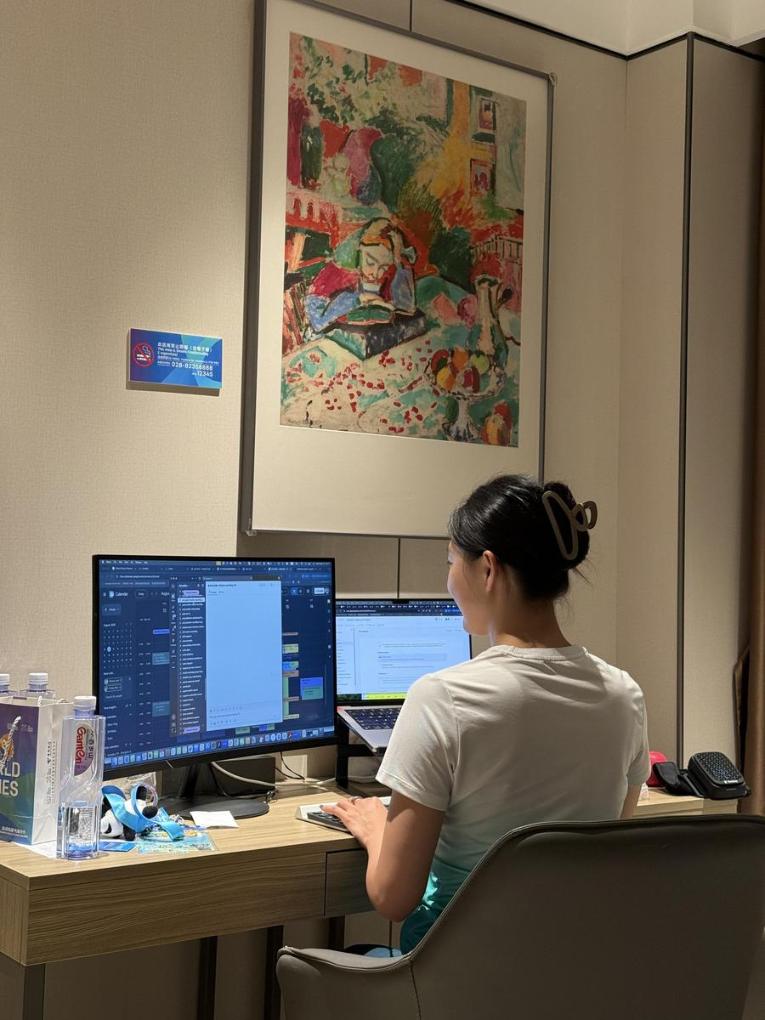

CHENGDU - Less than 24 hours after Tang Ke completed her journey at the Chengdu World Games, she was back in her office in Shanghai for meetings. After the freediving events concluded on Monday, Tang's immediate focus shifted from pool lanes to project timelines.

"I'm heading back to Shanghai to work. My leave ends today," Tang said, adding with a touch of wry humor familiar to any working professional: "This morning I was still thinking, my PowerPoint isn't finished yet!"

Tang's Chengdu campaign started on Sunday in her strongest event, the women's dynamic without fins. Anticipation ran high, yet her quest for a personal best ended in heartbreak as she was disqualified for failing the surface protocol.

ALSO READ: Cai’s passion for fireworks helps kick off World Games with bang

"I had good movement, rhythm, and efficiency today. I just didn't time the surfacing quite right," she admitted.

Her performance, she believed, fell short of her training peak, likely due to the unique pressure of competing on home soil: "So it's quite regrettable; maybe it was because being the host added some extra pressure."

The sting of the disqualification shaped her approach the very next day in the dynamic with fins event. Shifting focus from pushing limits to securing a clean finish, Tang surfaced conservatively, achieving a distance of 200.00 meters and 10th place.

"Today, I mainly surfaced cautiously to get a white card because I didn't get one yesterday," Tang explained. While the overall result wasn't what she envisioned, Tang found profound meaning beyond the rankings.

She highlighted the groundbreaking performances of Chinese para athletes - four gold medals, and the gathering of elite talents. "We had multiple women world record holders here. Competing alongside them on the same stage is an honor."

Tang's path to The World Games pool began just three years ago, driven by a familiar urban malaise: work stress. A software product manager in the demanding world of cross-border fintech, she sought an outlet.

"I started freediving three years ago because of high work pressure," said the 31-year-old. Having swum competitively until middle school, the water called her back. And the rediscovery quickly evolved from hobby to passion.

"I gradually got to know friends in the competitive circle and started training competitively with my coach, Jin Ming," she shared. Her debut at the World Championships three years ago ignited a deeper commitment: "I got more and more into it because I really love this sport, where you push your limits on the competitive stage."

Athletes with full-time day jobs, Tang and her coach Jin, who also competed at the ongoing Chengdu World Games, carve out time when and where they can while balancing work and training. "We have to squeeze out one or two days a week to train alongside our jobs."

"I often carry my dive bag to work in the morning, finish meetings late, have dinner, then head straight to the pool, train from 9 to 11 pm," Tang introduced her challenging routine.

The aftermath, though, is physiologically taxing. "After breath-hold training, it puts a lot of strain on the nervous system. I often can't sleep. Getting out of the water at 11, home by midnight, then tossing and turning until 2 or 3 am, only to get up at 9 the next day for work."

Still, she credits freediving with transforming her life: "Overall, my lifestyle has become healthier. I consciously adjust my diet, sleep and schedule, to make time for strength and pool training." The challenge surprisingly fuels her at the same time: "It's tough. But the process, I would say, is challenging and makes you want to keep pushing your limits."

For Tang, freediving is more than just physical achievement, but rather a profound internal journey. "I think freediving is a conversation with yourself," she said. "It's a sport where physical ability accounts for 30 percent, and mental strength makes up the rest 70 percent."

"Unlike other competitive sports, once you enter the venue and slip into the water, it's truly just the water and yourself," Tang said of the unique solitude of freediving that captivated her. "Only the sound of the water and the feedback from your own body, whether it's muscle lactic acid or mental resistance, sometimes even entering a flow state. It's an intensely personal sport."

While safety concerns often surround the discipline, Tang emphasized its protocols. "The first rule of freediving is never dive alone. We have trained buddies who know how to perform emergency rescues."

She then spoke candidly about pushing to the edge, describing the disorienting experience of low oxygen - brief unconsciousness, fragmented memories, and the resigned realization upon being revived: "I saw the 175-meter line, and then suddenly lost consciousness. When I was awakened, I saw a safety diver I knew and thought, 'Oh no, I blacked out again.'"

She sees the intense demands of elite freediving not as a separate world, but as an amplified version of the daily grind.

"It's similar to everyday workers going to the gym after work. It's about time and energy allocation. But now, because I have higher demands, I might put unconscious pressure on myself."

"From an athlete's perspective, the results are somewhat disappointing," Tang admitted, yet her perspective widened beyond personal metrics. "But from the standpoint of raising awareness for freediving, it's a fantastic opportunity. I think freediving might be about to take off."