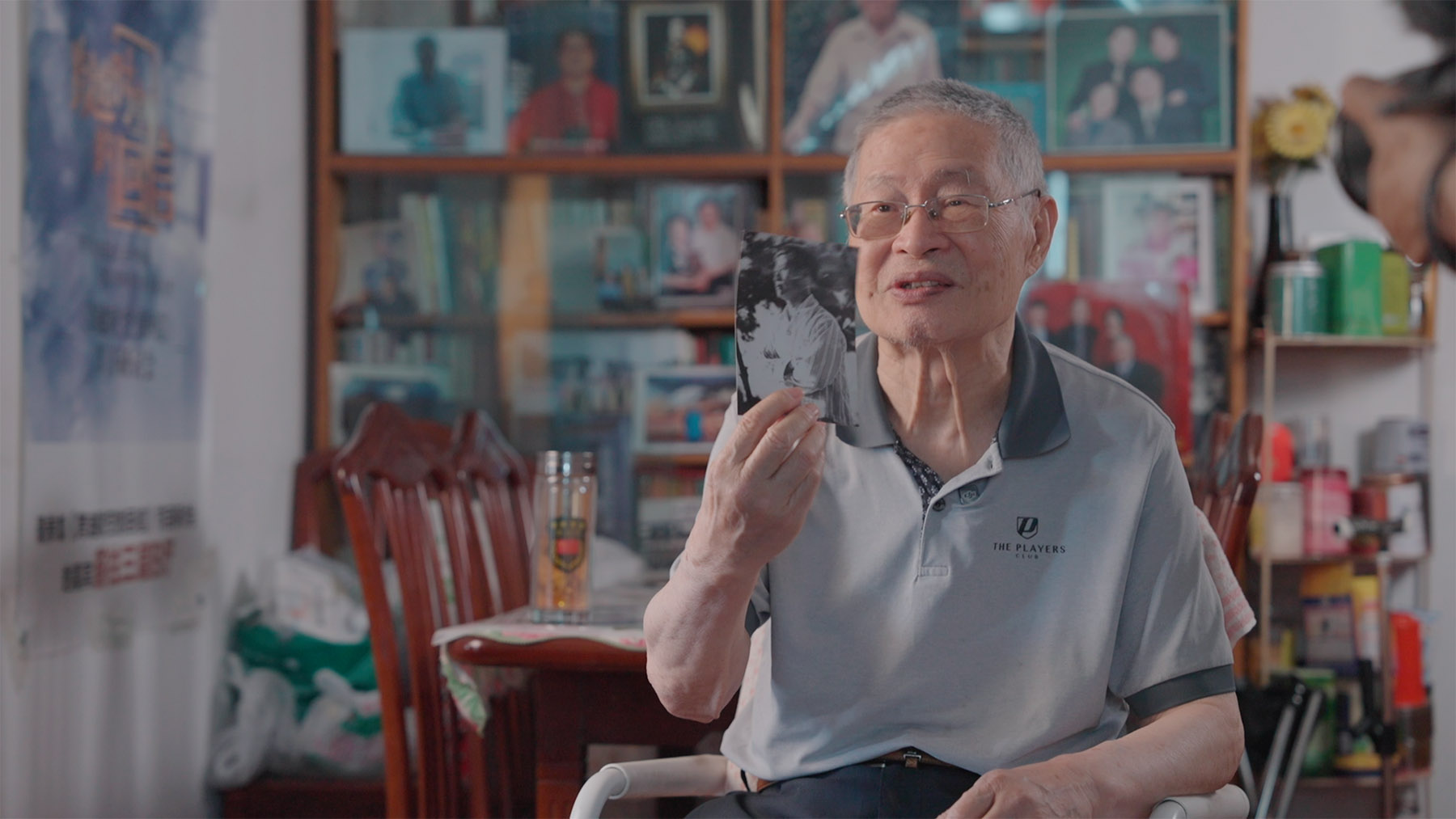

In his Beijing home, 83-year-old Lin Yimin cherishes a collection of letters left by his father, Lin Chengheng. These letters chronicle the growth of a patriotic young man from Taiwan into a proud member of the Communist Party of China during the struggle against Japanese aggression.

