Hong Kong’s cash-strapped arts heart is pursuing new revenue streams, including the disposal of residential properties and increased collaboration with Chinese mainland and overseas museums, to solidify the city’s status as Asia’s premier platform for arts and cultural exchanges between East and West. William Xu reports.

The West Kowloon Cultural District (WestK) — the symbol of Hong Kong’s cultural efflorescence — has found itself in a dilemma, grappling with an acute funding crisis despite tens of billions of dollars having been poured into its development and operations.

Managers of the arts centerpiece, which is home to the coveted Hong Kong Palace Museum (HKPM) and Xiqu Centre — the face of Chinese opera — say it’s in dire financial straits and unable to see the completion of all its planned facilities. One option is to raise cash by building and selling 1,995 residential flats on the site.

READ MORE: WKCDA welcomes govt approval of plan to ease funding woes

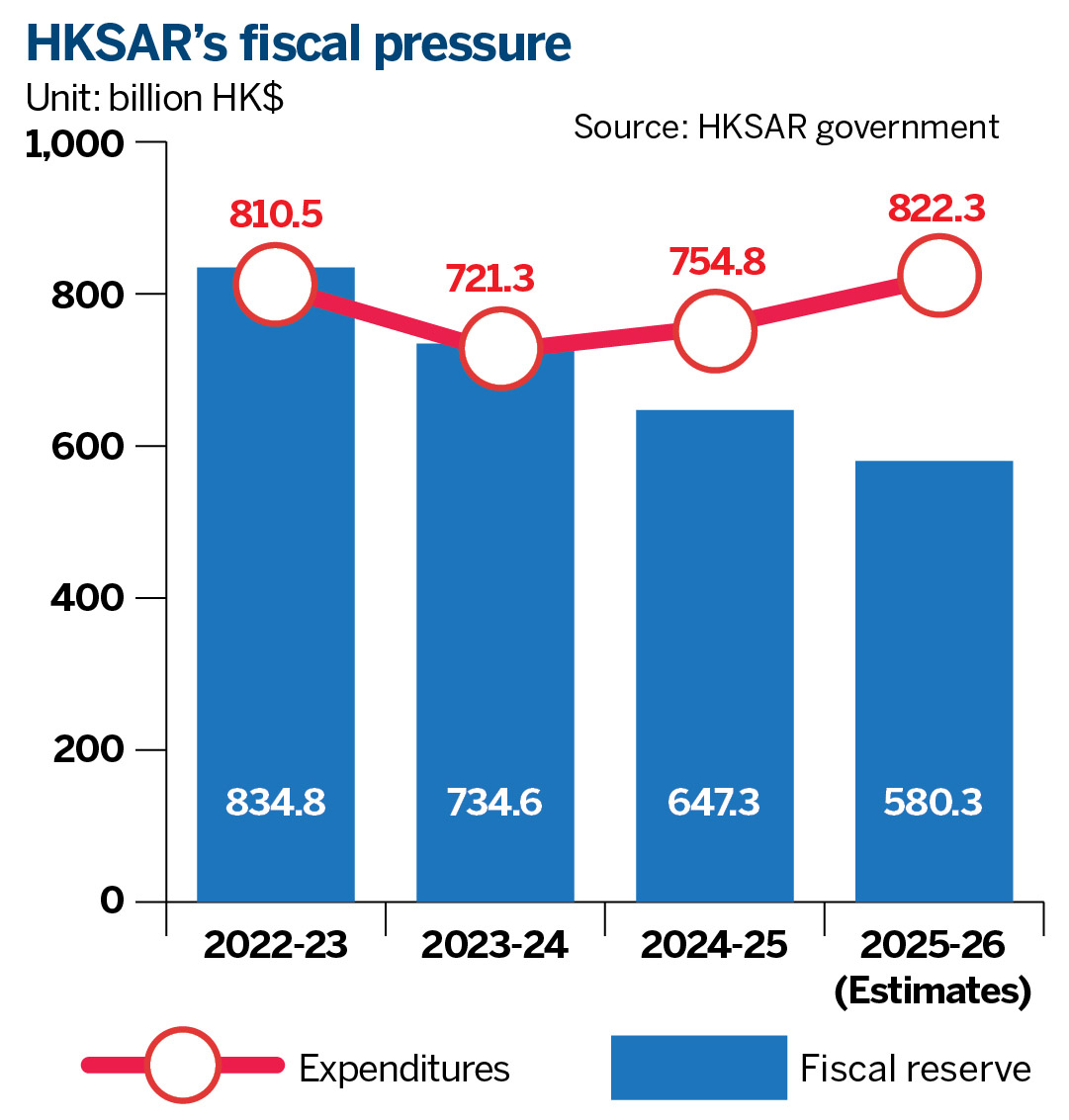

Policy incentives from the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government over the years, as well as external capital, have failed to get the arts district out of the doldrums. Its massive deficit continues to bleed. The financial strain stems not only from over-optimistic projections, but also points to a more fundamental challenge — the feasibility of achieving financial sustainability for public cultural facilities.

The 18th and 19th centuries had seen a proliferation of museums, theaters and libraries in urban life worldwide. They won broad recognition as essential public services in the 20th century and mushroomed following World War II. On the Chinese mainland, the number of public libraries and museums had soared from 55 and 21 in 1949, respectively, to 3,176 and 4,918 in 2018. Among some 16,000 museums built in the United States in the early 21st century, almost 90 percent of them were founded after the 1950s.

Hong Kong also witnessed a post-war boom in public cultural venues, notably the completion of Hong Kong City Hall, the Hong Kong Museum of Art and the Hong Kong Cultural Centre between the 1960s and 1980s.

Challenges encountered

Not all major cultural institutions are government-run, like the British Museum or China’s National Centre for the Performing Arts. Many of them, such as the US Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Getty Center, are managed by private or non-profitmaking groups that are responsible for most of the funding. For some, growing financial support from the authorities has been forthcoming over the past decades.

