Enhancement of coal-fired power ensures energy security and vital ‘backup’ for China as it pursues green transition

Editor’s note: As protection of the planet’s flora, fauna and resources becomes increasingly important, China Daily is publishing a series of stories to illustrate the country’s commitment to safeguarding the natural world.

China’s rapid renewable energy expansion has stunned the world. Yet, even as this transition accelerates, international critics have focused on the country’s simultaneous increase in coal-fired power capacity. These observers argue that the trend is both logically and economically unsound, a perceived “double-down” on fossil fuels that contradicts global climate goals.

However, leading energy experts argue that this is not a contradiction but a strategic necessity, as the rapid transition to green energy would be impossible without the stability provided by coal. This strategy is rooted in the reality that while renewables like wind and solar are expanding at a record pace, their inherent intermittency requires a massive, reliable backup system to ensure national energy security.

According to industry experts and data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, China’s coal-fired power infrastructure is being transformed into a high-tech “insurance policy” that provides the bedrock of stability required to support the world’s largest and fastest green energy revolution.

At the heart of this strategy is a fundamental evolution in the role of coal. Traditionally, coal was the “baseload” of the Chinese economy, running at maximum capacity to fuel the nation’s rapid industrialization. Today, that role is being redefined.

Wang Zhixuan, a professor from North China Electric Power University, said that the role of coal in China has fundamentally shifted from being the primary source of daily power to serving as a flexible “safety net” for the grid.

This coal-fired power “backup” enables the country to pursue its low-carbon transition without compromising energy security.

He highlighted the rapid expansion of China’s power generation capacity since the 1990s, a trend propelled by the nation’s swift industrialization and the global shift of industries from the developed world.

“In the 1990s, China’s per capita installed capacity was so low that it was equivalent to powering a mere two light bulbs per person,” Wang said.

According to official figures, China’s per capita installed power capacity was only about 0.24 kilowatts in 1999. As of the end of 2024, however, that figure had surged to 2.5 kilowatts.

This dramatic growth has accompanied an industrial journey that China has traversed in mere decades, but which took developed nations a century or two, Wang said.

The rapid GDP growth and historic improvements in living standards since China’s reform and opening-up from the late 1970s have inevitably required large-scale energy support. This pattern is consistent with industrialization in developed countries.

What distinguishes China’s experience, Wang said, is that its energy consumption has not only fueled domestic living standards, but also supplied a vast quantity of goods to the world.

Having been the first to industrialize, Western nations subsequently transferred many of their heavy and chemical industries abroad, primarily to China, driven by the dynamics of globalization, he said.

Currently, China’s total per capita electricity use has reached about 7,000 kilowatt-hours, which approaches the average level of member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

This aggregate figure masks a stark structural contrast: per capita residential electricity consumption in China stands at only about 1,000 kWh, roughly one-third of the level in post-industrial Western nations.

This disparity stems from the fact that in China, 65 percent of electricity is consumed by the industrial sector, Wang said, noting that the electricity consumption of the tertiary industry and residential sector accounts for about 16 percent and 19 percent of the total, respectively.

In developed countries, the electricity consumption of the secondary industry, tertiary industry and residential sector each accounts for roughly one-third of the total.

A substantial portion of China’s electricity ultimately serves global supply chains, Wang said.

He stressed the pivotal role of coal in meeting the huge electricity demand in China.

Coal dominates China’s fossil fuel reserves, constituting about 90 percent of the total, Wang noted. The country hinges on imports to meet about 45 percent of its natural gas and 70 percent of its oil demand.

“Therefore, for a long time in the past, coal has been the mainstay driving China’s power development and promoting its economic and social progress,” Wang said. “This is a reality that constitutes the fundamental rationale behind China’s reliance on coal.”

Driven by its higher combustion efficiency and the relative ease of monitoring and managing emissions, China has increasingly channeled coal into electricity generation, lifting the share used for electricity generation above 50 percent of its total coal consumption, he said.

Wang stressed that coal-fired power plants in China serve a critical dual purpose, providing not only electricity but also essential urban heating.

Two to three decades ago, heating was supplied by a large number of scattered small coal-fired boilers in the country’s urban areas. To address inefficiency and pollution, the country transformed coal-fired power plants into dual-purpose facilities that generate electricity and also supply heat.

Instead of wasting the heat produced during electricity generation, it is captured and channeled into heating networks. This dramatically boosts overall energy utilization efficiency, Wang explained.

