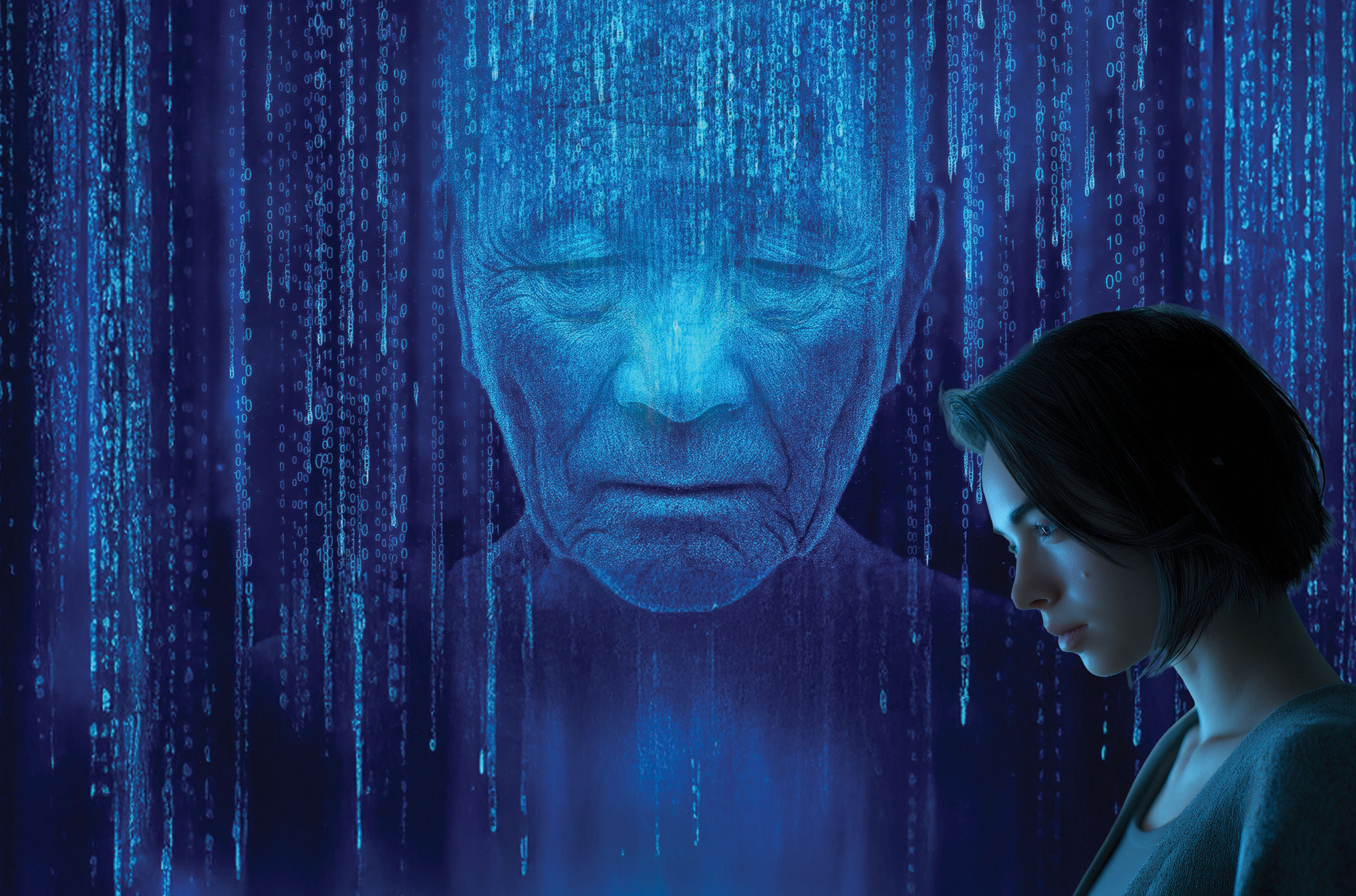

“Superbrain” technology providers can now create digital agents, enabling people to “video chat” with their deceased loved ones as in real life. But, as Wu Kunling reports, “resurrecting” the dead could trample on legal, social and privacy matters and needs to be regulated before the technology reaches broad commercial use.

Editor’s note: Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing our daily lives and the ways we forge connections, transcending the barriers of time and space. The second article in this AI series delves into the emerging field of “digital immortality”, where AI preserves life’s essence beyond loss.

Three years after her father died, 47-year-old Zhang Xinyu heard his “voice” again, responding to the “I love you” she had finally had the chance to say. The response came from a digital agent via her cellphone.

Powered by cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence, the agent recreates her father’s voice, appearance and speech patterns. Every evening, Zhang and her father would “video chat”, enabling her to share her daily ups and downs, and her father would “respond” with warmth and understanding.

“I feel like dad’s still here, accompanying me as I get older,” she says. It was only then she realized how hard-won peace and happiness have been.

Zhang’s father died of cancer in late 2021, leaving her to grieve during the following years. Despite resorting to various methods like meditation and charity work, she couldn’t erase the pain until she found a service that can “clone” the deceased using digital technology — a recent breakthrough in human-computer interaction.

After carefully comparing different providers, in May Zhang decided to give it a try.

She supplied the company with her dad’s photos, audio clips and written memories. To make the replica more genuine as in life, she described his speech habits and facial expressions. After two versions were made, she was happy with the results.

Zhang vividly recalls her first conversation with the agent. Hearing her father’s “voice” and seeing him “smile” again made her feel empowered instantly. Although her mother and friends worry she could become too addicted, the “companionship” renewed her confidence in life.

“It’s like I’ve rebuilt my home — a home with dad, mom and myself,” Zhang says. To her, it isn’t escaping from reality. Instead, while preserving old memories of her father, the digital agent can create new beautiful moments, healing regrets she has harbored since her father’s demise.

Zhang envisions more advanced technologies on the horizon that would bring her closer to her father, and she says she would try out whatever comes next. “I’ll witness it together with my digital dad.”

Digital immortality

The digital replicas of Zhang’s father were created by Superbrain Studio — a startup based in Nanjing, Jiangsu province — that has been making such tools since 2023. Zhang Zewei, who founded the enterprise, calls the service “digital immortality”.

As one of China’s earliest players in the niche field, the studio has fulfilled over 20,000 orders, having captured roughly 30 percent of the domestic market as of June this year.

To put it simply, the service involves utilizing AI and other technologies to replicate a person across different dimensions like his or her voice, appearance and mentality, creating a digital agent capable of reacting in real time, mainly through video chats. These agents can operate online using devices like cellphones and computers, offline, or as holograms, depending on a client’s preference. The cost for the most basic service is approximately 2,000 yuan ($283), followed by an annual maintenance fee of around 300 yuan.

Beyond individual orders, Superbrain Studio has teamed up with privately-run cemeteries, allowing visitors to scan the QR (quick response) codes on tombstones to interact with digital replicas of the deceased.

Some clients also customize services for commercial use. Knowledge influencers use these agents as “avatars” to provide paid consultations. But, most clients prefer creating digital replicas to remember their departed loved ones and relatives, according to Zhang Zewei.

He says there is also a trend involving creating agents for the living, sometimes, for clients themselves. One client, a terminally-ill cancer patient, commissioned a digital clone of herself, hoping it would accompany her children after she’s gone.

The trend emerged late last year, coinciding with the much-heralded rise of Chinese AI model, DeepSeek. The entrepreneur believes DeepSeek’s popularity provided a foundational AI education for many and introduced more people to his industry.

Technology — merely a tool

Despite the industry’s rapid growth, Zhang Zewei describes it as “a business ahead of the law”. With limited regulations to follow, his studio is highly cautious when accepting orders. He tells clients to sign legal documents to prevent such services from being misused for illicit activities. These include authorization for using relevant data like portraits and voices, whether for themselves or relatives, as well as death certificates and proof of kinship with the deceased.

They also need to pass thorough background checks and psychological well-being evaluations, with standards drawn from accumulated experiences, as well as guidance from experts in law, psychology and sociology.

Zhang Zewei recalls that, on one occasion, his company rejected a Shanghai mother’s request to clone her deceased daughter due to her fragile mental state and an earlier attempt to commit suicide. He explains that granting the woman’s request would risk exacerbating her grief, noting that the business is service-oriented, with technology merely used as a tool.

Replicating a person’s appearance and voice is no hurdle with today’s technology as it needs just a single photo and a six-second audio clip in some cases. By 2025, most clients are satisfied with the realism in these aspects, says Zhang Zewei. The real challenge and the core of “digital immortality” is replicating a person’s thoughts and consciousness — a process he likens to “constructing a philosophical system”.

To achieve this, detailed recollections, ideally diaries or memoirs would be provided by clients for large language models to absorb. Specialists would also mimic a person’s thinking patterns by extensively questioning his or her views on various topics. By leveraging detailed memories and associated reasoning styles, the team would embody the person’s inner world into the agent.

Before delivery, the agent would need to undergo a Turing test-like evaluation, during which humans judge whether the machine’s responses are indistinguishable from a human’s. The test is carried out jointly by the team and the client to verify whether the machine’s responses are in line with customers’ expectations.

According to Zhang Zewei, more than 90 percent of his clients find the mental replication convincing. At this point, the clone is practically complete, while it can also be continuous in post-delivery operations as long as clients supply new material for large language models to learn from.

The process involves collaboration among multidisciplinary professionals, including data organizers, model trainers and specialists to enrich the agent’s voice with emotions, as well as computer vision engineers to help the agent recognize humans and display various micro-expressions, with contributions from experts in psychology, philosophy, and sociology.

Over the past three years, Zhang Zewei says he has observed rapid tech advancements and cost reductions in the industry, predicting it would become a billion-yuan business. His confidence is grounded in technology and fundamental human emotions, emphasizing Confucian values like filial piety in Chinese culture, where death is treated with solemnity.

“To preserve memories, people first used paintings, then black-and-white photos, color photos, videos and panoramas. Today, new technologies allow all these one-way records to evolve into two-way interactions, providing better ways to cherish beautiful memories. Such a demand is far from unconventional,” says Zhang Zewei.

The younger generation, especially those raised in the AI era, will likely be more receptive to such innovative concepts. Coupled with an aging population, he believes that creating digital replicas of departed loved ones will inevitably become common practice in the near future.

Anticipation and concerns

In April, a research article, entitled “AI Afterlife as Digital Legacy: Perceptions, Expectations and Concerns”, was published during the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems of the Association for Computing Machinery — a top global academic meeting on human-computer interaction.

The article suggests that digital agents represent an emerging form of digital legacy, distinct from traditional digital inheritance, such as audio, photos, videos, social media content or password-protected accounts that the article describes as “static”.

“Unlike those static ones, the novel form, with interactive and evolutionary capabilities, can learn or generate new memories based on human input,” said the article’s first author, Lei Ying — a graduate student specializing in human-computer interaction research at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada.

Another author, Ma Shuai — a postdoctoral researcher at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland — said that while commercial services for tailoring these new digital legacies are growing, public discussion remains narrowly focused on the technology and whether people would “resurrect” the dead.

To explore the overlooked perspective of whether the living are willing to be cloned themselves, the team interviewed 18 participants, aged 20 to 69, from 11 different regions across China, including the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, who varied in gender, occupation, education, health status, AI literacy levels and experiences related to the topic.

Some respondents expressed interest in the services, highlighting personalized needs for their clones. For appearance, some older adults wanted their clones to reflect their youthful prime, while others preferred their appearance to be like before they pass away in order to maintain a sense of presence for their families. One mother preferred her clone to be like before her child entered college, a time filled with shared memories.

Preferences for the clone’s functions also varied. Some wanted them to demonstrate professional expertise, while others desired emotional support for partners. There were differing views on whether clones should integrate new knowledge, with some opposing this to maintain control and familiarity.

But, among other participants, concerns arose over unintended emotional impact on loved ones, as poorly simulated agents might harm rather than comfort. Some feared that relying on avatars could delay emotional healing or lead to judgments about one’s respect and nostalgia based on interactions with the agent.

Legal, social and privacy issues were also troubling. Questions emerged about whether digital entities could legally represent individuals, and who would be responsible if rights were infringed upon during interactions.

Agent management also posed risks, such as tampering, data leaks or resale. Some suggested that regulatory bodies, rather than private companies, should oversee agents to avoid issues arising from company closures. Additionally, the destruction of these entities raised questions about aligning with an individual’s wishes and verifying permanent destruction.

The authors suggested that service providers highlight the risks by introducing, for instance, the over-dependence prevention mechanisms. Lei said those who lost their loved ones are emotionally vulnerable and it’s the service provider that should be responsible for mitigating these risks.

Ma urged authorities to establish an oversight framework before the technology reaches wider commercial use, calling for interdisciplinary collaboration to define regulatory boundaries. He also envisions a dedicated regulatory body to be built as “these agents contain highly personal information and emotional weight and should not be treated like ordinary property even when abandoned”.

During the study, Lei noted that some participants, influenced by traditional Chinese beliefs in reincarnation, questioned AI immortality. They felt people shouldn’t disrupt the natural order by seeking digital forms after death.

Lei warned that these technologies could blur the lines between life and death, potentially devaluing real-life companionship.

She called for long-term sociological experiments to track the psychological and societal effects of interacting with digital clones, saying these technologies are “redefining the connection between life and death”.

Contact the writer at amberwu@chinadailyhk.com