After months of lively debate about its nature, an inscribed rock carving near a lake in Madoi county, Qinghai province, has been identified by the National Cultural Heritage Administration as being from the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

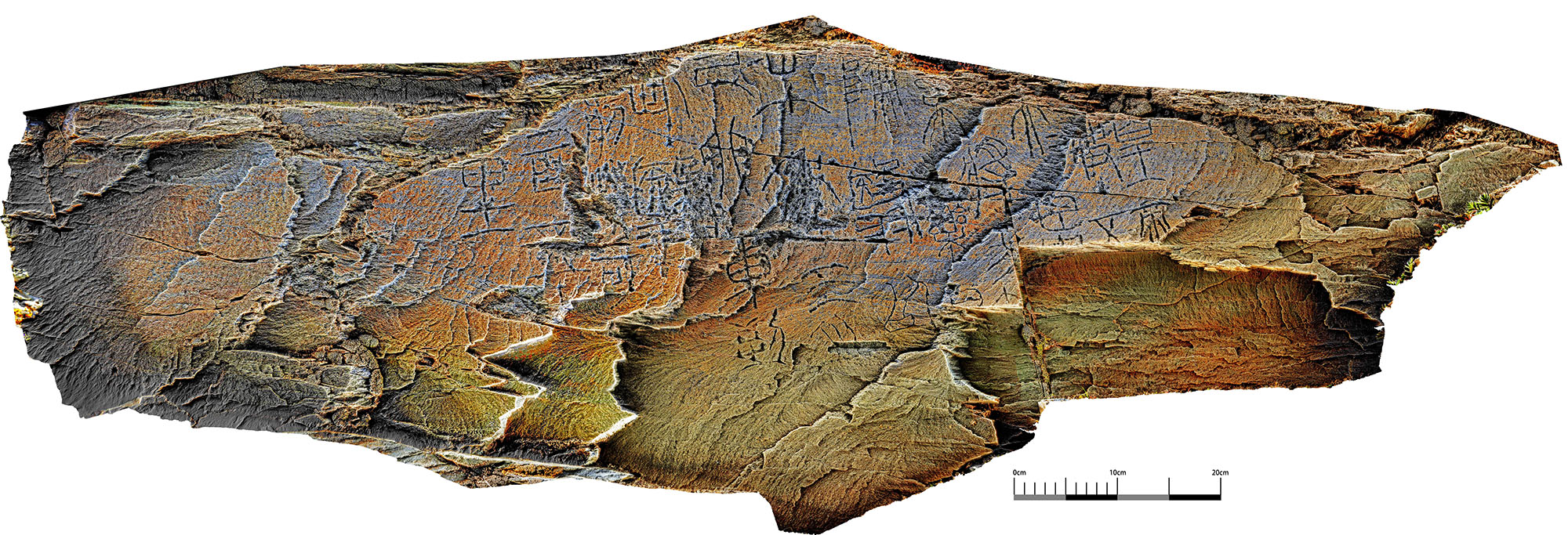

The 37-character inscription was found in 2020 on a rock along a lakeside slope, about 4,300 meters above sea level. It is of typical Qinera zhuanshu, or seal script writing style. The characters are spread across an area of 0.16 square meters, 19 centimeters above the ground.

Tong Tao, an archaeologist with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, arrived at the site in 2023 and realized its extraordinary significance.

Except for some unclear characters, he recognized that the surviving words indicated that the carving was a historical recording that was absent from previously known documentation.

The characters documented that Qinshihuang, the first emperor of China, had sent a high official named Yi on a mission to lead alchemists picking medicinal herbs on Kunlun Mountain.

It is the only known surviving Qin-era rock carving that remains at its original site and could provide a key reference on the location of Kunlun, a monumental sacred mountain in ancient Chinese culture that is hailed as the "ancestor of all mountains".

For example, in Erya, one of the oldest Chinese dictionaries, dating back to the third century BC, it is said that "the river comes from Kunlun", which corresponds to the location of the rock carving, which is close to the source of the Yellow River.

Nevertheless, after Tong, the archaeologist, wrote an article to release the earlier findings in Guangming Daily newspaper in June, the inscription ignited a lasting debate in the media. While some scholars supported its identification as being from the Qin Dynasty, others doubted its credibility and saw it as a modern fabrication due to its well-preserved condition.

Deng Chao, director of the National Cultural Heritage Administration's department of historic monuments, said at a news conference on Monday in Beijing that "laboratory analyses indicate that the inscribed rock consists of quartz sandstone, characterized by high abrasion resistance and strong weathering durability".

"Through high-definition examination, distinct tool markings on the inscribed characters were identified, indicating their creation using blunt-tipped engraving instruments, which matches with craftsmanship practices of the historical period," Deng added.

For the analysis, the administration organized expert panels involving archaeologists, historians, cultural relic conservators and calligraphy researchers, as well as experts in other fields, to conduct two rounds of field research and evaluation of the area surrounding the site.

Li Li, deputy director of the China Academy of Cultural Heritage, added that mineralogical composition studies and metallic element analysis conclusively ruled out the possibility of fabrication involving contemporary alloys or modern carving implements.

"The mineral types and contents inside the carved grooves and on the surface of the carved stone are basically consistent," she said. "This indicates that both the interior of the grooves and the rock surrounding the inscriptions have undergone long-term weathering."

Li Ling, a veteran archaeologist and paleographer at Peking University who conducted detailed, comparative studies of the rock carving in Madoi and other confirmed Qin inscriptions, said, "Most expert panel members agreed with the conclusion that these characters are of the Qin era, though this writing in the wilderness has some variation compared with those already documented."

Different chiseling methods were used on the carving, showing that its creator or creators did not deliberately pursue a uniform format and were more casual in dealing with different conditions of the rock base.

Dating evidence also emerged from the special style of the characters.

For example, the character lun from Kunlun has a rare pattern that was known to exist only during the Qin Dynasty. This pattern is identical to one that appeared in a Qin documentation written on bamboo slip, an ancient writing material, that was unearthed in Hunan province in 2002, Li Ling said.

Recent evaluations have also clarified some of Tong's initial interpretations. Tong once deciphered two unclear characters as "twenty-six", indicating that the medicine-picking was done in "the 26th year of Qinshihuang's reign (including his rule as a vassal state king before he united China to become emperor)", or 221 BC, the year Qinshihuang died.

However, the expert panel finally concluded that it was "thirty-seven", or 210 BC.

"More questions still remain to be answered," said Li Ling.

ALSO READ: Writing on the wall

Wang Jinxian, director of the Qinghai Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, said that comprehensive archaeological research has also been conducted across a vast tract of land surrounding the rock carving. Within a 150-kilometer radius, 75 unmovable cultural relics from throughout ancient history were discovered.

"Archaeological research showed that this lakeside region had been an area of frequent human activities dating back to the Paleolithic period," he said, responding to some public doubt about why Qinshihuang's mission left carvings on this "desolate land".

Realizing its key value in historical, artistic and scientific studies, the local government immediately launched a comprehensive protection program for the rock carving. Protection and monitoring facilities were set up, and nearby traffic routes were adjusted accordingly.

Deng vowed that the site will also be given special attention during the ongoing process of applying for the site's inclusion on China's ninth list of national key protected cultural heritage sites.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn