History enthusiast records the treasures of the past to give them a wider audience, Yang Yang reports.

On a cold morning in March 2016, Wang Huilian, 36, once again approached the gate where once stood the pagoda of the Jingzhi Temple in Dingzhou, North China's Hebei province.

On the ground, nothing of the ancient temple is left, but underground, the seven-square meter palace still has delicate murals and an architectural structure that showcases the genius of craftspeople during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

Palaces under Buddhist pagoda foundations are used to settle and enshrine relics, texts and various types of utensils.

READ MORE: Interlocking past with present

In 977, treasures, including sariras and more than 700 artifacts crafted from gold, silver, bronze, jade, stone, wood and silk — like gilt-silver reliquaries and Ding kiln masterpieces — from Northern Wei (386-534) to Song dynasties were secretly buried, sealed and stored in the underground palace of the Jingzhi Temple pagoda. It was not until nearly 1,000 years later that they were finally brought to light.

People can see those exquisite artifacts in Dingzhou Museum but few have the chance to see the underground palace.

Wang, an office worker and history enthusiast living in Beijing, 220 kilometers away, had come here many times, always finding the gate locked without a person in sight.

But on that March morning, without much expectation, she saw a middle-aged lady sweeping the ground with a broomstick. Wang did not hesitate to introduce herself and the reason for being there: "I'm an enthusiast of historical sites. I'm here to see the famous underground palace."

The woman ignored her, focusing on her work. Wang did not give up. She started to tell the woman of her previous visits.

"I said, this is the first time I see someone here, so I'm too excited. Sorry if I talk too much, but she replied coldly, 'I'm just a cleaner. I don't have the key to the underground palace. Please leave. I'm going to lock the gate'," Wang says.

Wang still did not want to give up. She continued telling her how many times she had been there, her knowledge about Dingzhou's history, the disappearing pagodas and the great poet Su Shi from the Song Dynasty, who was demoted to Dingzhou's governor in 1093 due to political struggles.

While talking, Wang picked an extra broomstick in the yard and began sweeping the ground together with the woman. "I didn't expect anything, just wanted to share my stories with her."

But when they finished cleaning the yard, the woman asked her to follow her and opened the door leading to the underground palace. In the following years, Wang went to the temple several times, the gate was always locked and she never saw the woman again.

It is one of the most unforgettable experiences that Wang had in the last two decades during her trips to about 10,000 historical sites around the country, one of the many stories in which she changed people's mind with sincerity.

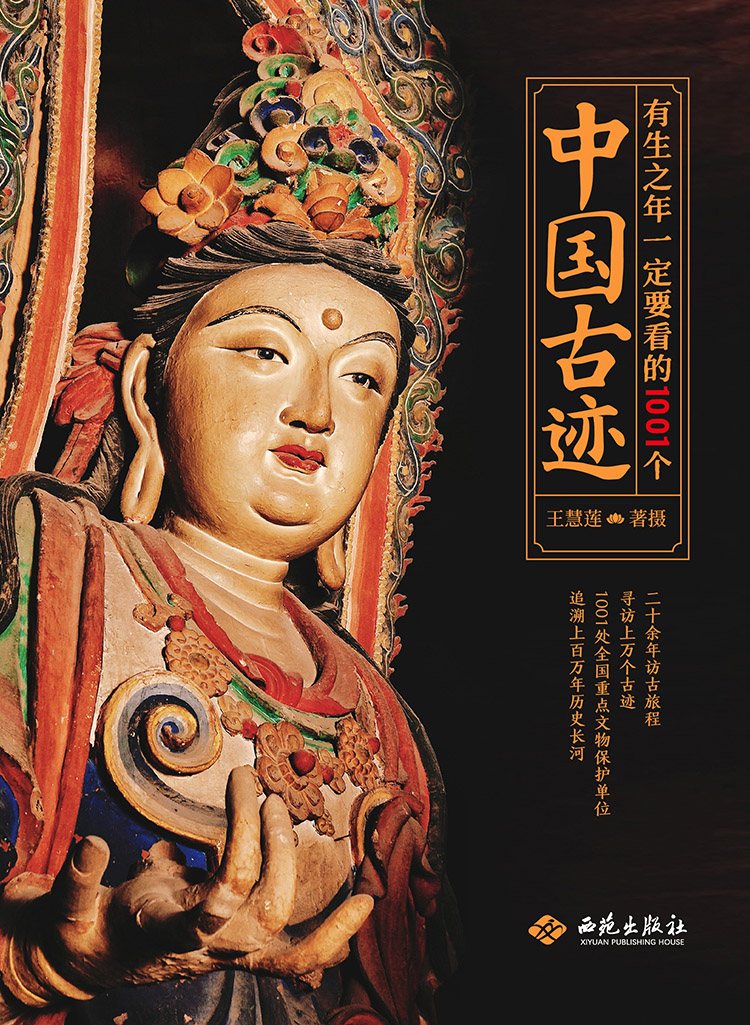

That is how she got the chances to take photos of those historical sites that are not open to the public. Many of the photos are included in Youshengzhinian Yidingyao Kande 1,001 Ge Zhongguo Guji (The 1,001 Chinese Historical Sites You Must See Before You Die), a book by Wang that was published in March.

