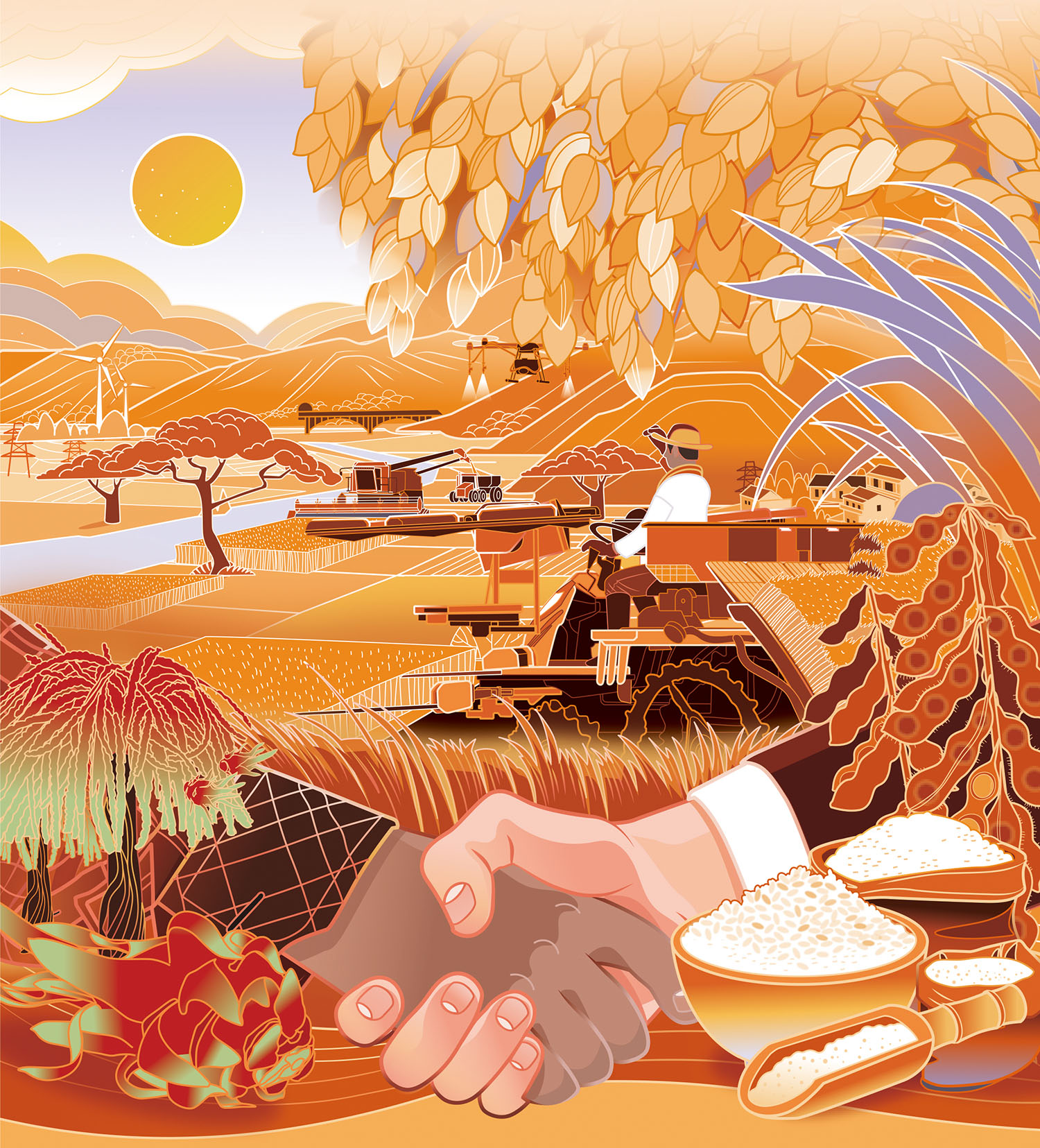

Chinese experts help boost African farm yields with solutions tailored to local needs

When Li Xiaoyun first arrived in Tanzania in the late 1990s as a young student, the arid lands of East Africa, reminiscent of his hometown in Northwest China, sparked a fire within him.

Returning to Tanzania in 2008 as a professor at China Agricultural University (CAU) in Beijing, Li carried lessons from China’s rapid progress in food productivity and compared corn yields between the fertile North China Plain and Tanzania’s struggling fields.

A key difference captured his attention. Chinese farmers were planting more than 60,000 corn plants per hectare, while many of the Tanzanian farmers Li studied settled for about 15,000, resulting in significantly lower yields.

“This was an obvious difference, but many Tanzanian farmers didn’t realize it,” said Li, who is now the honorary dean of CAU’s College of International Development and Global Agriculture due to his contributions to global agricultural exchanges.

Li is part of a group of Chinese agricultural researchers and development experts who have used their expertise to boost food productivity and alleviate extreme poverty in Africa, home to some of the most malnourished people on the planet, in recent decades.

