This week we start a series celebrating Hong Kong artists who pulled off a remarkable feat this year, producing new works that are fresh, clever and compelling, this first installment features new media artist GayBird, whose Music for 9 highlights the fragmented nature of our everyday existence while also suggesting that it’s possible to find purpose and meaning in it. Chitralekha Basu reports.

In Music for 9, new-media artist GayBird, or the back of his head, appears on a digital screen, conducting an atonal rendition of Beethoven’s Symphony No 9. (ANDY CHONG / CHINA DAILY)

In Music for 9, new-media artist GayBird, or the back of his head, appears on a digital screen, conducting an atonal rendition of Beethoven’s Symphony No 9. (ANDY CHONG / CHINA DAILY)

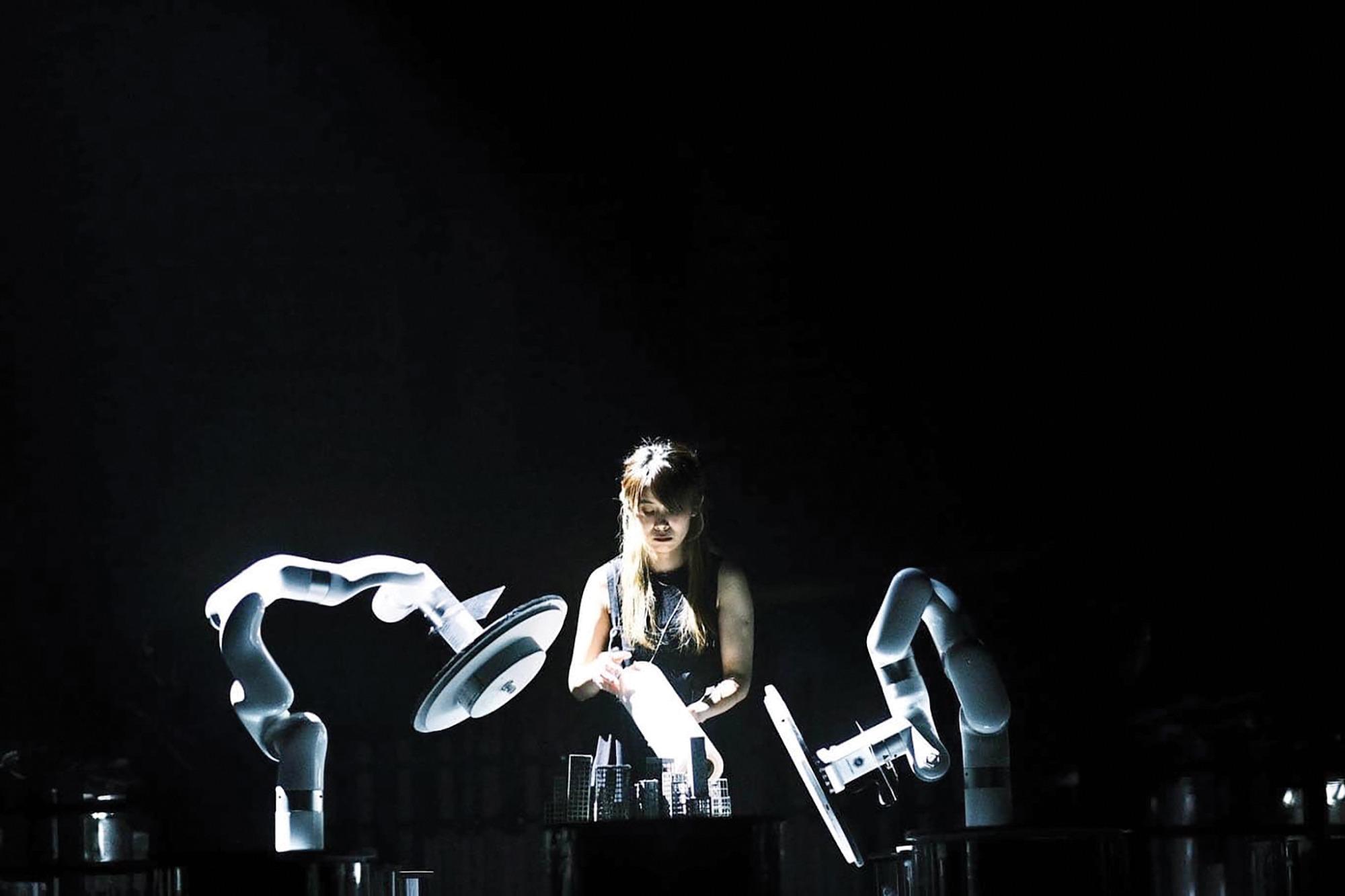

Leung Kei-cheuk, better known by his nom de plume, GayBird, is enjoying his moment in the sun. In May the composer, musician and new-media artist from Hong Kong presented a concert at Taichung National Theater in Taiwan. Called One Zero 2.0, the piece saw a couple of robotic arms literally lending a hand to the human variety of the musicians. The show touched unprecedented heights of robot-human collaboration and is still trending on social media.

