Ennio, written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Starring Ennio Morricone, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood and Wong Kar-wai. Italy/Belgium/Japan, 156 minutes, IIB. Opens June 1. GBA briefs

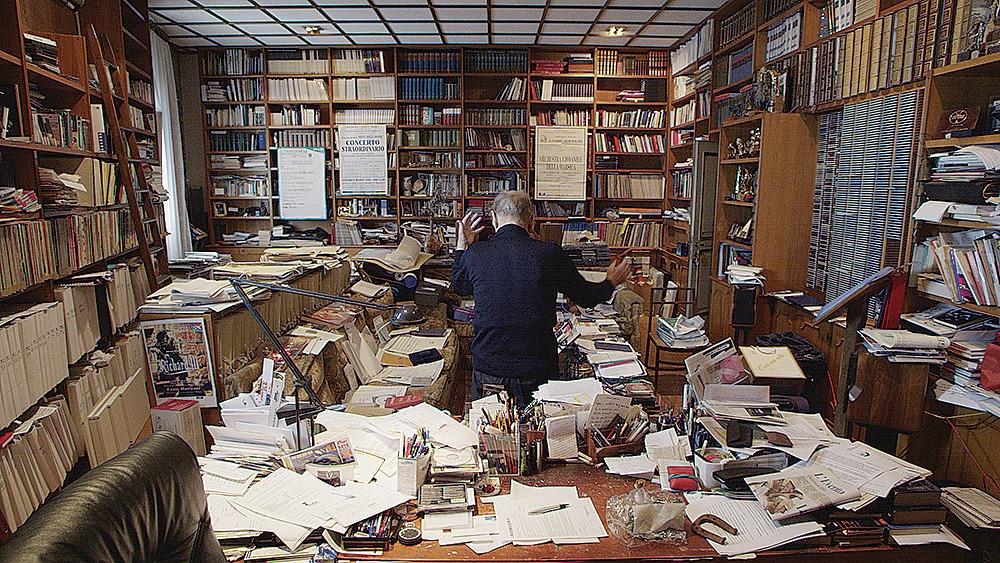

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ennio, written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Starring Ennio Morricone, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood and Wong Kar-wai. Italy/Belgium/Japan, 156 minutes, IIB. Opens June 1. GBA briefs

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Most regular moviegoers are able to identify cinema’s most notable scores and themes when they hear them. Few among us wouldn’t be able to name the film on hearing the main strains of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Star Wars (1977–), Jurassic Park (1993–), the refrain from The Godfather (1972–90) or Titanic (1997), the rapid and relentless plucking of violin strings in the shower scene in Psycho (1960), the eerie chirp of Halloween (1978–2022) or the bassy rumble of Jaws (1975–87). Some argue that a score is like editing: If you notice it, it’s not very good.

Italian director Giuseppe Tornatore, who burst onto the world stage in 1988 with his Oscar-winner Cinema Paradiso, puts paid to that notion in Ennio, his exhaustive documentary about one of cinema’s greatest composers, Ennio Morricone (who, incidentally, scored Paradiso). Several among Morricone’s 530 IMDb credits — The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), The Battle of Algiers (1966), Days of Heaven (1978), The Mission (1986), In the Line of Fire (1993), The Untouchables (1987), The Hateful Eight (2015) — are permanently etched in popular psyche. The composer died in 2020 at the age of 91.

Ennio the film is of several minds, but somehow they all work together. The music literates among us will have a field day listening to Morricone, as well as a who’s who of 20th century writers and musicians, break down some of his most iconic pieces on a technical level. Tornatore revels in the minutiae that made Morricone’s work so distinctive. Happily, for the most part, enough lay terms are bandied around to explain to the uninitiated exactly why Morricone’s work was so innovative, and place him in the larger context of film music.

Ennio, written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Starring Ennio Morricone, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood and Wong Kar-wai. Italy/Belgium/Japan, 156 minutes, IIB. Opens June 1. GBA briefs

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ennio, written and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Starring Ennio Morricone, Quentin Tarantino, Clint Eastwood and Wong Kar-wai. Italy/Belgium/Japan, 156 minutes, IIB. Opens June 1. GBA briefs

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

At the outset, Morricone resisted working in film because it was considered lowbrow in the 1960s but eventually went on to write the music for director Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns, which made them both famous. In Ennio, comments from dozens of artists ranging from ’60s Italian pop star Caterina Caselli to Metallica’s James Hetfield, directors Wong Kar-wai and the Taviani brothers (1982’s The Night of the Shooting Stars), and scorers like Hans Zimmer and John Williams who followed in Morricone’s footsteps explain why the composer is such a titanic figure.

The film also offers a fantastic crash course in Italian cinema from the post-World War II neorealist movement until the present day, and demonstrates what most of us intuit when we’re watching a film but don’t know how to articulate: How a score can work toward storytelling beyond signaling tension or death. For instance, Clint Eastwood’s man-with-no-name antihero (in Leone’s Dollars trilogy) would be half a character without the iconic whistle that’s his signature, and for Morricone, that’s just one of many.

If there’s a missing element to Ennio, it’s the lack of real insight into what makes Morricone tick as an artist. As a subject, he remains something of an enigma. Despite the film’s first hour or so being dedicated to his childhood and education, there’s not a lot of detail about Morricone’s relationships with his trumpeter father (perhaps it was complicated, we never really find out); with his most influential teacher, composer Goffredo Petrassi; or with Maria, his wife of 63 years, and often a crucial partner in his work. A few interviewees offer some pop-psychology theory, but the topics are never addressed by Morricone himself. Maybe none of that matters because when taken in at a cinema, where it’s meant to be experienced, his music speaks for itself.