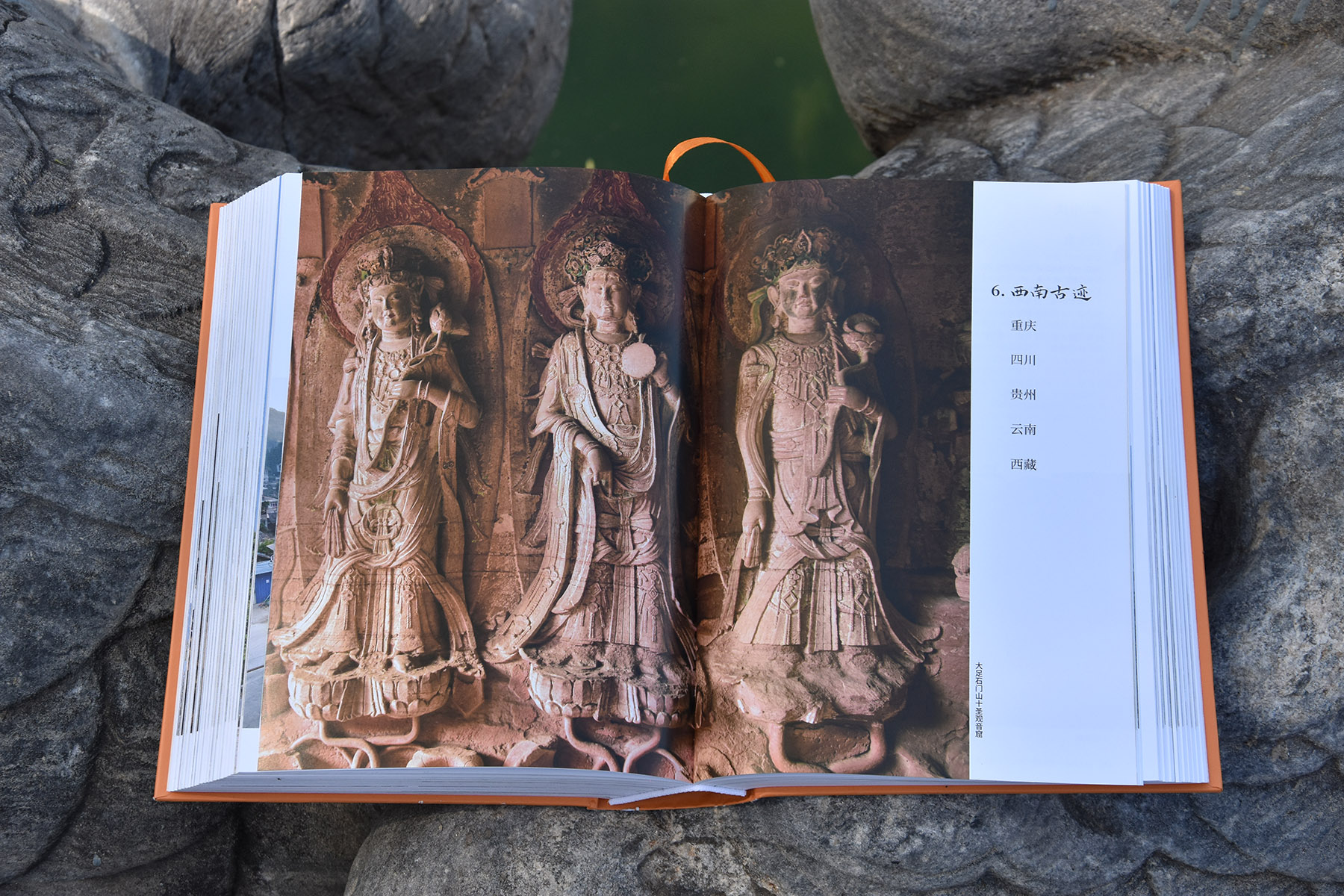

According to geographical location, Wang introduces in the book 1,001 historical sites across the country that are worth a visit on four grounds: historical significance, cultural representatives of various dynasties, aesthetic value, and clues for exploration.

The 960-page book contains a total of nearly 2,000 high-definition photos that record 105 ancient ruins, 119 ancient tombs, 612 ancient buildings and 112 grottoes and rock carvings, all taken by the author.

Historical sites derive significance from their authenticity as temporal witnesses. In the book, readers can find 396 photographs documenting monuments since altered, lost, or reshaped by environment. It also includes rarely documented visuals, seldom presented in digital archives, each reflecting Wang's meticulous effort to immortalize heritage while still possible.

"With rich travel experiences and unique insights, the author provides distinctive interpretations for each historical site," says Shi Manlin, the book's editor with Xiyuan Publishing House.

"Not only does she showcase their external appearance, but also presents their historical stories, cultural significance and social value with professional materials.

"This approach allows readers to feel as if they are traveling through time and personally experiencing the changes that these historical sites have witnessed," Shi says.

"Besides, the book also recommends surrounding historical sites that are not at the national level and can be visited along the way," she adds.

Commenting on the book, Shang Heng, researcher from the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, says that if the 5,058 national key cultural relics protection units are considered the essence of Chinese cultural relics, then the 1,001 selected in this book are the cream of the crop.

Growing up at the foot of the Bell and Drum Towers in Beijing, Wang became interested in cultural relics at a young age. In 2000, when she was a sophomore studying human resources management at university, at a friend's invitation, she went to Qingling village in the capital's Changping district, which sits next to the Ming imperial tombs.

At that time, the Ming imperial tombs were still in disrepair. "Standing in front of the Qingling Stele Pavilion, I was immediately drawn to the broken tiles and ruins, as if I had traveled through time," she says. It was that glimpse of beauty that solidified her passion for history and culture, and inspired her to explore and experience them in the following years.

The first historical sites Wang visited were the wild sections of the Great Wall on Beijing's outskirts — Jiankou, Simatai, Jinshanling and Mutianyu. On the social network platform popular at the start of the 21st century, QQ, Wang found a group of people with similar passion — hiking through the wild sections of the Great Wall.

In free time, carrying a tent, water and some bread, Wang walked 30 km a day. In the evenings, she and the fellow hikers pitched the tents on the Great Wall, watching sunsets and sunrises, enjoying pure happiness.

Gradually, Wang expanded her visit to farther places. In Hebei's Cangzhou, she visited the Iron Lion that was crafted in 953, and saw it before the current shelter was built.

ALSO READ: Towering determination of pagoda chronicler

Visiting historical sites has become an important part of Wang's life that she has been pursuing for more than two decades.

"I love it because I'm always touched by those historical sites that have been standing there for centuries," she says.

"Just imagine all they've endured — centuries of storms, dynastic upheavals, natural erosion, human vandalism, even earthquakes. Yet these ancient structures still stand resilient, radiating timeless beauty to every visitor fortunate enough to encounter them. In their presence, life's worries appear trivial."

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn