Documentary sheds light on bravery of Chinese fishermen who saved drowning British prisoners of war during WWII

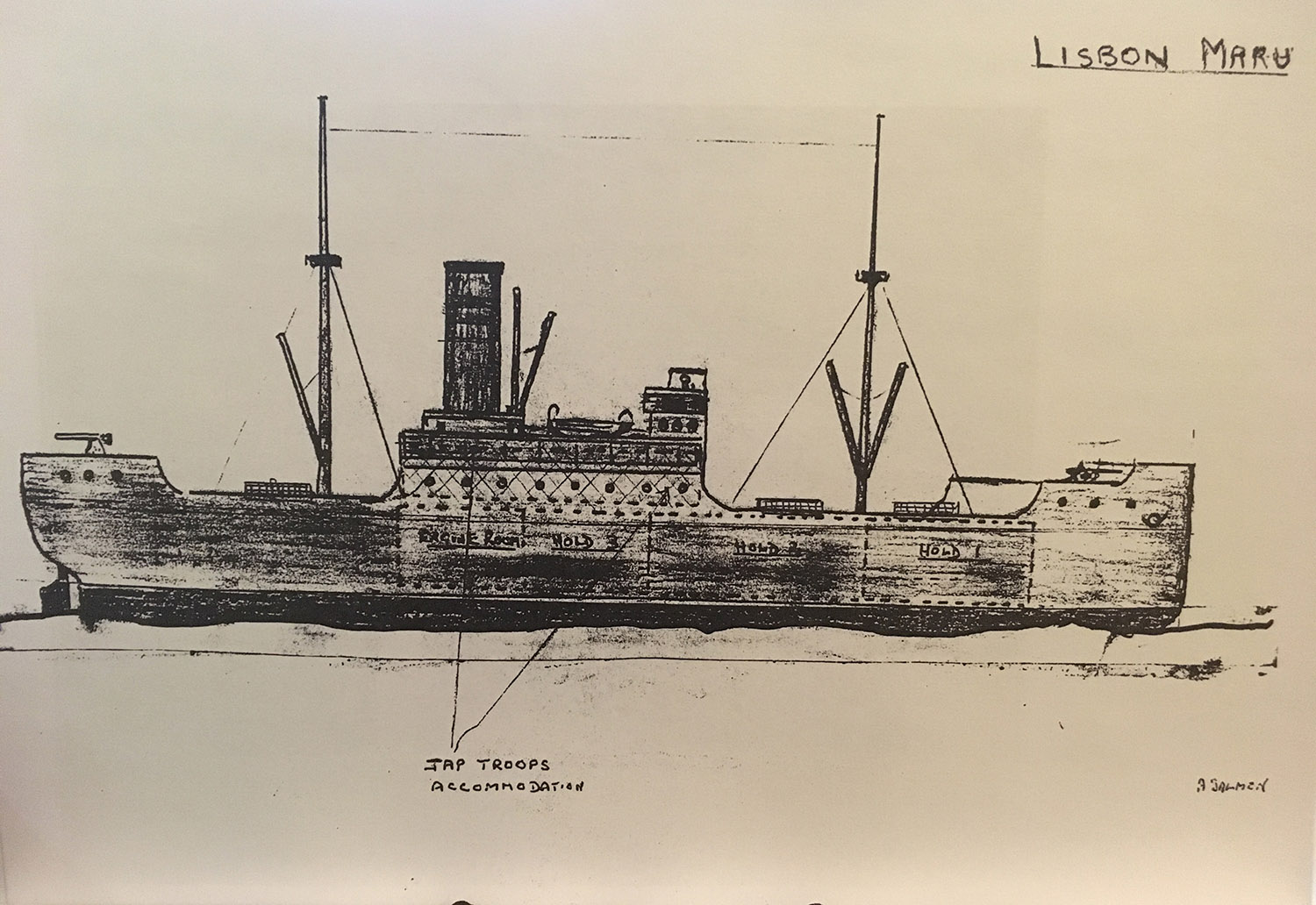

The cargo vessel Lisbon Maru was converted into a troop carrier by the Japanese army during World War II. In October 1942, while carrying about 1,800 British prisoners of war (POWs) from Hong Kong to Japan, it was torpedoed by a United States submarine off the coast of East China’s Zhejiang province.

The POWs were locked in the holds and left to drown. Some of them managed to escape, but were fired upon by Japanese soldiers. Chinese fishermen heard the incident from the shore and rushed to save 384 British soldiers. The ship sank with the loss of 828 POWs who were either shot or drowned.

In 2015, when President Xi Jinping was making a state visit to the United Kingdom, he made a speech at a state banquet in which he referred to the Chinese fishermen’s rescue of the British POWs as an example of friendly ties that will never fade and an invaluable asset in relations between China and the UK.

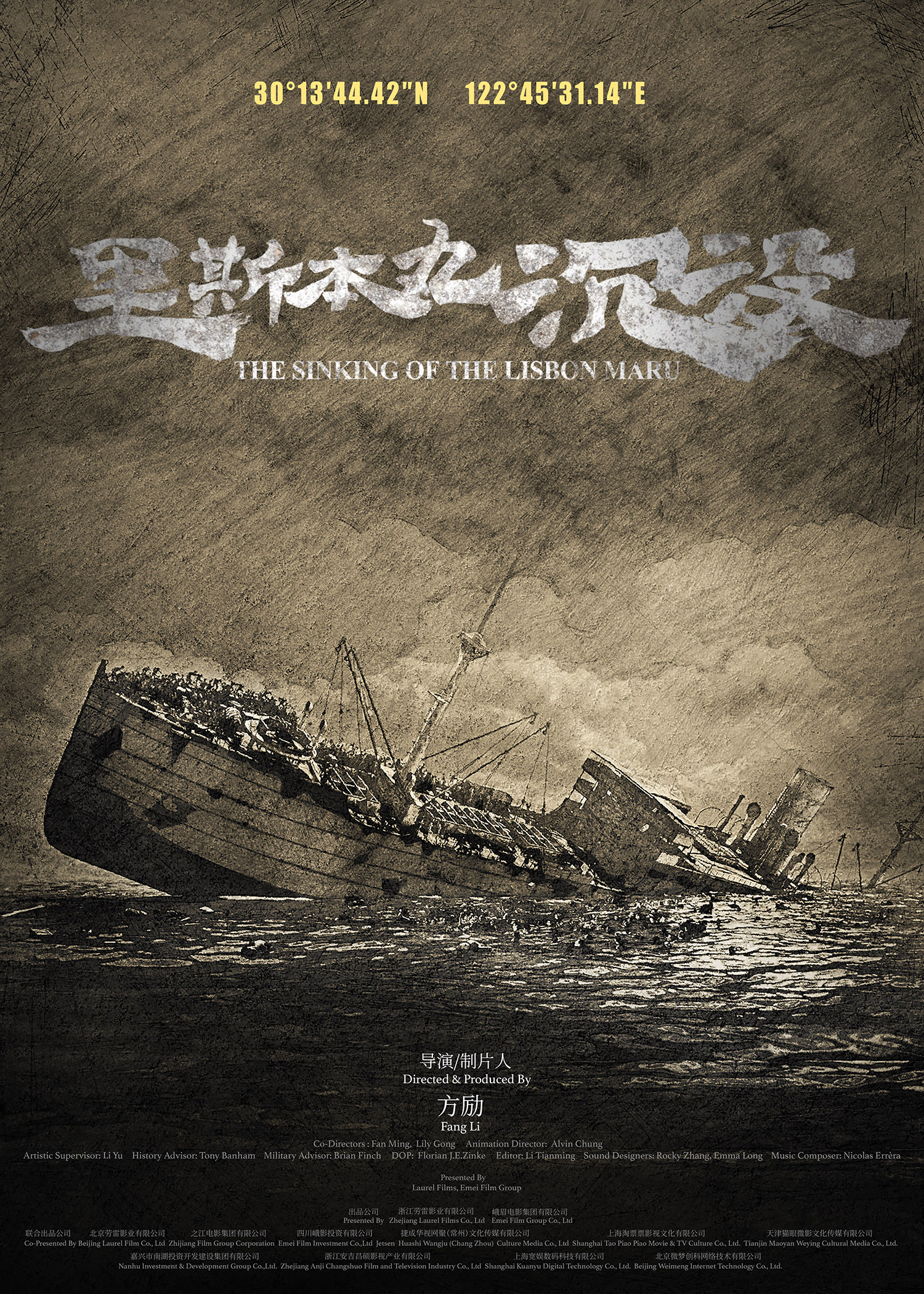

In recent years, there have been efforts to raise awareness about the rescue, including the documentary film The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru, which hit the big screen on Sept 6.

Filmmaker Fang Li spent eight years making the film. With rare footage and historical archives, the documentary tells the heroic and tragic story of both the lost and the saved lives.

Fang first heard about the tragedy in 2013 when he was on a boat heading from Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, toward Dongji Island while working on another film.

The island is the home of the fishermen who saved the British soldiers. The captain of the boat Fang was on pointed to the open sea and said the Lisbon Maru was lying underwater with hundreds of people trapped in the hold, but no one knew its exact location.

“From the moment I learned about this, out of curiosity, I was determined to find this shipwreck,” said Fang, who trained as a geophysicist in the 1980s and helped locate a plane’s black box in 2002 after it crashed into the Bohai Sea.

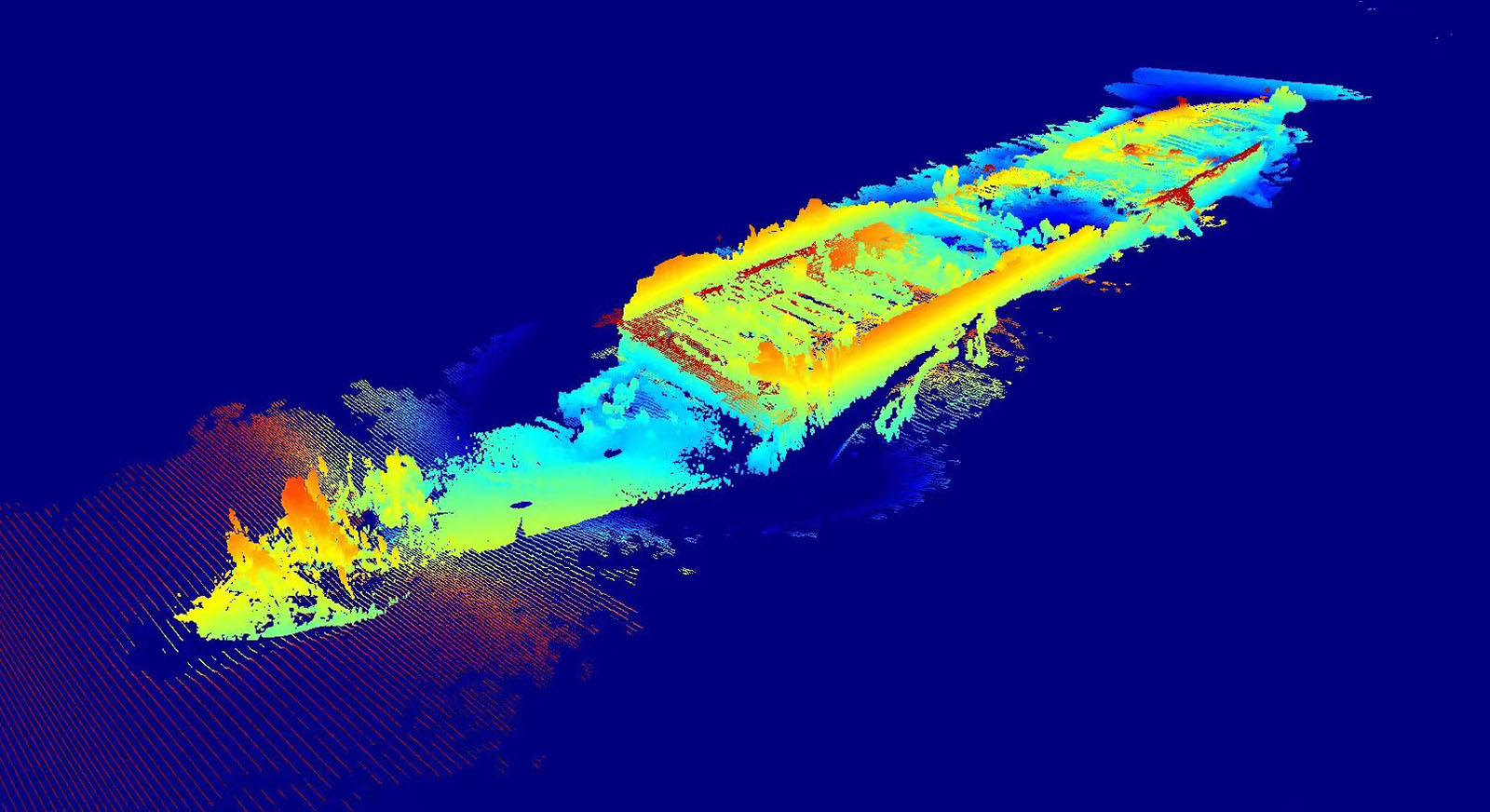

In 2016 and 2017, Fang carried out two surveys of the area and finally captured sonar images of a wreck that was 140-meters long and 40-meters wide, lying 30 meters below water. “We found it! I was quite proud about that,” Fang said.

The coordinates of the shipwreck — 30°13’44.42” N, 122°45’31.14” E — are printed on the film’s poster and also on the back of the T-shirts of Fang’s documentary team.

“After finding the ship, I wanted to find the survivors to understand their stories and what they went through 82 years ago. This is how the story was uncovered. Now, it’s time to share it with more people,” he said.

The story begins with the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in the winter of 1941.

At the time, Hong Kong was under British colonial rule with 15,000 troops stationed there. Hours after Japan’s strike on the Pearl Harbor US Navy base in Hawaii, on Dec 7, 1941, Hong Kong was also under attack.

The battle ended in 18 days with 8,500 Allied soldiers taken as prisoners. The next year, the Japanese army began transporting prisoners, including the Hong Kong POWs, in requisitioned civilian ships back to Japan as forced labor to repair roads, extend airports, and do other work to assist its military operations.

Because these transport ships were unmarked they became targets and some were hit by “friendly fire” from US submarines. Due to the cramped, inhumane living conditions onboard, they were referred to as “hell ships”.

