In the first essay of a series on how women artists — a historically underrepresented and undervalued group in the art world — of Hong Kong are claiming a seat at the table, Chitralekha Basu looks at the long-overdue growth of their market share and how women collectors are throwing their weight behind the cause.

If you are a collector who hasn’t been to Hong Kong since the COVID-19 pandemic, brace up for a few surprises once you touch down on the city. Not only have the big three global auction leaders — Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips — moved their respective Asia headquarters to sprawling, multifloor, state-of-the-art facilities; the auctioneers in charge there are, increasingly, women, and some are only in their late 20s. From Georgina Hilton who heads up Classic Art, Asia Pacific at Christie’s, to CC Wang, head of business development, Greater China at Sotheby’s Asia, to Danielle So, Hong Kong head of auctions, Modern and Contemporary Art at Phillips, it’s these promising young women who are calling the shots on the floor.

READ MORE: Making it count

Their growing, and assured presence at Hong Kong’s auctions is emblematic of a paradigm shift in the city’s art ecosystem. Even as the art market, the world over, continues to slide since the postpandemic boom in 2021, the market share of women artists — a number of them from Asia, and China in particular — continues to rise.

According to the “Mishcon de Reya x ArtTactic China Art Market Report 2025”, published in March, the number of women artists featured in auctions held on Chinese soil “has almost tripled, rising from 79 in 2019 to 231 in 2024”, with 201 of them represented in Hong Kong auctions. And though a disproportionate 62 percent (valued at $54.5 million) of this market is claimed by the Japanese godmother of conceptual art, 96-year-old Yayoi Kusama, Chinese women pioneers of modernism, Pan Yuliang (1895-1977) and Lalan (1921-95), as well as Chen Ke (b. 1987) — a Beijing-based contemporary artist known for her idealized portraits based on photos of the female students during the Bauhaus era (1919-25) in Weimar, Germany — have made it to the roster of global top 10 women artists in terms of sales.

September saw Hong Kong-born artist Firenze Lai’s (1984) work on paper, Basic Knot (2016), fetching HK$477,300 ($61,340), way above its highest estimated price, at a Phillips evening sale in the city. Phillips’ So confirms that the auction house’s recent success with Lai, Elaine Chiu (1996) and Kristy M Chan (1997) has inspired it to actively seek out and promote more women artists from Hong Kong in local and overseas markets.

“Highlighting Hong Kong women artists remains a key priority for our future plans,” So says. “Our strategy is to continue integrating their work into our international auctions and curated selling exhibitions, ensuring they are presented alongside their global peers. We have seen strong market success with artists like Lai, Chiu, and Chan, which confirms a growing collector appetite. Building on this momentum, we are actively seeking new opportunities to showcase these important local voices.”

Asian women artists rule

The trend of collectors leaning toward women artists is conspicuous across Asia and particularly in Hong Kong, says Ada Tsui, department head of 20th/21st Century Art at Christie’s Asia Pacific. “Season-on-season, we see results for women artists on the rise,” she adds, citing the fact that three of the top five works by Indonesian abstract expressionist painter Christine Ay Tjoe (1973) were sold at Christie’s Hong Kong over the last five years.

If the new, enhanced interest in works by women — a historically undervalued and underrepresented group that still constitutes only 9 percent of the global auction market — is down to, as Tsui says, improved “exposure and education”, paradoxically enough it was the enforced isolation during the pandemic that helped catalyze it.

“The pandemic accelerated our relationship with art online — it was an opportunity to explore and discover new artists from all over the world through virtual exhibitions and social media content. It is likely that this online shift had an influence and undoubtedly continues to do so,” Tsui says, hastening to add that museums, art galleries and other cultural organizations in Hong Kong, and indeed across Asia, have also played impactful roles by “upping their inclusion of women artists, and this is building profiles and underscoring their importance”.

Women supporting women

Published in October, “The Art Basel and UBS Survey of Global Collecting 2025”, authored by Clare McAndrew, states that women collectors spent 46 percent more than men on art and antiques in 2024. Even more reassuringly, women collectors have demonstrated a preference for works by fellow women. The same survey reveals that high-net-worth women collectors spending upwards of $10 million in 2024 spent 49 percent of their art investment on works by women, while men dedicated only 40 percent of their collection to women artists. In Hong Kong, the gender gap is slightly less pronounced, with male collectors spending 41 percent on works by women in 2024-25, as opposed to 47 percent by women collectors.

Tsui offers two main reasons why women collectors are “making a concerted choice” to pick up works by fellow women. “This can be down to feeling a personal resonance and connection with the works. It can also be about advocacy — to support and cultivate the market for women artists.”

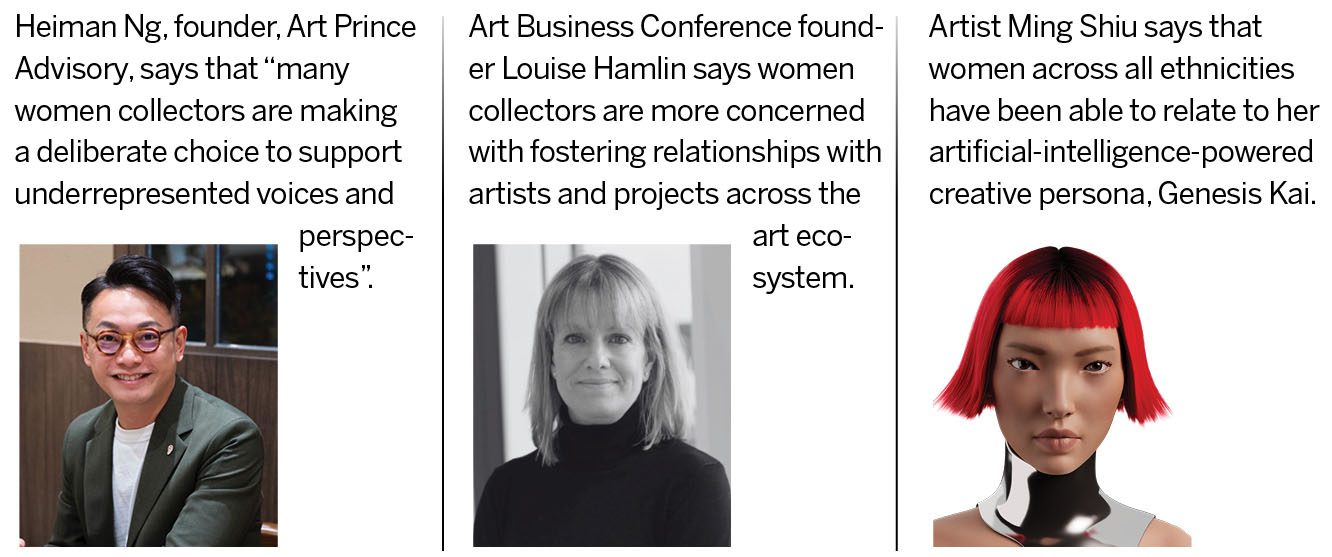

Heiman Ng, founder-director of Art Prince Advisory, agrees. “Many women collectors are consciously supporting and championing female artists. This goes beyond mere preference; it’s a deliberate choice to support underrepresented voices and perspectives.” He cites the example of Hong Kong oncologist Dr Patricia Poon, who is exclusively into collecting works by the city’s women artists, extending her support by promoting the works she picks up through her social media channels. Her Instagram account is overflowing with snapshots of works by Hong Kong women artists, such as Angel Hui (1990), who is known for adapting traditional Chinese blue pottery designs in the forms of soft-drink cans and handbags.

Buying for the family

Both Angelle Siyang-le, director of the city’s flagship annual international art fair, Art Basel Hong Kong, and Carola Wiese, senior adviser, UBS Family Advisory, Art and Collecting, agree that women collectors being partial to women artists might be a trend that’s more pronounced in Hong Kong than elsewhere. And both draw attention to how women collectors tend to turn the act of buying into a family affair, often buying toward augmenting a family collection, bringing along, as Wiese says, young adult children to share the experience. That’s when “the collection becomes a family endeavor and actively contributes to family unity”, says Weise. “It also serves as a time window for sharing the joy of collecting together between generations, especially when done by a mother daughter duo.”

The idea of buying art as a collective experience — in which artist, gallery owner, art fair organizer, art adviser, collector, and their mother, participate — resonates with most women collectors. Tsui’s description of the network involving women collectors and the team of talented women specialists she leads at Christie’s in Hong Kong sounds like a sisterhood of women connecting over art. The activities and ideas shared between them “really helps to build affinity with our female clients, and particularly with the new generations of millennial and Gen-Z female collectors”, she adds.

