In the second installment of her series pegged on the growing market share of women artists the world over, Chitralekha Basu finds out how the women artists of Hong Kong navigate the art market and sustain themselves.

In 2003, Jaffa Lam (1973-) presented four installation pieces at a Hong Kong exhibition called murmur. Made out of recycled crate, carpet and rice paper, Lam’s offerings made for a tender memorial to the collective suffering and anxiety experienced by Hong Kong people during the SARS epidemic. The show also marked the arrival of an artist with a community-engaged practice that involves the participation of manual workers such as carpenters and seamstresses. A number of Lam’s works feature spectacular patchwork canopies, stitched together by the seamstresses of the Hong Kong Women Workers’ Association — drawing attention to fabric waste and the role of industrial labor in the textile industry.

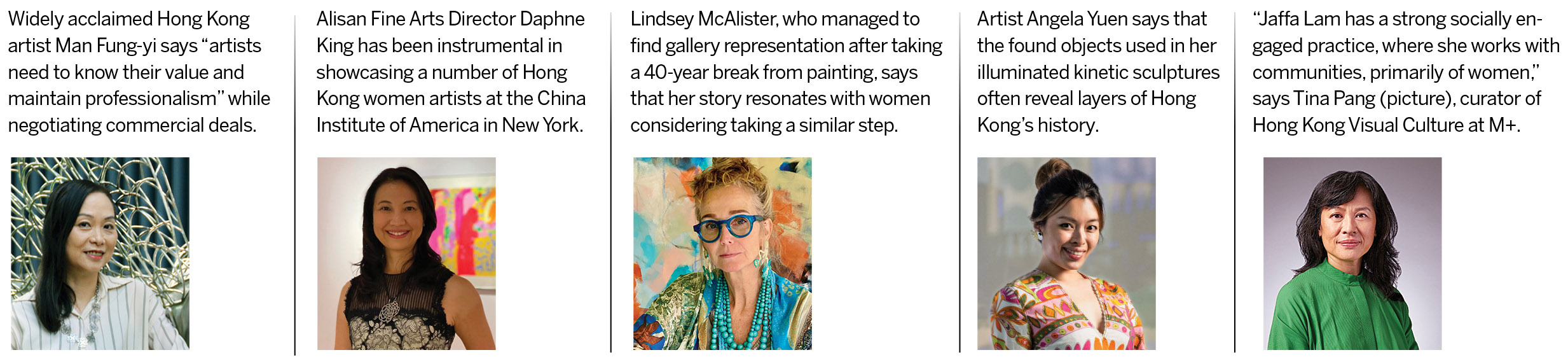

“Lam connects different sorts of histories, including the history of sculpture in Hong Kong. She also has a very strong, socially-engaged practice where she works with communities, primarily of women,” says Tina Pang, curator of Hong Kong Visual Culture at M+. The museum collected at least two pieces by the artist, who is also featured in The City Collection, Antwerp, and Centre Pompidou in Paris.

READ MORE: Drawing attention

And yet, for a long time Lam struggled with finding a home for her artworks. And even now, having been a part of the conversation on Hong Kong contemporary art for at least two decades, Lam says that “the situation hasn’t fundamentally changed” when it comes to marketing her work. “My large-scale sculptures and installations remain difficult to place with either institutions or private collectors,” she says.

In her case, size probably matters, for her signature expansive recycled-fabric patchwork pieces can be 14 meters long, as was the one in her Art Basel Hong Kong 2023 installation, Trolley Party.

Thanks to the endorsement by globally influential museums and “the dedicated efforts of Axel Vervoordt Gallery, which has represented me for the past four years”, today Lam has the attention of a relatively larger clientele.

“Yet the reality is that pieces of this ambition and size still require exceptional commitment from the buyer and often significant logistical and financial support that goes far beyond what is needed for a standard acquisition.”

While she also makes the odd “small-to-medium-scale works that have found homes with individual collectors”, Lam insists that she would never “intentionally downsize my practice to make pieces that are easier to sell”.

“I continue to create at the scale that feels authentic and necessary to the idea, follow the work where it wants to go.”