In October 1945, after hearing of the surrender of the Japanese, Lin Cheng-heng, who had fought against the Japanese in Myanmar and was recuperating in China's Yunnan province, wrote to his mother in Taiwan:

"The recovery of Taiwan fulfills my father's lifelong wish. If he knew, he would surely laugh in the afterlife. My disability (he had sustained severe injuries to his arms in the conflict) is nothing. If the nation can achieve victory and strength, if my compatriots in Taiwan can gain light and freedom, my sacrifice is worth it. Mother, please do not mourn my disability..."

READ MORE: Taiwan compatriots fought to liberate nation

These words, penned with difficulty, reveal a man who placed his country above himself. His son, Lin Yimin, who lost his father at the age of 7, keeps the letter as a cherished memory of his dad.

Born in 1915 into the illustrious Lin family of Wufeng, in Taiwan's Taichung, Lin Cheng-heng was part of a lineage marked by patriotism and resistance. The family, originally from Pinghe county in Zhangzhou, Fujian province, had prospered through camphor trade across the Taiwan Strait since the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

His grandfather, Lin Chao-tung, defended Taiwan against the French, while his father, Lin Tzu-mi, supported Sun Yat-sen's revolution, dedicating resources to the cause against the Japanese invaders in Taiwan.

In 1937, as Japan's aggression spread across China, Lin Chengheng abandoned his art studies and comfortable life to enroll in the Central Military Academy in Nanjing, Jiangsu province. Graduating in 1939, he participated in the Battle of Kunlun Pass in today's Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. He fought through encirclement by Japanese forces for four days, ultimately delivering crucial intelligence.

By 1944, the nationwide fervor against Japan reignited Lin Chengheng's passion. He aspired to join the Chinese Expeditionary Force in Myanmar. "My mother was pregnant with their second child and didn't want him to leave. But he said, 'Without a country, where is our home? '" Lin Yimin recalled.

In Myanmar, during his last battle, despite suffering severe injuries — 16 wounds over the body and bones fractured — he continued to fight until he collapsed from his wounds. A soldier found him barely alive and carried him to safety. After two major surgeries and four months of recovery, he survived but could never again clench his fists.

While recuperating, Lin Chengheng wrote to his mother: "Mom, do not grieve my disability; rejoice in our family's honor. You did not raise me in vain; I am now the bravest and most honorable of the Lin family."

The victory over Japan and his experience with the CPC and the Chinese Kuomintang prompted a profound shift in Lin Cheng-heng's beliefs. Recognizing the CPC as the future of China, he secretly joined it in 1946, working underground in Taiwan.

However, on Aug 18, 1949, just before the founding of the People's Republic of China, he was arrested by KMT agents. On Jan 30, 1950, at the age of 35, he was executed at Machangding in Taipei, shouting "Long live the motherland! Long live the people!"

Lin Yimin recounted: "His prison van passed by our home, and my father called out to my mother, 'Baozhu, come out quickly, I am going to the execution ground...' By the time she arrived, he was already gone..."

Before his execution, Lin Chengheng wrote farewell letters to his mother and son. In his letter to Lin Yimin, he urged him to be dutiful, polite, to honor his grandmother, and to aspire to be a person useful to society. To his mother, he wrote: "Thinking of my father, I must bear double the responsibility, so I tread his path of suffering and sacrifice, which are noble and glorious. Mother, do not mourn or worry for me. In life, we strive and sacrifice for duty; in death, we fulfill it."

ALSO READ: Veterans relive struggle against invaders

Lin Yimin said that during his childhood, his father was very strict with him and would discipline him with a feather duster if he made mistakes. But later, when he saw the paper flowers he crafted in prison and read the letters, he truly understood his father's love and expectations.

As a descendant of a martyr, Lin Yimin received support from the CPC to study and grow up in Beijing, where he eventually became a journalist. His home is adorned with photographs of his father, frozen in time as a young man in his 30s. This young handsome image, along with touching the scars of war he felt while swimming with his dad, have been Lin Yimin's treasured and lasting memories of his father.

Contact the writers at zhangyi1@chinadaily.com.cn