No stranger to conducting orchestras, GayBird’s sound installations often emulate the classic seating pattern of a musical ensemble, with devices replacing musicians. The orchestral look and feel of his installations could be a reflection of what Yip Yuk-yiu, associate professor at the School of Creative Media, City University of Hong Kong (CityU), identifies as GayBird’s collaborative spirit. Yip points out that increasingly, media art is becoming a collaborative field, and GayBird, he says, “is very good at collaborating with different talents”, be it humans or machines.

Take A Grandiose Fanfare at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, for instance. The audio-visual installation, comprising an interactive 31-channel sound system, attempts to re-create the sound of fireworks celebrating the city’s return to the motherland on July 1, 1997. A bunch of speakers are placed inside a circle not unlike an orchestra pit, with the largest among them standing upright, holding center stage. The analogy with human orchestras is complete when the speakers, smart devices as they are, start reacting, visually, and aurally, to the presence of an audience.

The exhibition is laid out like an orchestra, with each of its nine speakers contributing a sound to make the music. (ANDY CHONG / CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition is laid out like an orchestra, with each of its nine speakers contributing a sound to make the music. (ANDY CHONG / CHINA DAILY)

A Grandiose Fanfare is one of GayBird’s three ongoing exhibitions in Hong Kong, one of these being his tribute to Joan Miró. Part of a major Miró exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, Bird Code takes its cue from the 20th-century Spanish master’s style of painting birds as imperfect geometric shapes with a few mysterious squiggles thrown into the mix. Using artificial intelligence, GayBird has turned the chirping of birds into a set of sounds and symbols. Visitors can sit down at telephone-booth-style stations to listen to AI readings of bird sounds, even gain some insight into the creative process.

Just last week he won an Asian Cultural Council fellowship that will help support his upcoming field trip to Japan and South Korea. GayBird means to find out about the latest trends involving art and technology in those countries, with a view to developing new creative practices that work best in his own cultural context.

Such pursuits might be just what Hong Kong needs, if artists are to take advantage of the local government’s promise to allocate generous funds to support “art tech”. A tad skeptical about the art-tech label (“it seems to suggest that it is the technology that’s creating such art when technology is just a tool”), GayBird has been applying advanced technology with great ingenuity to make art for at least two decades.

Music for 9, his most-recent multimedia installation, laid out across two rooms on the 17th floor of Central’s vertical art gallery hub H Queen’s, uses technology to highlight, question and critique its firm grip on our lives. The piece is more abstract, varied, complex and somber in tone compared to the artist’s previous works, many of which can be enjoyed for their joyous vibe, lively foot-tapping, or rousing, music and jaw-dropping immersive visuals, without necessarily having to go into the depths of the philosophical ideas behind them. By contrast, Music for 9 demands greater engagement on the part of its audience. The piece holds a very special place in GayBird’s oeuvre, standing out in terms of scope, ambition and execution. It could be a career milestone worth celebrating.

GayBird’s immersive audiovisual installation Bird Code invites the Hong Kong Museum of Art visitors to experience how artificial intelligence reads bird sounds. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

GayBird’s immersive audiovisual installation Bird Code invites the Hong Kong Museum of Art visitors to experience how artificial intelligence reads bird sounds. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Open to possibilities

Music for 9 calls attention to the abrupt and disjointed nature of our experience of the present-day world. “We’re living in an extremely fragmented time. As much of our time is spent scrolling digital media, we normally see only parts of a thing,” explains the artist. However, his aim is to create something constructive and meaningful by “connecting these fragments”.

He chose the number 9 as a symbol of incompleteness, being one short of the perfect 10. “At the same time, by being incomplete, it suggests an openness to possibilities. So, in a sense, the number 9 resonates with the general nature of human existence.”

Six digital screens, separated from and standing perpendicular to their light source, are laid out on the floor of the main exhibition room. “We separated the screens from their light source to create a new dimension, offering the audience a new perspective,” GayBird remarks. Each of these screens displays a hand or foot in motion, visually representing the movements of the 10-minute composition specially created for the exhibition.

“I think the most authentic instrument a human being can use is their body,” says the artist, explaining why he chose to present an atonal rendition of his composition, with the musical movements represented through gestures by percussionist Emily Cheng Mei-kwan and him. Another split digital screen placed atop a cage shows the back of GayBird’s head as he is conducting an orchestra. Though the images of hand and foot making music remain anonymous, the composer-conductor is easily identified by his signature mushroom-cut hairstyle.

A Grandiose Fanfare at the Hong Kong Palace Museum re-creates the sound of fireworks to mark Hong Kong’s return to the motherland in 1997. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A Grandiose Fanfare at the Hong Kong Palace Museum re-creates the sound of fireworks to mark Hong Kong’s return to the motherland in 1997. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

He is often a physical presence in his own works, not just controlling and orchestrating the music, but playing instruments as well. The reason for this, more often than not, says the artist, “has to do with limitations of budget and time” rather than a desire to make an appearance. “I don’t mind being a performer in my own piece, but if I had more resources and a bigger budget, I’d get more professional people to do it.”

His composition for Music for 9 is bookended by Beethoven’s Symphony No 9, though this may not be immediately discernible. The first rendition is simply the sound of hands clapping, keeping the rhythm of the score, while the second comprises sounds made by body parts articulating the musical movement.

“Symphony No 9 is Beethoven’s last complete choral symphony, composed at a time when he was almost deaf. So there was a sense of incompleteness about it,” GayBird points out. “I tried to interpret the piece by using sounds made by movement of body parts and without tonality,”

Even as this atonal piece, which, at least in parts, can sound like harsh and relentless clanging of metals, not unlike the sort heard in a shipbreaking yard, plays on a loop, a robot dog inside the aforementioned cage keeps pacing around, recording its surroundings, including visitor movement, using a camera on its back. The images are projected live on a wall. A two-channel video in the smaller exhibition room displays an animated unidentifiable mass floating across both screens. It is a composite made out of leftover footage from the videos on display in the main room, moving in sync with the amplified sound of the artist’s own pounding heartbeat.

“There are multiple sources of moving images scattered all around the space — a bit like our everyday experiences these days,” says GayBird, who believes visitors are likely to take away vastly different experiences from the exhibition. And that is perhaps the point of the show. “Most of my works are meant to encourage the audience to think of their everyday existence in a different way, find more possibilities for themselves as well as the world. I prefer my audience to interpret my works any way they like.”

There’s still more to see and ponder about in Music for 9. For GayBird’s elaborate ode to imperfection is made up of elements that, according to the artist, are “varied, disparate and incomplete and yet suggest some kind of a whole when presented in the same space”.

GayBird touched new heights of robot-human collaboration at the One Zero 2.0 concert in Taiwan. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

GayBird touched new heights of robot-human collaboration at the One Zero 2.0 concert in Taiwan. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

One such vital yet somewhat incongruous element of the show are six drawings based on his composition. In them, GayBird mixes the symbols of music notation with Braille characters. The idea was to “deconstruct, or disassemble, the standard lexicography of music notation” by separating the notes, beats and slurs and removing the rest symbols from the first five drawings. The introduction of Braille characters underscores, once again, the main theme of rupture and disintegration for “unlike the original Braille alphabet, these drawings are not tactile, and that makes them incomplete, in a sense”.

Music for 9 appeals to CityU academic Yip for “its sense of hybridity of form and technical media”. “The work is playful, theatrical, musical, sculptural and beyond,” he adds. “Also it employs a variety of technical components — video, audio, photography, robotics and drawing.”

Yip traces GayBird’s love of putting together the unlikeliest of materials and forms to the artist’s “curiosity and eagerness to learn new things”.

GayBird agrees. His increasing love of AI, which he sees as a useful, practical, tool, grew out of the wish “to learn something new from the technologies I use. That’s where my inspiration comes from.”

There might be a number of reasons that inspired the tonal shift in Music for 9. It feels more minimal and contemplative compared to GayBird’s earlier works evoking a celebratory atmosphere. Its understated, near-monochromatic color palette might have something to do with the time in which it was birthed, in a world still not out of the shadows of the pandemic and one in which the absence of friends who have left the city is deeply felt by those who chose to stay behind.

Yip, however, contends that “underneath the seemingly playful, stylish and sometimes light-hearted presentations, GayBird’s works have always been serious”. Only that with Music for 9, the artist might have embraced a “cleaner, quieter, more minimal aesthetic”. The packaging might have gotten a bit less colorful, but the intent remains constant.