Angolan writer of Portuguese-Brazilian origin talks about memory, forgetting and the significance of trying to understand each other, Yang Yang reports.

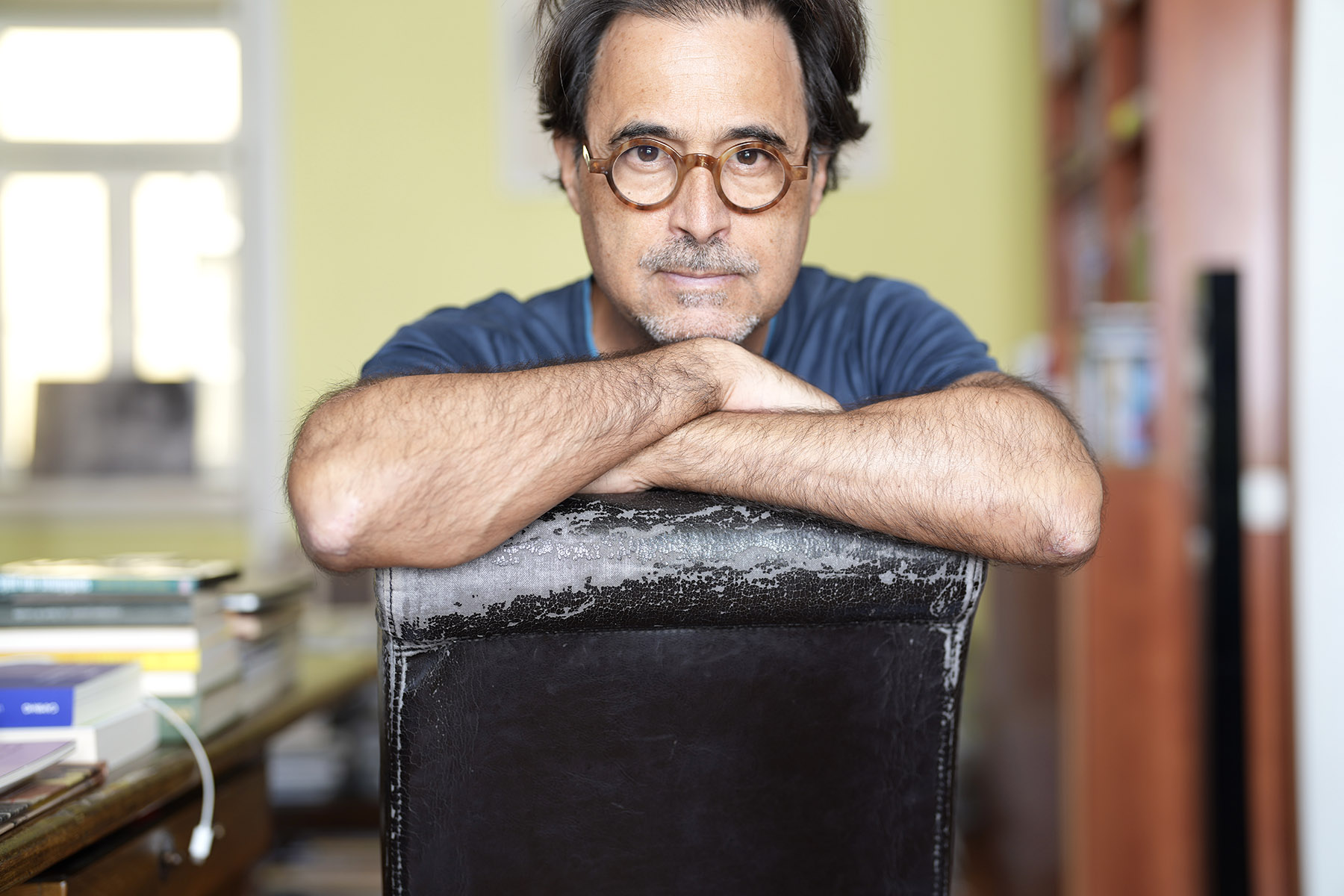

In mid-August, 64-year-old Angolan writer Jose Eduardo Agualusa paid his first visit to the Chinese mainland. Much as his writing, the trip to China was a journey across boundaries, both spatial and cultural.

Starting on the Island of Mozambique in northern Mozambique where he currently lives, Agualusa flew to the capital, Maputo, then to Lisbon, capital of Portugal, and then to Hangzhou in Zhejiang province, from where he took a train to Shanghai.

He had been invited to China as a guest of the international literary week at the Shanghai Book Fair.

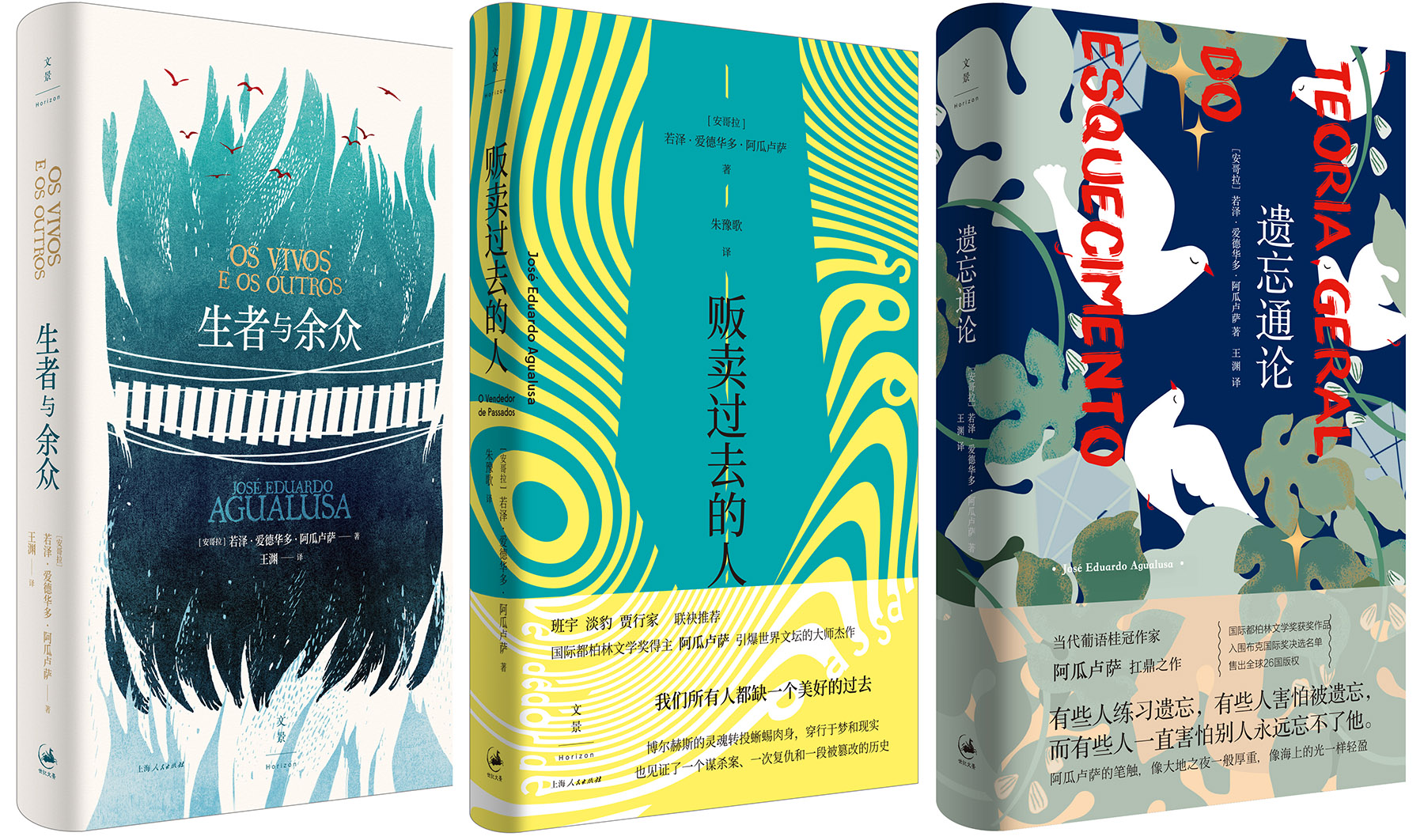

In Beijing and Shanghai, he encountered friendly people and keen readers whose questions showed that they had carefully read three of his novels that have been published in China.