The WestK envisions a hybrid financing mode. A one-off HK$21.6 billion ($2.76 billion) endowment from the SAR government in 2008 was meant to cover initial construction and other expenses. It was estimated that the grant’s interest and investment income, combined with rental proceeds from retail, dining and entertainment facilities that make up 16 percent of the zone’s total floor area, would be sufficient for the project to break even.

However, a prolonged planning and public engagement process set the district’s development back for years. Construction of its first major facility — the 1,100-seat Xiqu Centre — couldn’t proceed until 2013. By then, building costs had doubled, compared with 2006 estimates, due to rising building demand and an evolving economic climate. The annual investment return rate between 2008 and 2014 averaged just 2.5 percent, far short of the projected 6.1 percent.

In 2016, while the core segments of the WestK’s first-phase development — Xiqu Centre, M+ museum and Freespace — were still being built, the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority (WKCDA), which manages the district, said that, besides the remaining HK$20 billion in reserves, it required a further HK$11.7 billion to proceed with the construction of the remaining facilities.

In December 2016, the SAR authorities gave the nod for the WKCDA to develop the 40-hectare district’s hotel, office and residential projects that took up about 43 percent of the total floor area, using a “build, operate and transfer” model, and share its income with private developers.

The Hong Kong Jockey Club fully funded the construction of the 13,000-square-meter HKPM, adding a new “must-visit” to the district without posing new financial burdens.

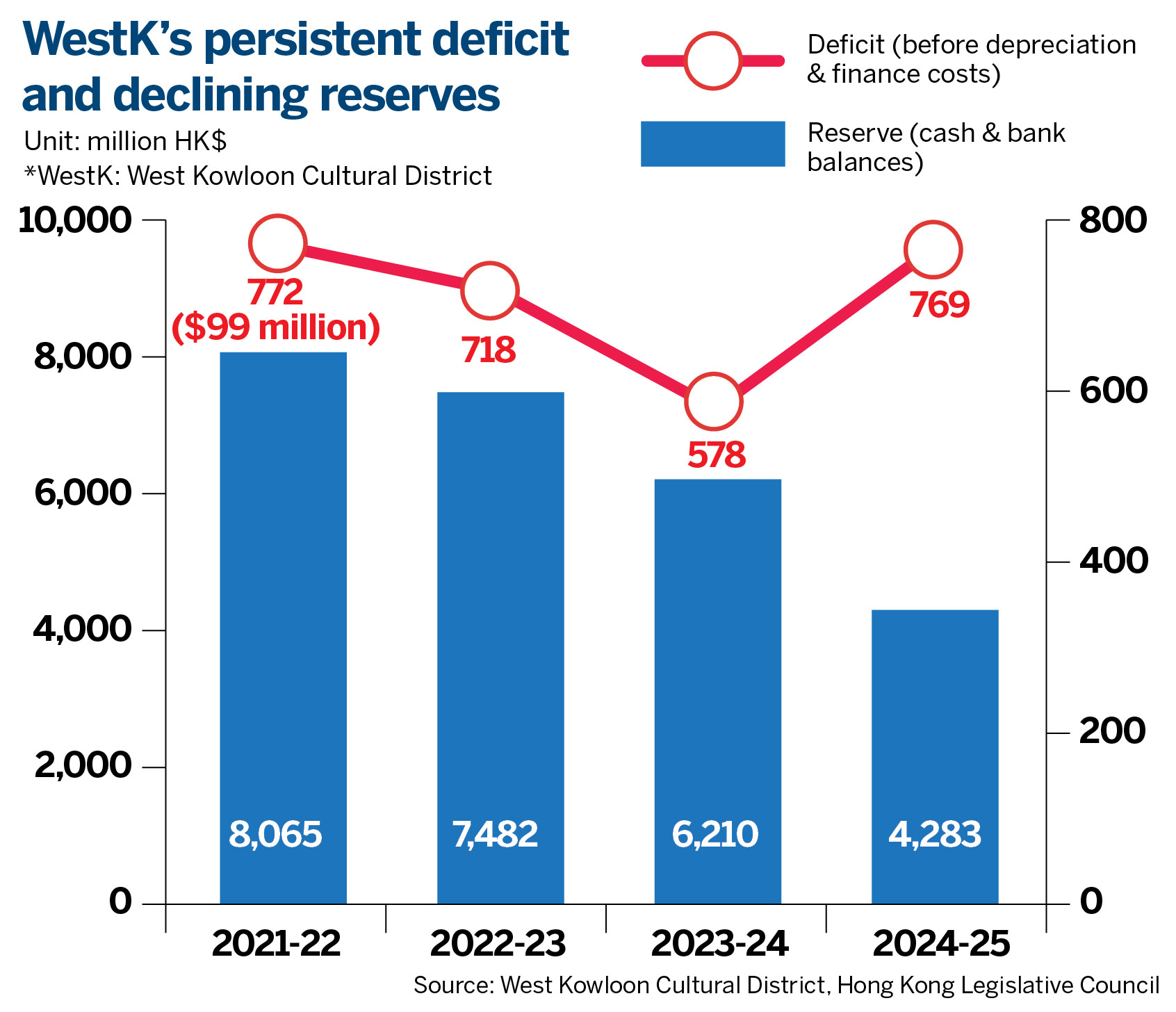

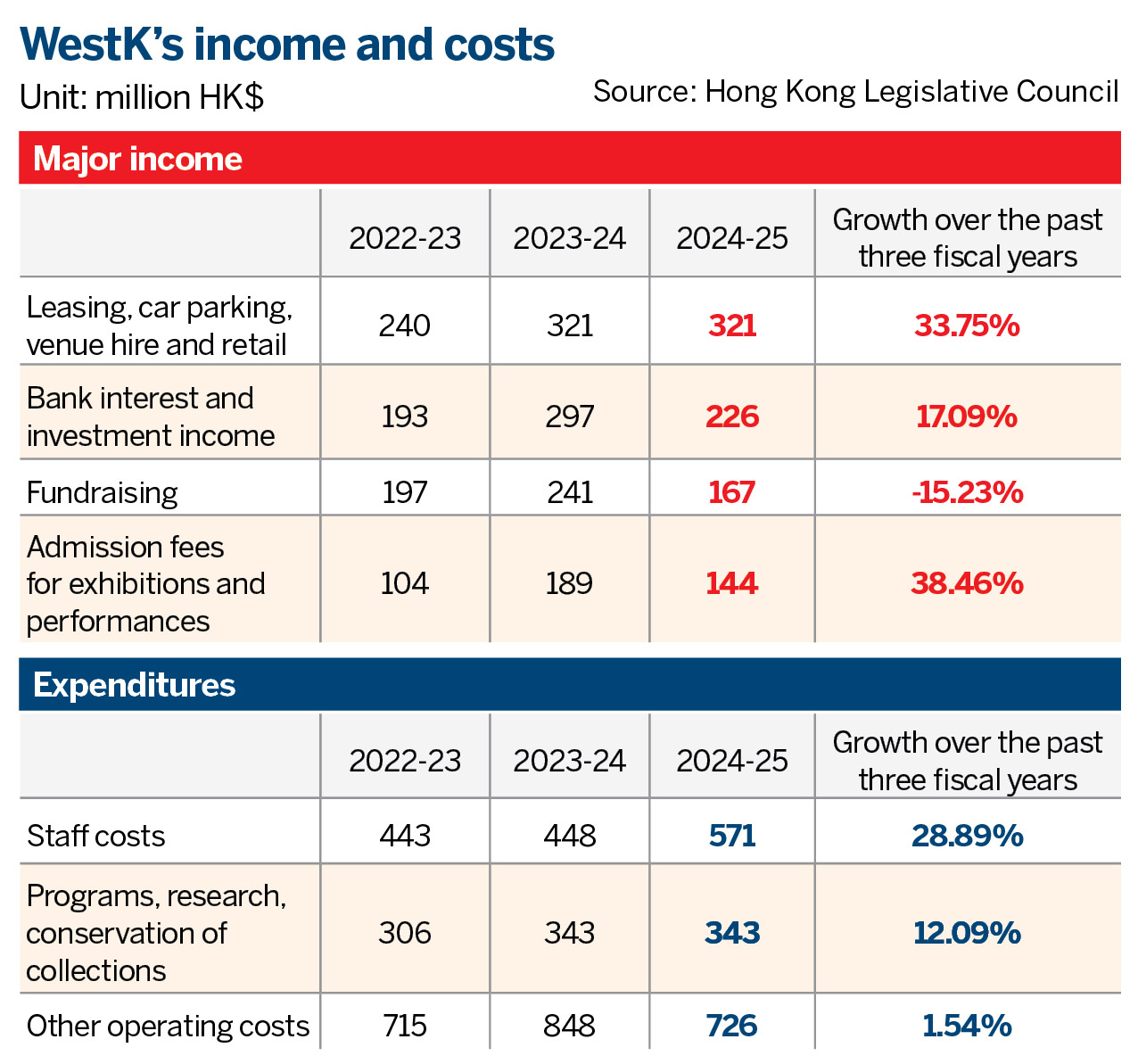

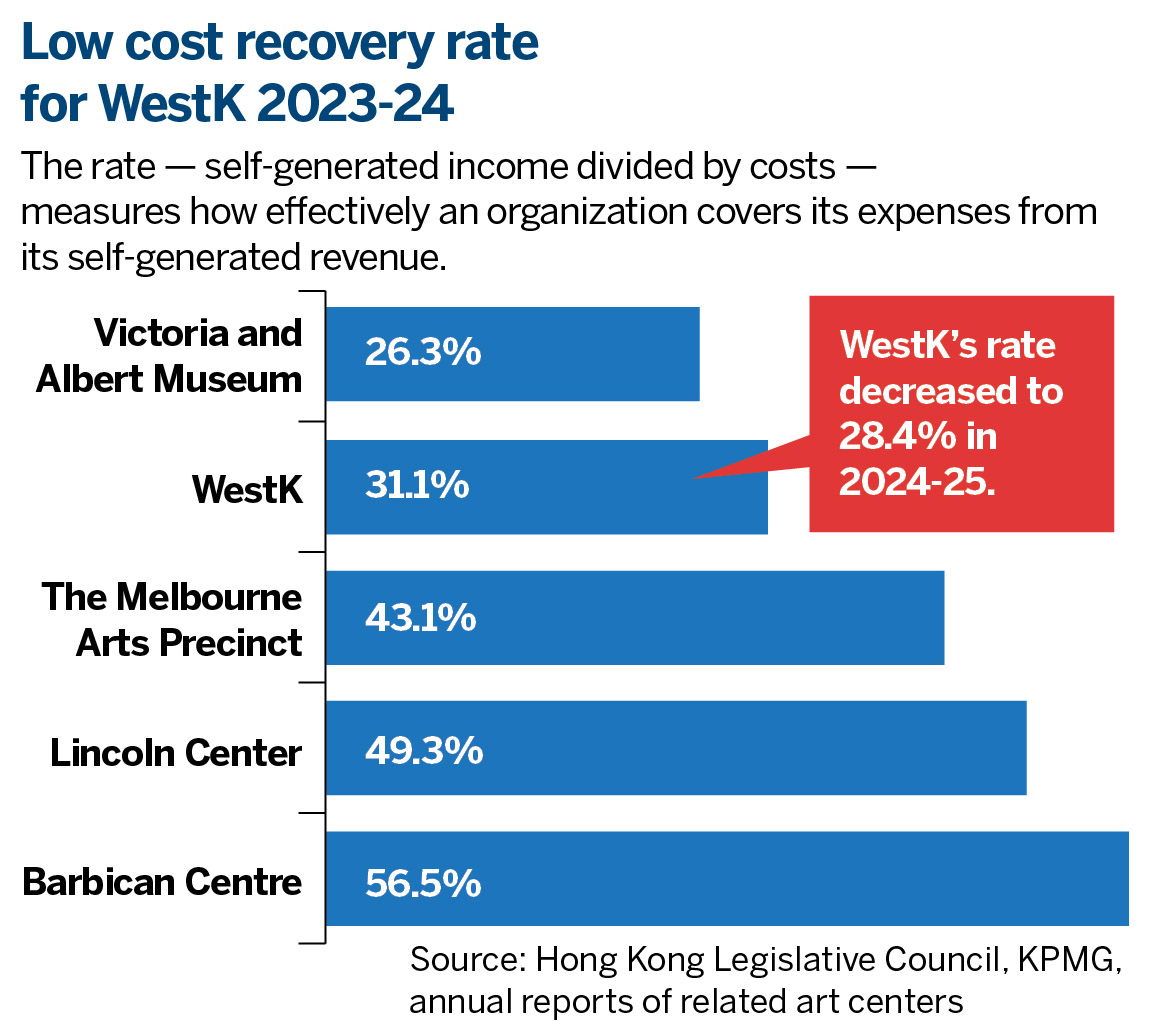

By the 2022-23 fiscal year, the major facilities from the first development phase, and the HKPM, had been completed, generating HK$746 million in revenue annually. But the arts hub’s expenditure surged to HK$1.46 billion, resulting in a deficit of HK$718 million. The annual income-expenditure gap narrowed to HK$578 million a year later, but rebounded to HK$769 million in the 2024-25 fiscal year.

The authorities launched another rescue bid last year by allowing the WKCDA to sell the residential portion under the 2016 arrangement, involving a floor area of 170,280 square meters, to generate cash flow that’s expected to keep the district running for a decade.

Details announced in May outlined plans for seven residential towers with 1,995 units to be completed by 2032.

Based on spending on building infrastructure borne by the government, such as the HK$23.5 billion integrated basement project, the direct public funding invested in the WestK had exceeded HK$45 billion. Yet, the district is still far from its self-financing commitment, leading to several major facilities, such as the Centre for Contemporary Performance, being suspended or put on the back burner.

Search for solutions

Bernard Charnwut Chan, who was announced as the new chairman of the WKCDA board in September, has pledged to boost income through the leasing of venues, sponsorships and product sales, saying the strategy of “using business to support cultural facilities” has been hindered as many commercial facilities have yet to be completed.

The district’s HK$21.6 billion government grant is depleting, threatening its key revenue stream. While contributions from ticket sales remain minor, commercial income from leasing and retail has gone up by nearly 34 percent in three years, becoming its second-largest revenue source.

