted years of her life to resurrecting the pizhen stitch (split needle stitch), a technique once vital to Silk Road textiles but lost to time.

"I was young and could still travel, so I took my needle and thread and learned from the ancients all over again," she says. Her mission was to "bring it back to life and tell its story".

That story finds its most profound voice in Sekong Bu'er (emptiness is form), a rendering of Guanyin (the Bodhisattva of Mercy) mural at the Dunhuang Mogao Caves in Gansu province, known widely for its beautifulness and elegance.

Using the split needle stitch and the didi stitch, she spent three years in dialogue with long-ago embroiderers. She rotated individual silk filaments to catch the light, making the bodhisattva's serene expression and flowing robes shift with a viewer's movements.

If Zou's innovation is in depth and technique, the question of breadth — how this rarefied art connects with a new, broader public — finds its answer in the generation watching from beside her frame. Her son, Zou Yuanhan, grew up with the whisper of silk being drawn through linen.

"My grandmother embroidered kittens and goldfish. My mother began to develop her own expression," Zou Yuanhan, 28, says. "I watched her spend years re-creating a lost piece for Dunhuang. That left a deep mark. It wasn't just a craft; it was a cultural act."

This legacy is both an inspiration and a challenge to reinterpret. Zou Yuanhan's initial forays were straightforward: licensing traditional Suzhou patterns to international brands for socks and apparel. "It wasn't very successful," he admits.

The breakthrough came from reimagining the context, not just the product. He transformed part of the family's studio in Suzhou into a cafe, pairing tea and coffee with embroidery displays and hands-on workshops. The goal is disarmingly simple: to make the craft accessible.

"We want people to touch it and try it," he says. He and his mother have developed beginner-friendly kits — tiny, predesigned patterns of a fish or a flower that can be finished in an afternoon and turned into a card, a pendant, or a sachet.

"It's about returning embroidery to all aspects of life," he says. "My mother's work shows, at its peak, as high art. We also need to show its potential as a daily pleasure."

His collaborative piece with his mother, inspired by a trip along the Maritime Silk Road, uses a single, recurring motif of a water droplet. "Water is a theme we cannot avoid," he says. "It's a small starting point for my own expression."

ALSO READ: Threading together culture and modernity

This modest, contemporary symbol, rendered in his mother's exquisite stitches, represents a new kind of dialogue across generations.

In a rapidly developing society, Zou Yingzi has ensured the ancient craft retains its profound voice. Her son and a new cohort of innovators are now tasked with amplifying it to ensure that the conversation she started with ancient needlework finds eager listeners in crowded cafes and on digital screens, inviting a new generation to pick up a needle and add their own thread to the story.

Contact the writer at wangqian@chinadaily.com.cn