Backing of galleries

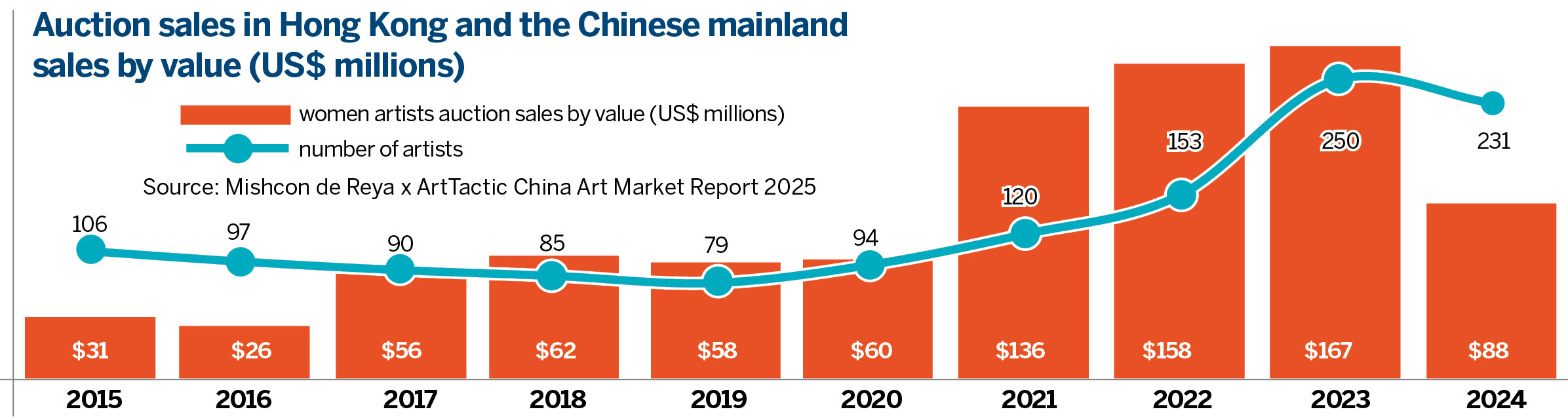

According to “The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2025”, the share of works by women artists in the primary market, i.e., art galleries, rose from 36 percent in 2018 to 46 percent in 2024. However, for a number of Hong Kong art galleries — irrespective of whether they are women-led, which most of them are — highlighting and foregrounding the achievements of women artists of the city has been part of a consciously adopted agenda for years.

Soon after taking charge of Alisan Fine Arts in the early 2010s, Daphne King was concerned about the “lack of female representation in the art world”. “Trying to balance the narrative” has been a priority ever since. The gallery has hosted a series of women-artists-only group shows, including Women + Ink in 2019, and Hope, a fundraiser celebrating the works of outstanding contemporary Chinese women artists the year before. The artists ranged from Fang Zhaoling (1914-2006) — who evolved a unique visual language in her modernist interpretations of calligraphy-embellished traditional Chinese ink landscapes — to 1989-born Cherie Cheuk, who brings a youthful joie de vivre to her ink paintings by inserting contemporary cultural elements such as Rubik’s cubes and Pac-Man icons.

Since the opening of its base in New York City in 2023, the gallery has exhibited Hong Kong artists Irene Chou (1924-2011), Fiona Wong (1964-), Man Fung-yi (1968-) and Bouie Choi (1987-) at the China Institute in America. Also on the gallery’s roster, and poised to make her mark overseas is Angel Hui (1990-), who, together with fellow conceptual artist Kingsley Ng, will represent Hong Kong at a Venice Biennale 2026 collateral event.

King has closely watched Hui’s growth as an artist since the time the latter was a student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, from where she took her masters’ degree in experimental art in 2017. The director of Alisan notes with delight how Hui’s practice has gone from strength to strength over the years. Starting off with realizing the exquisite blue cursive floral patterns of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) underglazed porcelain on unlikely surfaces such as tissue paper and crushed soda cans, today Hui is creating massive immersive installations.

“As Hui’s practice evolves, her reservoir of cultural motifs and techniques has grown and her art has become more immersive and impactful,” says King, referring to Hui’s interactive site-specific installation, Angel Pop Up Store, displayed at Fine Art Asia in 2024. “The artist brings the iconic dai pai dong — Cantonese fast-food restaurants with al fresco seating — street culture into the exhibition hall, inviting viewers to sit down and interact with the artwork.”

Career reinvention

There will always be more artists out there than Hong Kong’s art galleries can possibly take on, and it doesn’t get any easier if you’re a late bloomer. It’s “a crowded, competitive market that is historically not always kind to ‘older’ women artists, but I actually find that quite energizing,” says Lindsey McAlister (1960-). A familiar face in the city’s cultural circles, McAlister founded the Hong Kong Youth Arts Foundation in 1993 and has nurtured generations of young theater aspirants.