Open to adventure

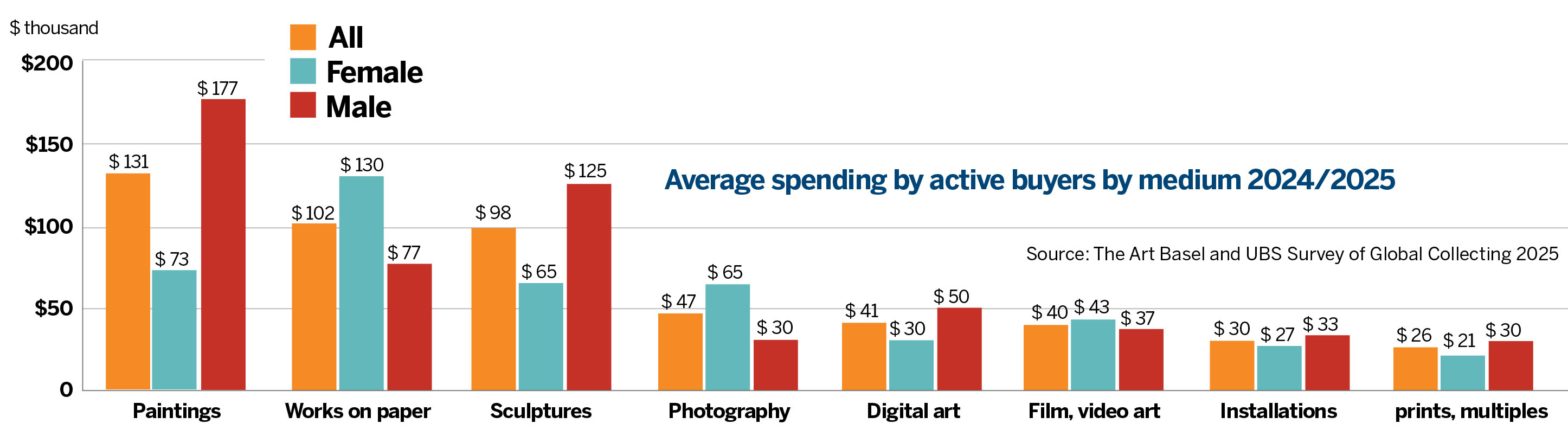

The Art Basel and UBS survey also highlights women collectors’ fondness for slightly off-beat categories. Women collectors report a larger share (16 percent) of spending on digital art compared with men (13 percent), photography (women spent 11 percent, men 8 percent); works on paper (women spent 10 percent; men 9 percent); installations (women spent 7 percent; men 6 percent).

Among the 3,100 high-net-worth individuals — of which 37 percent were women — surveyed across 10 key art markets of the world, women collectors outdid their male counterparts by patronizing the marginalized categories, such as works on paper ($130,000 spent by women, $77,000 spent by men); photography ($65,000 spent by women, $30,000 by men); film and video art ($43,000 by women, $37,000 by men).

“In my experience, women collectors are less concerned with trophy collecting but rather with fostering deeper relationships and new concepts of patronage with artists and projects across the art ecosystem, which ultimately support more grassroots artists and other mediums including digital art and photography,” says Louise Hamlin, founder of the global brand Art Business Conference. Its maiden event in Hong Kong was held in November.

Widely acknowledged as a pioneer of digital and video art in Hong Kong, Ellen Pau (1961) points out that women collectors’ preference for moving-image artworks has to do with women’s natural affinity to sharing of stories in intimate environments.

“Digital and video artworks often offer more direct personal engagement, flexible modes of display, and a sense of immediacy that resonates with collectors who value narrative, intimacy, and experimentation,” she says, pointing out that “the digital realm tends to feel more open and less restricted by traditional hierarchies, which can make women collectors more willing to explore it”.

The fact that a huge number of contemporary women artists, from Hong Kong especially, “are strongly represented in these mediums” acts as an incentive for women collectors, as a number of them strongly believe in “supporting innovative practices and more inclusive artistic voices”, Pau adds.

Collecting the future

Hong Kong was at the forefront of the nonfungible token (NFT) art market boom in 2021. Though that field of art trading has been mired in controversies since then, Jaime Lau, founder-director of The Spectacle Group, a gallery with a number of women NFT-art makers, such as Harriet Hunter, on its rolls, says that women collectors continue to patronize the art form, often because they are interested in the maker and their processes.

“Women collectors respond to works that explore identity, emotion and personal transformation in pieces where meaning comes before mechanics. When the story behind the artwork resonates with their own experiences and values, the engagement becomes far stronger than anything driven by rarity or speculation alone,” she says.

NFTs are often sold together with their physical iterations, and Lau says that women collectors are “very interested” in such “hybrid art”. “They’re also generally excited about the fact that NFTs are the type of art that you could bring along anywhere to play with, especially true of our NFTs which have built-in augmented-reality function.”

Women collectors seem equally interested in the possibilities that artificial-intelligence-powered art has to offer. “Women across all ethnicities have connected with me as Genesis Kai,” says Ming Shiu (1998) of her AI-generated avatar. “They see her not as just a persona but as a kind of philosophical daughter, an imagined lineage of heritage, yearning, and self-invention. Women tend to read the emotional infrastructure of the work before they read the medium,” says the artist of Hong Kong and South Korean descent, represented by Hong Kong gallery Ora-Ora.

“Women don’t just view my work; they inherit it.”