Tony Banham, a British historian based in Hong Kong, has written about the wartime defense of the city. While doing research in the 1990s, he came across records of the deaths of more than 700 British Commonwealth soldiers marked as “lost in the Lisbon Maru”.

After further research, Banham located and interviewed a dozen survivors of the tragedy. With the material he gathered, in 2006 he published the book The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy.

He wrote that the number of those who perished on “this dirty little ship” was more than half the amount lost on the Titanic thirty years earlier, “but while the latter had spawned eternal interest and the world’s biggest box-office success, the former had been completely forgotten”.

When Fang made up his mind to make a documentary about the Lisbon Maru, he recruited Banham as a historical adviser.

But time was running out. When Banham began writing his book in 2003, there were only nine surviving POWs from the ship. By 2018, when Fang began filming, the number had dwindled to two.

Fang also enlisted Brian Finch, a retired major, as the film’s military advisor. Finch had served with one of the survivors and became interested in the incident. He translated A Faithful Record of the Lisbon Maru Incident, which was compiled by the Lisbon Maru Association of Hong Kong, from Chinese to English.

In April 2018, the documentary team embarked on its first trip to the UK, visiting 20 cities, and various museums and archives. They also interviewed the last survivor in the UK, Dennis Morley, who died in 2021 at the age of 101.

Morley was a 22-year-old in the Royal Scots regiment when he was put on the Lisbon Maru. After the war, he settled in Gloucestershire, England, and kept the horrific wartime story to himself.

But when he faced Fang’s camera, he recounted the horror that unfolded after the ship was torpedoed. The Japanese soldiers battened down the three holds the POWs were in, he confirmed.

“We were sealed in, we couldn’t get out anyway,” said Morley. “The water is pouring in. The bastards are going to drown us.”

In one hold, the ladder broke, trapping many of the Royal Artillery members. As the ship sank, survivors said they heard It’s a Long Way to Tipperary, an uplifting British marching song, being sung.

Some of the prisoners managed to escape and jumped into the water only to face a hail of machine-gun fire from other Japanese ships that had come to rescue their compatriots.

“The Japanese were shooting at them, and you swam among dead bodies,” said Morley. “Eventually, the Chinese fishermen came out and started picking up people, and then the Japs stopped shooting.”

Morley was picked up by one of the Japanese ships, but was grateful to the fishermen whose heroic actions prevented a complete massacre. “Those Chinese fishermen didn’t know that they saved a lot more people than they thought they saved,” he said.

Fang’s team also interviewed Lin A’gen, the last surviving fisherman, at the age of 95, on Dongji Island.

“Four men on a boat, (and) altogether some 20 to 30 boats went out,” said Lin, who has since passed away. “When people get in trouble at sea, we always go to help them, that’s very natural for us.”

The story of the Lisbon Maru has also been preserved by the local museum and studied by Chinese scholars. A document from the Zhejiang Provincial Archive declassified in 2005 detailed the rescue efforts.

After the fishermen saved 300 POWs, Japanese soldiers went to the village the next day and recaptured all but three who were hidden by the villagers in a cave.

Three Britons — J.C. Fallace, W.C. Johnstone, and A.J.W. Evans — escaped to Chongqing, China’s wartime capital. Through broadcasts, they disclosed the Lisbon Maru incident as well as the Japanese mistreatment of POWs, the first time this information was made public.

A record of that great rescue is kept in an exhibition hall in the Dongji History and Culture Museum. More than 400,000 visitors have visited the museum since it opened in 2009.

To find people connected to survivors of the sinking, Fang accepted interviews with the BBC, and bought full-page advertisements in The Times, Daily Telegraph, and The Guardian newspapers.

His team received around 300 emails — mostly from the children and relatives of the survivors — saying that they had heard the stories about the tragedy, and were eager to share them. From 2018 to 2019, the team flew to the UK four times and interviewed 100 families, filming hundreds of hours of footage.

In 2018, another survivor, 98-year-old William Beningfield was located in British Columbia, Canada. His memories were crystal clear, and the film documents his account of how the sinking unfolded.

Fang also interviewed the relatives of the US submarine engineer who fired the torpedo, and who lived with a sense of guilt after learning that POWs were onboard.

Striving for a full and fair account, Fang’s team overcame difficulties to locate the archive of the incident, in Japan. They interviewed the daughter of Shigeru Kyoda, the captain of the Lisbon Maru. Kyoda was imprisoned for seven years for his role in the incident following a post-war trial.

The team also interviewed Fumitaka Kurosawa, president of the Military History Society of Japan, who analyzed the intentions of the Japanese military commander Lieutenant Hideo Wada who gave the order to abandon the POWs.

In 2019, Fang organized for some of the relatives of the Lisbon Maru survivors to visit Dongji Island to meet the children of the fishermen. During the visit the families held a long-overdue memorial service at sea near the shipwreck.

In 2021, a memorial dedicated to the 828 POWs who perished, and over 200 others who died in captivity, was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, England.

In August last year, a special screening of the then-nearly finished documentary took place at the British Film Institute’s Southbank theater, in London, following delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The screening was for 400 relatives and friends of the Lisbon Maru POWs.

“When we filmed Morley, we promised that we would give him this documentary as his 100th birthday gift, but unfortunately we could not make it,” Fang said.

After the two-hour screening, applause erupted and many in the audience shed tears. Banham, the historian, said he could hear people sobbing from the moment the film started.

“The true story of war is grief,” Banham said. “It’s the impact on families. Many documentaries about war talk about the glamour of war, the aircraft, the tanks, the colorful explosions. But, the real long-term impact of war is on the families of those who were killed and those who survived.”

In June, the long-awaited documentary finally made its global debut at the 26th Shanghai International Film Festival. Of 450 films, The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru was chosen to open the festival.

Morley’s daughter Denise Wynne tearfully said after watching the film that “history should not be forgotten or distorted”.

Some family members of the fishermen were also present at the premiere, including Chen Xuelian, whose father steered a sampan to rescue several British POWs.

“I’m so excited to see my father’s image on the screen today. I’m so proud of his heroic acts,” said Chen.

Zhang Kun and Wang Xin in Shanghai contributed to the story.