“Currently in China, more than half of all coal-fired power plants operate as cogeneration units,” he said, adding that by replacing small, inefficient boilers with centralized plants, emissions are significantly reduced, air quality improves and energy use becomes far more efficient.

“Phasing out coal-fired power is contingent upon first resolving the heating supply challenge,” Wang said.

Since 2005, China has accelerated the development of renewable energy generation, with wind and solar power as the leading contributors. Today, one out of every three kWh of electricity produced in China comes from renewable sources, of which wind and solar power account for approximately 20 percent of the total electricity supply. This proportion already surpasses the global average, Wang noted.

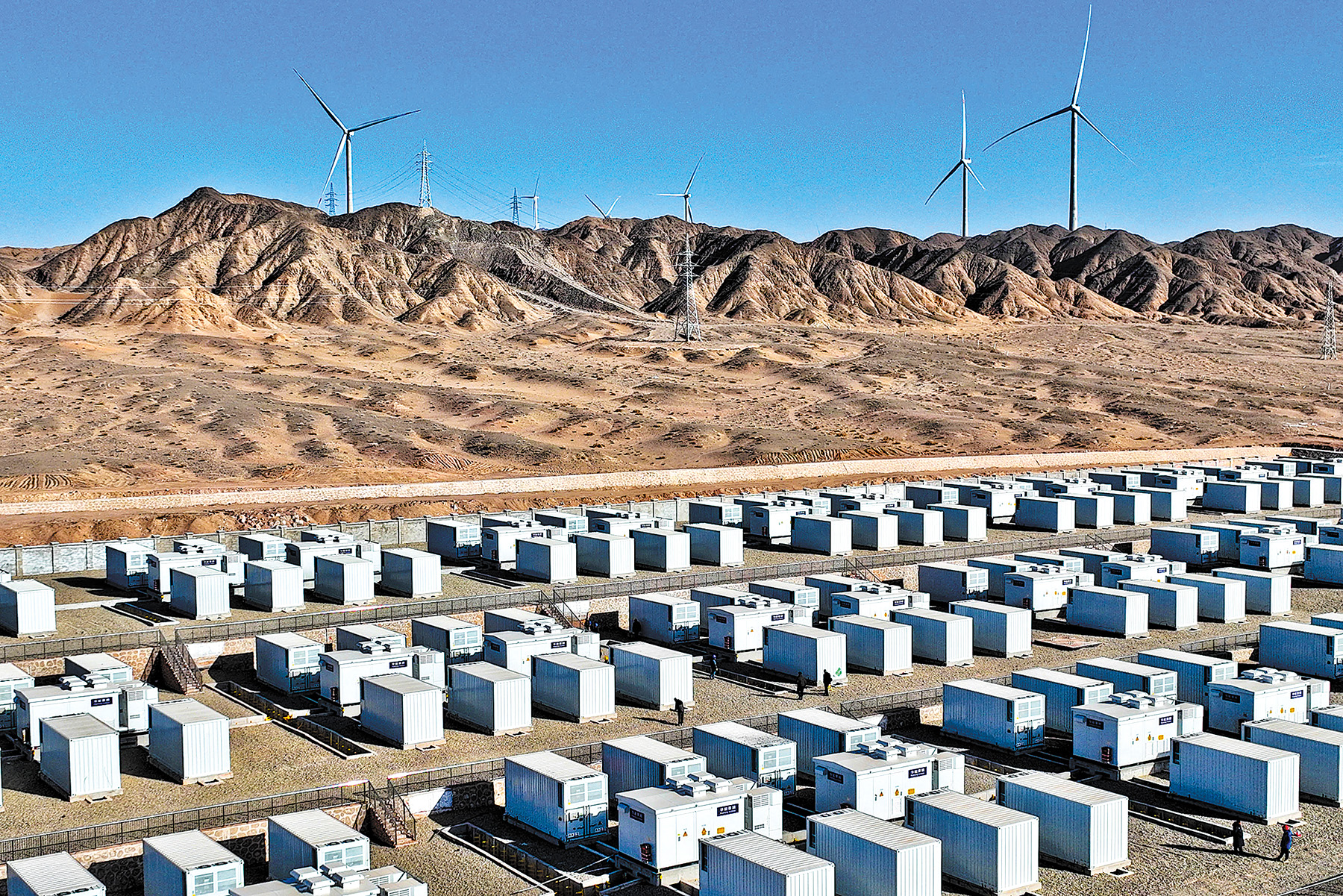

By the end of June 2025, the total installed capacity of renewable energy in China had reached 2,160 gigawatts, accounting for over 40 percent of the global total. Meanwhile, the combined installed capacity of wind and solar power had reached 1,670 GW, representing nearly half of the world’s total, according to a report from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

However, Wang pointed out that the sun does not shine at night, and the wind does not always blow, yet electricity demand is constant. “The grid must deliver power whenever users need it, day or night,” he said. “Renewables alone cannot guarantee that reliability.”