She revived her painting practice in 2024 after a 40-year hiatus. Since then her abstract works, replete with bold, assured marks in vivid colors, slapped on to the canvas with evident rhythmic energy, have found representation with two Hong Kong galleries — Kambal and The Spectacle Group. McAlister made it to the Affordable Art Fair 2024 and Art Central in 2025, and has been exhibited in London and Manila, besides various venues in Hong Kong.

While the digital prints of her artworks seem to have found a steady market, through online platforms, “the painting has been slower to gain traction commercially”.

“But the reception has been warm,” says the artist. “People seem curious about the journey itself: the idea that someone can step away from painting for four decades and come back with fresh eyes and a sprinkle of fearlessness. That narrative seems to resonate, especially with women who are thinking about their own creative reinventions.”

Jaime Lau, director of The Spectacle Group, says she offered representation to an older new artist because “Lindsey has a creative energy that is hard to ignore”. Moreover, Lau says, McAlister’s art resonates with a wide demographic. “Even though she’s new to the visual-art market, her paintings have an immediacy and confidence that people feel at first glance. She works with joy, spontaneity and a certain fearlessness. Collectors have connected with her sincerity and bold palette, and her shows have attracted both seasoned buyers and younger audiences. For me, that’s a strong sign of lasting potential.”

Co-branding and merch

A number of Hong Kong women artists have done the odd commercial gig, whether as a side hustle, or for the sake of greater exposure or simply to try out something new. McAlister uses print-on-demand platforms to market her Hong Kong-themed designs on flasks, tote bags and tablecloths under the brand name Crafty Bitch. The enterprise is “more about visibility and fun than a serious income stream”, she says.

Angela Yuen (1991-), whose mesmerizing slow-rotating kinetic sculptures are collected by high-profile institutions in Hong Kong and overseas, was invited to design the scenography for a special display to celebrate Hermès’ petit h materials store in Paris at the lifestyle brand’s outlet in Hong Kong’s Landmark. Yuen’s signature style involves the use of found objects, fabric scraps, scale models and generic Hong Kong miniature plastic toys. Using these tiny discarded and forgotten things and a manipulation of light sources, she manages to magically conjure up silhouettes of familiar Hong Kong landmarks on the wall. For the Hermès commission, she visited petit h’s materials store in Paris to “collect buckles, hinges, and saddle parts, and recomposed them into a suspended light installation”.

“When illuminated, these fragments cast shadows that reveal Hermès objects — like chairs or bags — in their ‘final’ form. It became a way of visually unfolding the brand’s history, just as my practice often unfolds Hong Kong’s past through found materials,” Yuen says, adding, “Hermès granted me complete artistic freedom, which made the collaboration feel like an artistic dialogue.”

Man Fung-yi, who had tied up with the fashion brand Louis Vuitton for showcasing her metallic-thread cheongsam sculptures in Taipei, Hong Kong and Singapore, is all praise for the brand’s respectful approach, and that the commission was inspired by “a genuine love for artistic development”.

Her advice to younger artists is that “they do not need to agree to all the commercial deals” offered to them and would do well to “look closely at the terms” before they sign on the dotted line — make sure that “the brand is being fair and respectful toward them”.

“Artists need to know their value and, most importantly, maintain professionalism,” she adds.

Artist as academic

Many Hong Kong women artists hold academic positions that ensure a steady income. Man used to be a senior instructor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) for many years and now lectures part-time. Hui is an associate professor at the Academy of Visual Arts at Hong Kong Baptist University. Lam was academic head at the Hong Kong Art School until recently and now teaches part time at CUHK.

Getting to share ideas about art with young people can provide a nonmonetary, but nonetheless vital, kind of sustenance.

On Nov 27, the day after the Wong Fuk Court fire had claimed 160 lives, Lam and her CUHK students could see the smoke still rising through their classroom window. The class turned into a freewheeling conversation “about disaster and art, about what an artist’s role might be — or should be — in moments like these”.

“Sharing honest perspectives with my students became another way to express grief and solidarity,” says Lam. “I feel fortunate that besides being an artist; I am also an educator, a neighbor, and a fellow citizen. These roles allow me to respond to a disaster in ways that feel quieter, slower, and more human than making an object ever could.”