Unlike other previous aid efforts that often called for technologies beyond Africa’s development stage, Chinese experts advocated simple, cost-effective, and easy-to-implement techniques.

During his stay in Tanzania over the past decade, Li spearheaded reforms aimed at bettering impoverished communities through improved agricultural practices.

He introduced the concept of “parallel experience”, which advocates tailored solutions that are aligned with Africa’s specific challenges and opportunities.

“Before our arrival, numerous teams from various countries had already provided assistance in Tanzania,” he noted.

“Often, the solutions were not in line with Africa’s development context,” he said.

Li said that previous projects often skipped much-needed basic farming practices, such as dense planting techniques and intercropping, and promoted more costly methods that included irrigation and mechanized farming.

The ambitious projects clashed with the realities on the ground, such as the fact that most Tanzanian farmers could not afford tractors.

The high cost of fuel and maintenance, and the lack of paved roads also made mechanized farming nearly impossible.

Diverging from these impractical suggestions, Li drew inspiration from China’s agricultural traditions such as optimal planting density, organic fertilization, and crop rotation.

His team started teaching dense planting techniques in 2011 to bolster production.

In 2021, with backing from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Li and his team launched the “Small Beans, Big Nutrition” project.

Under the program, farmers are taught to intercrop corn and soybean; and make secondary soybean products such as soy milk and animal feed.

Intercropping enhanced soil fertility. Soy milk offered an affordable protein supplement, diversifying food resources and improving the nutritional health of smallholder farmers. Animal feed processing extended the local agricultural industry chain, Li said.

Currently, more than 100 families are reaping the benefits of the project, the foundation said.

Soy milk shops have opened in two villages linked to the project. Another village has established a small feed processing plant.

Li’s “parallel experience” theory is one example of China’s efforts to enhance African food production through approaches tailored to specific conditions.

Drought-resistant rice is another example of how Chinese agricultural knowledge is helping Africa increase production, protect wetlands, and combat climate change.

In late July, on the outskirts of Zanzibar, Tanzania, two small patches of rice began to turn yellow in the experimental fields, their plants bending under the weight of their heavy grains.

In the nearby comparison patch, the rice plants looked green and were more than 10 days from reaching maturity.

These fields belong to the Zanzibar Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI), and the rice ripening early was WDR73, a drought-resistant variety developed by the Shanghai Agrobiological Gene Center.

While it has not been officially approved in Tanzania yet, its success in Uganda — where it has been endorsed for nationwide use — impressed Salum Faki Hamad, a rice scientist at ZARI.

Hamad reached out to Liu Zaochang, the Africa project manager at the Shanghai center, to initiate the collaboration.

African countries such as Kenya have joined the Convention on Wetlands, which means they cannot increase planting areas at the expense of wetlands, Liu explained.

“In this context, water-saving and drought-resistant rice has become a great solution in the region,” Liu said.

Since the late 1990s, crop scientists, including Luo Lijun at the Shanghai center, have been building a pool of over 200,000 rice gene samples for breeding purposes.

After decades of hybridization research, they successfully developed the drought-resistant rice strain in 2004. With a 40 percent reduction in water usage, the per hectare yield can exceed 11 metric tons.

Since the variety does not need to be grown in flooded fields, it can also reduce emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, and prevent mosquito breeding.

Scientific research achievements related to the WDR73 variety were recognized with the National Science and Technology Progress Award in 2020.

“Data has shown that the variety has curbed methane emissions by at least 70 percent,” Liu said.

As the Belt and Road Initiative progresses, the center in Shanghai has been introducing the variety to partner countries during the past decade.

Liu said it has been grown in rice fields in northern Vietnam, Burundi, and Kenya.

Agricultural research institutes in Iran and the United Arab Emirates have shown great interest in introducing the variety.

Food security and agricultural development are a priority for cooperation between China and Africa.

Following the China-Africa Leaders’ Dialogue in Johannesburg, South Africa, last year, China published the “Plan for China Supporting Africa’s Agricultural Modernization”, adding new momentum to the cooperation.

Li, from China Agricultural University, said China’s assistance to Africa is mutually beneficial.

Through aid programs, “we have gained insights into new crop planting systems, how Africans tackle challenges like water scarcity, fertilizer shortages, and financial constraints, and especially their diverse food sources and methods to obtain more plant-based protein,” he said.

“It helps us reassess ourselves from a global viewpoint and through the African lens,” he added.

At a news conference on Aug 20, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning was asked about recent Chinese media reports of an African student studying agricultural technology in China.

She said that China empathized with the aspirations of the African people to become free of hunger.

China-Africa agricultural cooperation has flourished in recent years, with significant achievements in expert technical assistance and training, transfer of advanced technology, construction of agricultural parks, and promotion of crop planting projects such as hybrid rice and fungi strains, Mao said.

This has greatly enriched the “grain bags” and “grocery baskets” of the African people and promoted African agricultural modernization, she added.