Globally, this intermittency is often managed by flexible natural gas-fired power plants, which have much smaller carbon emissions, he said.

But this solution is not scalable for China. Natural gas-fired power plants account for only about 5 percent of the country’s power generation capacity, limited by scarce domestic supply, high import costs, and competing priorities for residential and industrial use.

Wang noted that hydropower, largely designed for run-of-the-river generation in China, is poorly suited for on-demand regulation due to its dependence on seasonal and upstream water flows. Furthermore, nuclear power is predominantly a baseload power source and is not suitable for flexible load control.

“Historically, the task of providing flexible regulation for China’s power grid has fallen to coal-fired power plants,” he said.

What also underpins the indispensable role of coal-fired power in China is the high proportion of hydropower in the country’s energy mix, Wang said. A severe or prolonged drought could trigger a hydropower shortfall that other renewable energy sources might not be able to offset quickly enough, potentially leading to supply instability.

In 2024, hydropower accounted for 14.1 percent of China’s electricity generation, according to a report from the China Electricity Council.

The age of China’s infrastructure also dictates its policy. While the average Western coal plant is 50 years old and nearing natural retirement, China’s fleet is barely a decade old. These are modern, high-efficiency assets that represent billions of dollars in investment. Rather than discarding them, China is pursuing “clean transformations”, such as co-firing with hydrogen or ammonia, which could eventually bring coal emissions down to levels comparable to natural gas. This technological pathway allows China to keep its grid stable while progressively lowering its carbon footprint.

Wang emphasized that the core principle of China’s energy strategy is that, while some growth in coal power capacity may occur, efforts must focus on actively minimizing its actual use and prioritizing new energy sources for power generation whenever possible.

He likened coal-fired plants to a heavy-duty laborer who steps in only when other sources, such as solar and wind, are unable to work.

Coal-fired power plants in China are usually designed with an annual utilization of 5,500 hours. According to the China Electricity Council, however, their average annual utilization stood at only 4,628 hours in 2024.

Wang noted that as the cost of renewable energy generation in China continues to decline, steady progress has been made in enhancing the stability of renewable power systems, while electricity demand-side management is also improving its ability to adapt to evolving dynamics.

From an overall perspective, maintaining the stable operation of the entire power system, including the grid, other power sources and energy storage, still involves high costs, he said. This includes the expense of maintaining backup systems such as coal-fired power plants, which continue to provide essential support for China’s ongoing energy transition.

Li Qionghui, a retired researcher from the State Grid Energy Research Institute, noted that greater coal-fired power capacity does not automatically translate into higher emissions, and that annual utilization hours could drop to around 2,000 hours.

“The current expansion of coal-fired power capacity is driven by the grid’s need for flexibility,” Li said.

From a technological perspective, Li noted that while new power sources may emerge to replace coal-fired power in providing flexible load control, a new generation of coal-fired plants — through clean transformation measures such as hydrogen and ammonia co-firing — offers a potential pathway to achieve carbon emissions comparable to those of natural gas.

Currently, these next-generation coal-fired power plants remain in the demonstration phase, limited not only by high costs but also by operational challenges such as significant wear and tear, she said.

Li said that localization of wind and solar power consumption could be a potential way to relieve the country from its dependence on coal-fired power.

If more renewable energy could be consumed locally instead of being transferred to the grid for distribution, the grid would no longer have very high demand for flexibility, which would also reduce the demand for coal-fired power.

According to a guideline released last month by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, new industrial parks must consume at least 60 percent of their renewable energy on-site.

China does intend to reduce its reliance on coal-fired power, but this must be done while safeguarding its own energy security and maintaining stable development, Li said.

Ultimately, the nation’s strategy is rooted in long-term sustainability rather than an inherent attachment to fossil fuels. The expansion of coal capacity is a pragmatic response to the challenges of energy security, urban heating and the inherent volatility of green energy. By maintaining a robust backup system, China is creating the stable environment necessary for its renewable sector to continue its world-stunning growth.

The transition is driven by a dual necessity: cutting emissions while ensuring that the power never goes out, Li said.

Contact the writers at houliqiang@chinadaily.com.cn