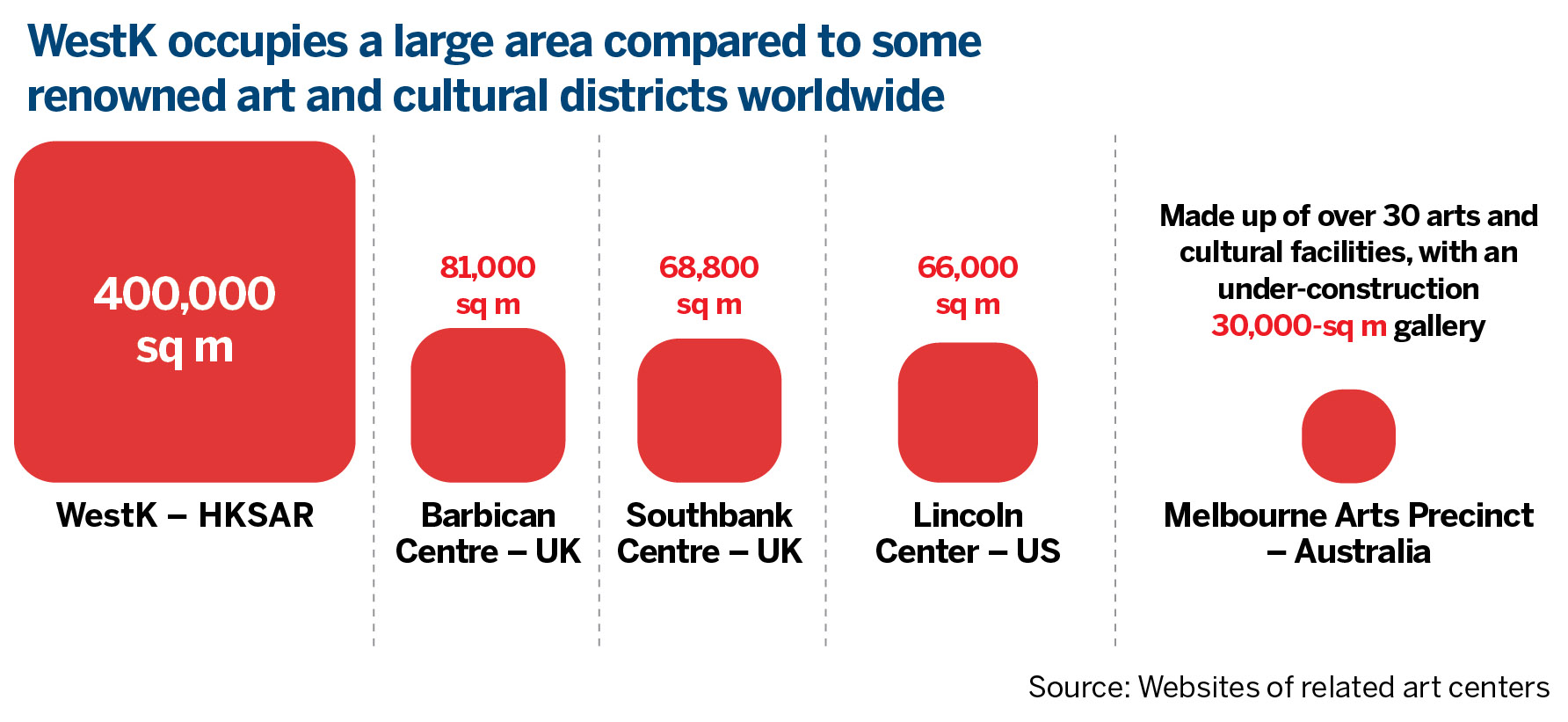

Fundraising typically accounts for 40 to 60 percent of revenue for major cultural districts — such as Australia’s Melbourne Arts Precinct and the Southbank Centre in London, the United Kingdom — but accounts for only 20 percent of revenue for the WestK, reflecting significant growth potential.

Finance scholar Simon Lee Siu-po says the WestK must further optimize its shopping, catering and exhibition strengths as they are lifelines for the district’s financial sustainability, apart from having to face fierce competition. The current economic climate also makes fundraising particularly challenging.

A report by the International Council of Museums in January this year pointed to a global decline in public funding for museums, and urged facilities to shift toward self-financing or hybrid models to survive.

The Derby Museums, which operates three cultural facilities in central England, had once heavily relied on public funds like many of its counterparts in the country, until a fiscal austerity drive across the country from 2010 changed the landscape. Funding from the local authorities was halved in five years, forcing the museum’s operator to diversify its business model. It succeeded. In the 2023-24 fiscal year, only 37.8 percent of the museum’s income came from public grants — a dramatic decline from 97 percent in 2014.

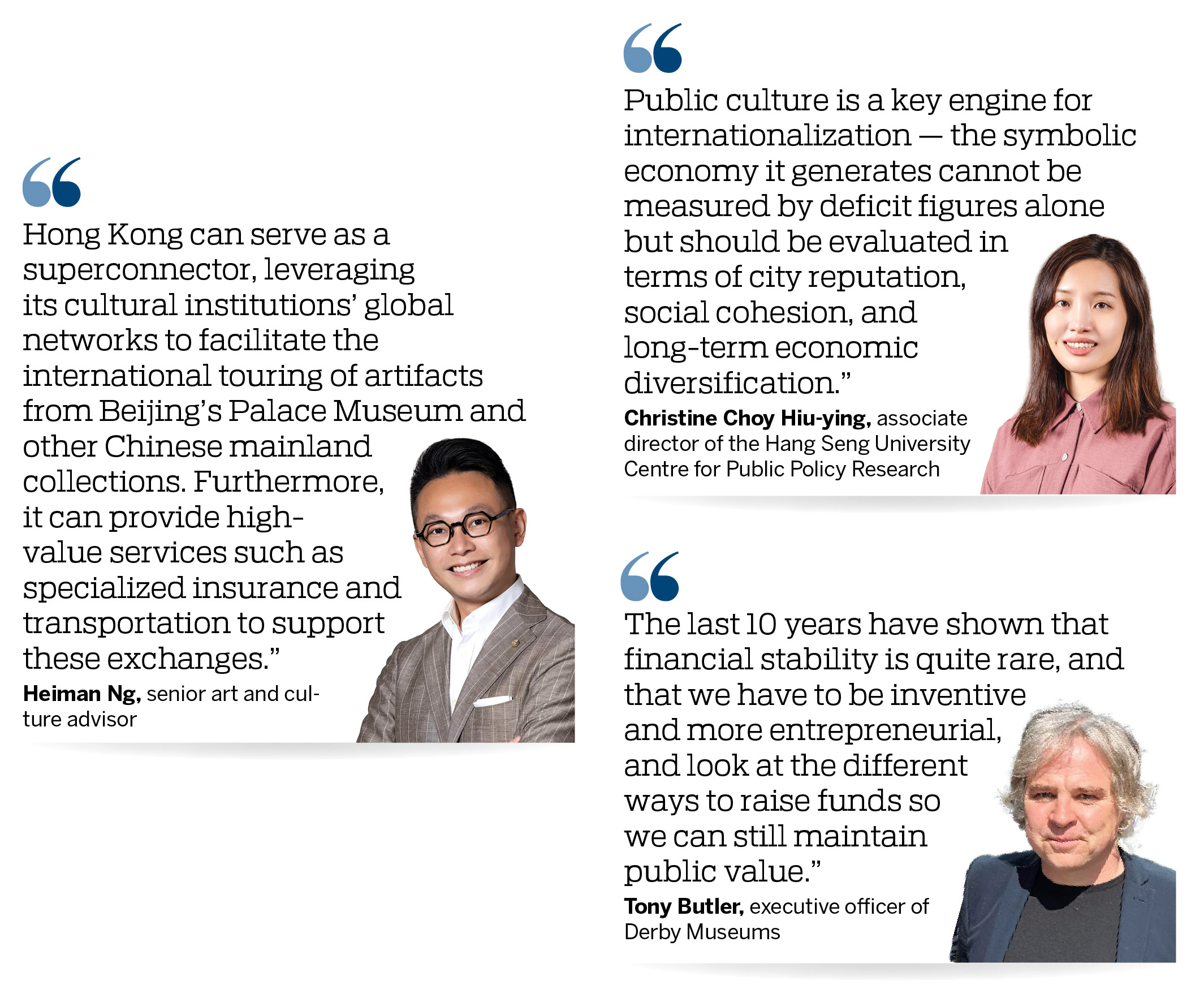

“We have to be more commercially minded and entrepreneurial,” says Tony Butler, executive officer of Derby Museums, citing achievements in raising more funds from trusts and foundations, while encouraging small-amount donations through nudges, building an endowment that can generate returns every year. On the other hand, museums have scaled back programming and exhibitions and hired fewer staff to “fit in with the current financial circumstances”, he says.

