Lotte Lustig Marcus, a Jewish refugee in Shanghai in 1939, was a woman whose strength of character, intelligence, resourcefulness and courage will be remembered, Ho Manli reports.

Lotte Lustig Marcus (center) on a panel of survivors speaking at a 2019 program honoring Ho Feng Shan, jointly sponsored by the Chinese and Israeli consulates in San Francisco. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Lotte Lustig Marcus (center) on a panel of survivors speaking at a 2019 program honoring Ho Feng Shan, jointly sponsored by the Chinese and Israeli consulates in San Francisco. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Lotte Lustig Marcus, one of the last of the "Shanghailanders" — the 18,000 European Jewish refugees who fled to Shanghai to escape Nazi persecution during World War II — died at her home in Carmel, California, on Nov 19 at age 95.

A clinical psychologist well known for treating trauma sufferers, she was also active in humanitarian and educational work with migrant workers and multiple sclerosis patients.

In March 1938, two months before her 11th birthday, Lotte Marcus saw Adolf Hitler march triumphantly into her native Vienna after the Anschluss, the union of Austria and Nazi Germany, shattered the third-largest Jewish community in Europe and precipitated a refugee crisis.

The lives of 185,000 Austrian Jews changed overnight under the ensuing Nazi reign of terror. Lotte's father Oskar was fired from his job at the Austrian State Bank. Because she was Jewish, Lotte could no longer attend school or participate in the ice-skating shows she loved.

Nazi authorities told Jews they could leave if they could produce "proof of emigration" to some place that would accept them. However, as evidenced by the Evian Conference in July 1938, most Western nations refused to open their doors to Jewish refugees.

"It is difficult today to re-create the terrible climate of rejection and humiliation that existed for us," Lotte later wrote.

Lotte Marcus and her husband, Alan Marcus. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Lotte Marcus and her husband, Alan Marcus. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Lotte's father copied the addresses of all those with their surname of Lustig from American telephone directories, and Lotte wrote to them asking for help in her schoolgirl English. "We got almost 48 replies — all equally polite, equally firm that they couldn't help," Lotte recalled.

Then on Oct 18, 1938, Lotte wrote: "My father found himself standing in a long line in front of a building because someone had told him that the Chinese consul was giving out visas to Shanghai. My father happened to have our passports on him. He stood in line and retrieved (the) visas — 'just in case', he told us."

My late father, Ho Feng Shan, the Chinese consul general in Vienna, had devised an ingenious strategy to save Jews by issuing visas to the only accessible entry point in war-torn China — the port city of Shanghai. Shanghai required no entry documents, but the visas facilitated safe passage out of Nazi-occupied territories and put Shanghai on the map as a refuge of last resort for Jews.

To a Western European of that time, Shanghai was simply unheard of, and Lotte's mother Grete was horrified, she recalled. "Our expectations had been to migrate to a Western country — America, England, Australia, France, etc." Or even to neighboring Switzerland, Lotte said, until her mother learned that close friends had been murdered by the person they had trusted to guide them across the border.

Then, on Nov 9 and 10, the Nazis orchestrated an overnight anti-Jewish rampage in Austria and Germany, during which Jewish stores were looted, Jewish synagogues burned, and 30,000 Jewish males, including Lotte's uncle Alfred, were arrested and deported to concentration camps.

"In December, Alfred's body was sent to us. He died, we were told, of pneumonia, which he allegedly caught working in the freezing cold on road construction wearing the famed striped pajamas," Lotte recalled. "It was then that Shanghai no longer loomed as a distant possibility but became an immediate necessity."

The couple at their home in Carmel, California. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

The couple at their home in Carmel, California. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

In January 1939, Lotte and her parents set sail for Shanghai on the Conte Biancamano, one of the luxury liners of the Italian Lloyd Triestino Company which engaged in war profiteering by ferrying Jewish refugees to Shanghai and charging them for first-class tickets.

Arriving in a Shanghai ravaged by war and under brutal Japanese occupation could not have been a starker contrast to Vienna, or more shocking to European middle-class sensibilities, Lotte recalled, especially for her mother, who never recovered.

For the next eight years, Lotte's family survived with her father trading his stamp collection and Lotte taking odd jobs, including at a Chinese department store that sold tea biscuits to local foreigners. At the end of the day, Lotte recalled, she would scrape the bits of sugar at the bottom of the biscuit tin to bring home to her mother.

She utilized her English-language skills and ran errands for Chinese merchants. Every three months, she sold her thick brown hair by the ounce. She even started a little business with one of her boyfriends, turning Chinese comic books into bundles of toilet paper.

She was the first love of the most well-known Shanghailander, W. Michael Blumenthal, who later became the US secretary of the treasury in the Carter administration. She called him "Werner" and they remained friends for life.

In 1943, the Japanese ordered all the "stateless" Jewish refugees to move into a special designated area in Hongkou, which already had 100,000 Chinese residents. Living conditions became even harsher, with 10 people squeezed into one room, Lotte said. Dire poverty, hunger, disease and death were commonplace, and every summer, Lotte recalled, so was amoebic dysentery.

Lotte Marcus and Ho Manli's first meeting in 2003. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Lotte Marcus and Ho Manli's first meeting in 2003. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

Not long afterward, Lotte's father died of kidney cancer, leaving a teenage Lotte to support herself and her mother until 1947, when they were able to emigrate to the United States. After arriving in Los Angeles, Lotte found a job as a legal secretary at the Hollywood movie studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where she met the writer Alan Marcus. They were married in 1952 and settled in Carmel, California.

That is where I met Lotte in 2003. I had been researching and documenting the history of my father's rescue activities in Vienna and learned that she still possessed the passports and visas that my father's consulate had issued.

By then, Lotte had raised three children, finished college, obtained her master's degree and, in 1985, at the age of 57, earned a PhD in psychology. She had a successful clinical practice and had turned the post-traumatic stress she suffered from her wartime experience into a means to help others.

Our meeting was a revelation to both of us. For Lotte, learning that the visas her father obtained had a face behind them, that it had not been just a random bit of bureaucracy, but an act of kindness, led her to see the past with fresh eyes. For me, Lotte's ability to transcend her childhood traumas and memories, to see past experiences with adult eyes and to place them in a larger context, gave me a fuller understanding of that complex history.

For the next 19 years, Lotte spoke and wrote with unflinching eloquence about the harsh realities faced by the Jewish refugees in Shanghai. She gave credit where credit was due: to the wealthy local Jews and Jewish relief organizations who provided housing, soup kitchens and schooling for the refugee children, and facilitated the creation of an exile community.

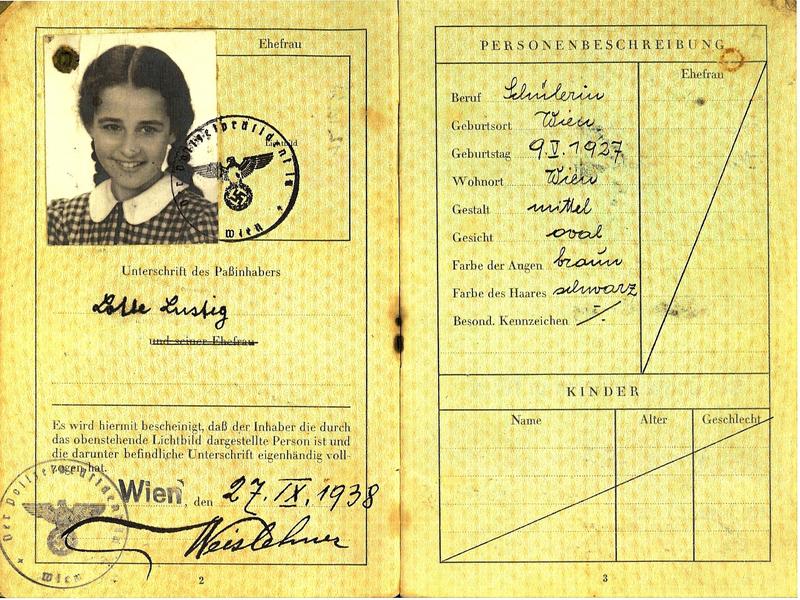

11-year-old Lotte Marcus' passport photo. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

11-year-old Lotte Marcus' passport photo. (PHOTO COURTESY OF HO MANLI)

She spoke with regret that neither she, nor her fellow refugees, ever learned the culture or language of their host country. The common struggle for survival had precluded any real social interactions with their Chinese neighbors, to whom the refugees were just another added "sliver of nakojin" ("foreigner" in Shanghai dialect), albeit poorer, Lotte recalled.

She decried a recent revisionist trend that embellished and distorted this Shanghai history into a "fictive tale" of hearts-and-flowers. "Nothing could be further from the essence of the actual experience," she wrote.

In her last years, Lotte often said how "lucky" she had been in life. But it was more than luck. It was Lotte herself: her strength of character, her intelligence, her resourcefulness, and her courage. My father would have been proud to have saved someone like her.

Ho Manli, the daughter of the late Chinese diplomat rescuer Ho Feng Shan, has been researching and documenting her father's heroism for the past two decades. She was one of the foreign editors who helped launch China Daily in 1981 and has continued to work with the paper on major projects such as the 1990 Asian Games, the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the launching of the paper's US edition.

Contact the writer at homanli@chinadaily.com.cn