These are A General Theory of Oblivion, winner of the International Dublin Literary Award in 2017 and shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize 2016, The Book of Chameleons, the first African winner of the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in the United Kingdom in 2007, and The Living and the Rest, which won the 2021 Portuguese PEN Prize.

READ MORE: Books, bags and lots more fun

Sun Ganlu, vice-president of the Shanghai Writers' Association, says that Agualusa's writing makes use of a calm voice, poetic language and a beautiful narrative rhythm to tell serious and cruel stories, a striking contrast that evokes complex emotions.

Agualusa was particularly impressed by the Shanghai Library East, which he compared to a trove in a forest.

When A General Theory of Oblivion won the International Dublin Literary Award in 2017, he said he wanted to use the prize money to help build a library on the Island of Mozambique, a wish he has not yet been able to realize mostly due to high property prices.

Like many writers, Agualusa also agrees that "a writer is first and foremost a great reader".

"To nurture a writing community, the first thing needed is to nurture a reading community. If you want to develop hundreds of writer communities, you need a library network," he says.

Agualusa says he was privileged because he grew up in a family which had a small library at home as both his parents, migrants from Brazil and Portugal respectively, loved reading.

Now, reading excerpts from favorite novels or pieces of poetry has become a ritual before he starts writing every morning.

Agualusa's interest in public libraries also stems from his concern about Angola's collective memory and identity.

"Memory is always related to identity, which has become an important problem for young countries like Angola. When I discuss the topic of memory in my writing, I actually want to explore the issue of identity," he says.

"We say when an old person starts losing memories, he or she actually starts disappearing, so does a country. Individuals' memories constitute the collective memory of a country," he says.

In countries such as Angola and Mozambique, decades of war have left people with many traumatic memories. Agualusa has found that people in different countries generally seek one of two solutions. Some choose to forget, to transcend the traumatic history, others keep the painful memories alive before learning to forgive. Agualusa does the latter through the help of writing.

"It is what everyone should do, first keep even the most painful memories, and then you are qualified to forgive," he said in an interview with the Book Review Weekly section of the newspaper The Beijing News.

"Only through memories can different sides in a war try to understand each other. In comparison, forgetting can lead to antagonism, especially fabricated forgetting," he said.

"In Angola, we are indeed facing a kind of identity crisis, which is actually due to a lack of a good memory-keeping mechanism, which includes literature, history, newspapers, magazines, and libraries, because identity is about everyday voices that should be preserved, and when this mechanism is lacking, it will cause problems."

Agualusa sees the hope of solving this crisis in young Angolan people, many of whom have shown an interest in his latest book Vidas e Mortes de Abel Chivukuvuku (Lives and Deaths of Abel Chivukuvuku).

It is a biography of an Angolan revolutionary fighter who experiences trials and tribulations throughout his life. It explores themes such as identity, politics and the human experience in the context of Angola's history and society.

"In this biography, I wanted to explore the problem of identity more. To my surprise, it has been well-received in Angola, the best of all my books, especially among young people," he says.

"People under 30 account for 70 percent of the population in Angola. As more young people are curious about the country's history, it's hopeful," he says.

At the Shanghai Library East, Agualusa delivered a speech titled The Boundary of Narration, in which he talked about his pursuit of writing, that is, to fight boundaries.

One of the boundaries is the one between "I" and "the other", which he says can be crossed through reading and writing.