The Derby Museums rents out its venues for conferences and wedding receptions. A large on-site kitchen enables its staff to provide catering for events, further boosting earnings from the hiring of venues. “I think, for years, organizations just took it for granted they would exist because the state continued to fund them,” Butler says, noting that the struggles over the past decade have been a valuable lesson to teach museums to be inventive and more entrepreneurial to raise funds, while maintaining public values through exhibitions and learning programs.

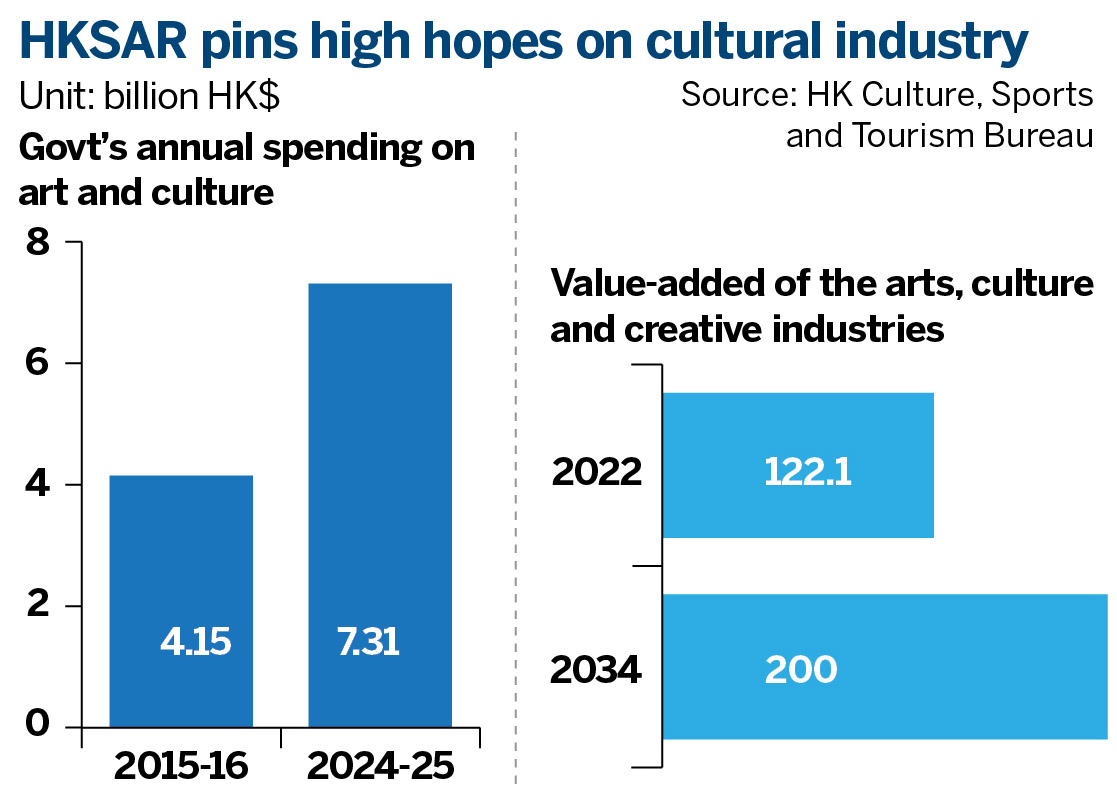

Apart from public values, Hong Kong’s policymakers expect the government’s investments to pay back in other areas.

“Cultural facilities have an obvious externality from the economy’s perspective,” says Francis Lui Ting-ming, professor emeritus at the Business School of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “After visiting the cultural facilities, tourists will also make purchases or have meals nearby, benefiting shops and cha chaan tengs (Hong Kong-style cafes) in the area,” he says.

A 2015 report by the Arts Council England — a public body dedicated to supporting arts and cultural venues — said every pound of funding it provides generates a payback of 5 pounds ($6.70) in tax contributions from the cultural and creative sector as a whole.

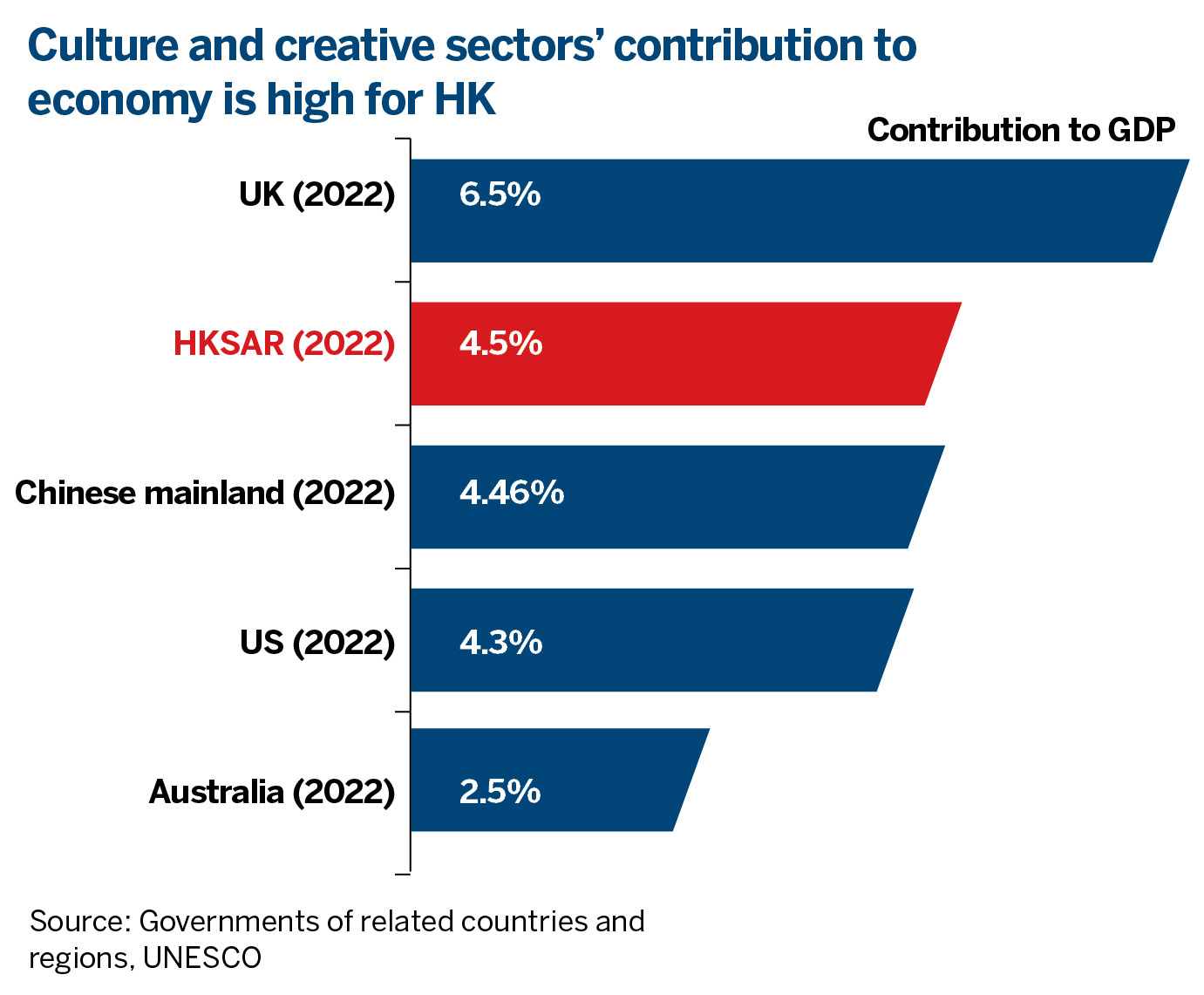

The cultural and creative industries are powerful economic drivers worldwide, contributing 4.59 percent to the Chinese mainland’s gross domestic product, and 4.2 percent to US’ GDP in 2023. In Hong Kong, the proportion of non-public cultural services in the GDP pie is about 4.6 percent.

Christine Choy Hiu-ying, associate director of the Hang Seng University Centre for Public Policy Research, says public culture delivers significant social, educational, and economic benefits that are often not fully captured by conventional accounting. “They promote civic engagement, social cohesion and intercultural literacy, all essential qualities for a thriving society like Hong Kong.”

Cultural districts also act as engines for tourism, education, the creative industries and international branding, generating value that accumulates over decades, she says.

The WestK drew more than 15 million visits in the 2024-25 year, including 1.1 million participants on learning programs. Its value-added contribution to Hong Kong’s GDP is HK$3.78 billion.

Lui believes the district’s economic outcome has far exceeded its HK$718 million deficit. Those externalities, like the heat and light emitted from a burning candle, may offer a more accurate measure of the WestK’s gains and losses than financial statements alone, according to experts.

Global Collaboration

So far, the WestK has signed 34 collaboration agreements with mainland and overseas partners — a strong network that Choy believes can improve its financial sustainability. “Hosting more global events and engaging with leading international artists expands audiences, drives ticket and sponsorship revenue, and also positions Hong Kong as a global cultural capital, reinforcing its creative economy and soft power.”

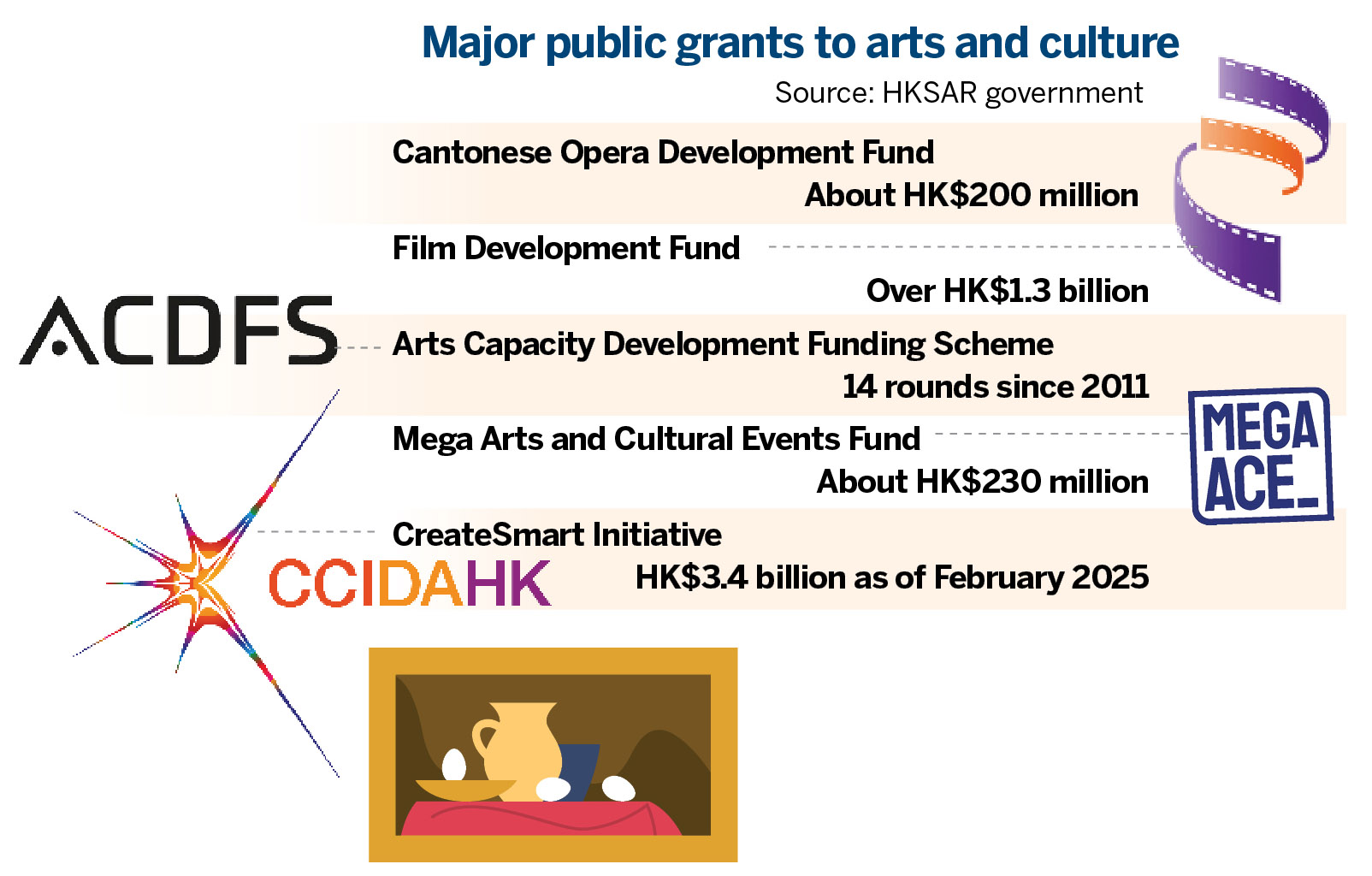

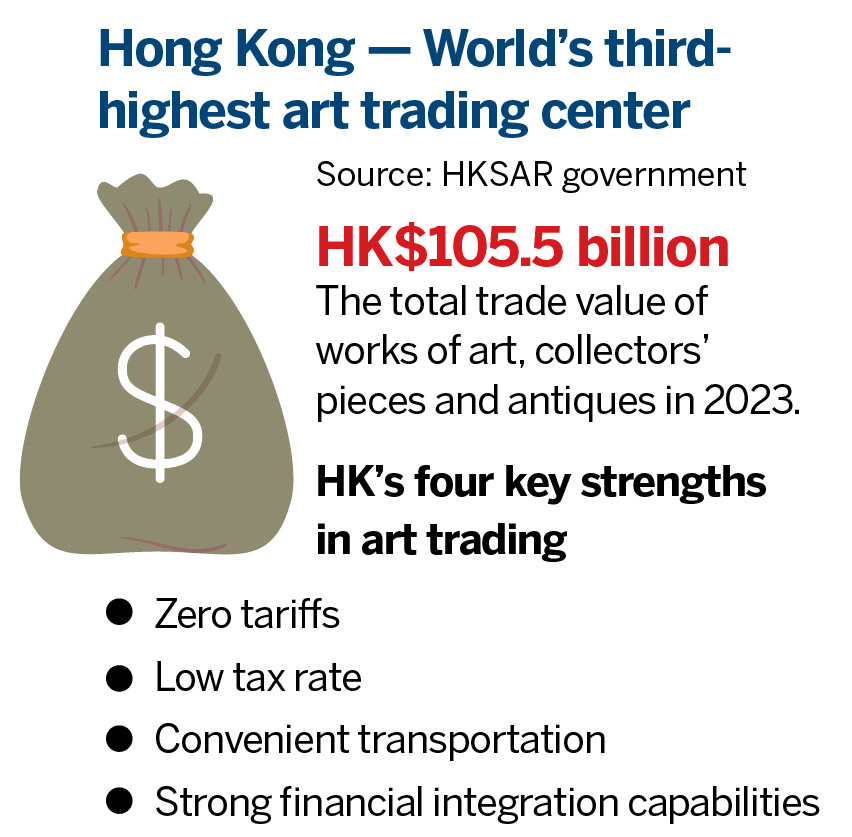

In a bid to bolster Hong Kong’s cultural sector — a key national mission outlined in the nation’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) — Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu has proposed several initiatives, including the establishment of a training institution called “WestK Academy” within the district, and promoting art trading in the city.

Heiman Ng, senior art and culture advisor, notes that the prestigious collections of the HKPM and M+ museum require professional stewardship, including conservation, restoration and thoughtful curation, to maximize their cultural and educational value. The proposed academy, he says, holds “significant potential” to cultivate local talent with these specialized capabilities.

Ng says Hong Kong should strengthen collaboration with museums on the mainland and those overseas, providing value-added services like specialized art transportation and insurance.

Choy believes a bustling art trading will create greater synergy among public museums and the commercial art market, enabling not only increased revenue streams through art fairs and auctions, but also cementing the city’s position as Asia’s premier platform for cultural and artistic exchange between East and West.

The WestK is proactively pursuing new revenue streams. The new West Kowloon Quay, due to open later this year, will launch a ferry route to Central that’s expected to significantly shorten travel time from Hong Kong Island, while offering new business opportunities.

A selection of government-run museums will start leasing out venues for commercial and private events on days they are closed to the public following Lee’s pledge to enhance public facility services. While the initiative may create short-term headwinds for the WestK, it can ultimately serve as a valuable case study in balancing market-driven revenue with broader social missions — a challenge the WestK must also navigate.

Next Actions

- Control expenses and increase incomes

- Adopt more entrepreneurial mindsets

- Balance market-oriented pursuits and public mission

- Enhance cross-border collaboration

- Develop surrounding industries to bolster cultural sector

Contact the writer at williamxu@chinadailyhk.com