In his most translated novel, A General Theory of Oblivion, an agoraphobic Portuguese woman named Ludo (short for Ludovica), who moves to Angola with her sister, bricks herself up in her apartment in Luanda for 30 years. Over the decades, the only way for her to "leave" is by reading the collection of books in the apartment.

"Reading liberated her and allowed her to get close to others," Agualusa said in the speech.

He emphasized this observation in a dialogue with Sun, saying that when people asked whether he felt foreign being in another country, he said that he didn't, because he was with readers, who were reading the same books by great writers such as Argentine poet and writer Jorge Luis Borges, and Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

"Reading the literature we love bridges our gaps," he said.

Through reading, people can stand in the shoes of others and feel their emotions, making the world a better place.

Writing has a similar effect, even more so, he said in the speech.

In 1989, Agualusa published his first book, A Conjura (The Conspiracy), a fictional documentary about a 1911 rebellion against Portuguese colonization, inspired by news stories written by Africans at the end of the 19th century.

"That led me to think about the anti-colonial war in Angola from 1961 to 1974," he told Wenhui Daily. After independence, a civil war broke out in 1975 and lasted until 2002.

"My country might have gone through the longest and cruelest civil war of the time. Why did that happen? My intuition told me that if I don't understand the past, I cannot understand the present," he said.

Writing the book allowed Agualusa to better understand the falsifications and terms colonizers and warlords devised to incite antagonism and suppress goodwill and understanding between people.

Through his writing, he manages to counter these sly verbal tricks, listen to the voices of others, step into their skins, feel their heartbeats, and shed their tears, even if they were supposedly "enemies".

"Writing strengthens the muscles of empathy," he said in the speech.

To provide readers the context to understand "the other", the main mission of a writer is to try to become "the other", Agualusa says, adding that "the beauty of writing lies right in this eternal attempt to become 'the other' — young or old, man or woman, individuals of human or other species".

For example, The Book of Chameleons is narrated in the voice of a lizard.

"As I grow older, and have experience of different places, I increasingly feel that 'the other' is us, and we are 'the other'. The boundary between the two is dynamic," he says, "and getting to know 'the other' is a process of self-discovery, and vice versa."

To become "the other", the first thing is to listen and talk to them, to try to understand them.

In A General Theory of Oblivion, he portrays a police officer who has tortured criminals.

"It's more difficult to understand a bad person, but one of my pursuits of writing is to find the humanity in bad people," he says.

Another boundary the writer has been trying to cross in writing is the one between fiction and reality.

In The Living and the Rest, for example, writers and poets from different African countries come to the Island of Mozambique for a literary week. As the story develops, writers meet characters from their books in the fictional reality.

Some critics categorize Agualusa's style as magic realism, although the author strongly disagrees.

Magical realism is a storytelling approach often used in Latin American literature, where fantastical or mythical elements are matter-of-factly woven into otherwise realistic narratives. It is seen as an effective strategy allowing writers to examine problems in post-colonial societies.

"When I read Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the master of magical realism, I feel something very familiar and real in his work," he says.

Agualusa found evidence in Marquez's visit to Angola to support this feeling. In 1977, two years after Angola's independence from Portugal, the Colombian writer was invited to visit the country to write about its community of Cubans. In Angola, Marquez found a universe similar to his childhood in Latin America.

ALSO READ: Rome poetry festival to mark chapter of success

"That's why I say there is something very similar between South American and African cultures," he says.

Agualusa says he does not like to be labeled.

"What they call magic realism is actually everyday life in Africa, so I prefer to define it as African realism," he says, adding that "some African writers call it animism instead".

"In The Metamorphosis, Franz Kafka turned a person into a gigantic insect. In The Living and the Rest, I wrote about a woman transforming from a cockroach. People call me a magical realist, but nobody labels Kafka that way," he says.

"This kind of label sometimes restricts our recognition of literature, and it is what a writer needs to break," he says.

Agualusa closed his speech by saying that writing transcends the boundaries of possibility. "The impossible paths, the paths that frighten us, are the only paths worth exploring for writers. Writing — like all journeys — is about seeking wonder. I believe that the only limit for writers is their imagination."

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn