Speculation and the post-lockdown rebound have propelled a number of Chinese artists into the blue-chip bracket. Joyce Yip looks for answers to whether this is all sustainable.

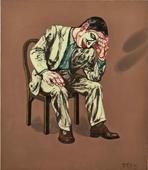

Mask Series No. 18 by Zeng Fanzhi. The latter fetched the highest auction price for a piece of Chinese contemporary art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mask Series No. 18 by Zeng Fanzhi. The latter fetched the highest auction price for a piece of Chinese contemporary art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

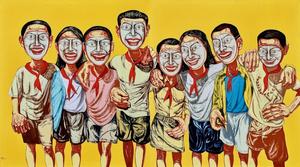

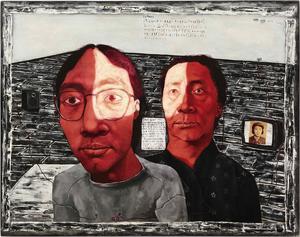

A bright green German Shepard, a blindfolded dancer, and an eclectic interpretation of Van Gogh’s self-portrait — all of these images have one thing in common. They are works by Zhou Chunya, Zhang Xiaogang and Zeng Fanzhi — contemporary Chinese artists who made it to the 2020 Blue Chip Artists Index compiled by Artprice, one of the world’s leading resources of art market information.

The names make up half the living artists on the list, released by ArtMarket.com in March — a testament to their escalating demand in the past year.

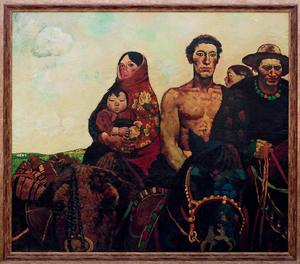

The addition of Zhou, Zhang and Zeng is well deserved. Known for his monochromatic figures with prominent, often emotionless eyes, Zhang set a personal record with his career-defining Bloodline Series: The Big Family No. 2 fetching US$12.5 million at a Christie’s auction late last year. Meanwhile, Zhou’s Spring is Coming — showing a Tibetan working-class family in the process of migration — sold for US$12.45 million at a China Guardian auction in August, setting yet another personal record. Finally, Zeng’s Mask Series 1996 No. 6 oil on canvas fetched US$23.3 million in Beijing, topping auction prices of Chinese contemporary art pieces.

Mask Series 1996 No. 6 by Zeng Fanzhi. The latter fetched the highest auction price for a piece of Chinese contemporary art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mask Series 1996 No. 6 by Zeng Fanzhi. The latter fetched the highest auction price for a piece of Chinese contemporary art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

According to the Art Market 2021 report published by Art Basel and UBS, works by living artists in 2020 accounted for close to half of the value of sales in the Post-War and Contemporary sector, up 5 percent in year-on-year share.

Call it COVID-collecting or revenge buy, 2020 was a boon for blue-chip artists as a third of the high-net-worth collectors who figured in “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Gallery Sector”, a 2020 mid-year survey, showed significantly more interest in art than before. And although speculative buying by a pool of collectors who seem to be getting increasingly younger played a major role in turning the spotlight on Chinese contemporary artists, this is a category that seems destined for a long run, given its relatively accessible asking price and shorter resale period.

The Art Market 2021 report attributes the skyrocketing performance of contemporary Chinese art pieces on home turf to China’s success with containing the spread of COVID-19 in the latter half of 2020 plus a resolution of VAT issues last May that now allows auction houses selling art to issue full invoices, which may have stimulated some sales.

Known for his green dog series, Zhou Chunya’s Spring is Coming fetched US$12.45 million at a China Guardian auction in August 2020, setting a personal record for the artist. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Known for his green dog series, Zhou Chunya’s Spring is Coming fetched US$12.45 million at a China Guardian auction in August 2020, setting a personal record for the artist. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Known for his green dog series, Zhou Chunya’s Spring is Coming fetched US$12.45 million at a China Guardian auction in August 2020, setting a personal record for the artist. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Known for his green dog series, Zhou Chunya’s Spring is Coming fetched US$12.45 million at a China Guardian auction in August 2020, setting a personal record for the artist. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Soaring superstars

“If you ask a collector, they’ll never say they purchased art for speculation,” said Clare McAndrew, founder of the art research firm Art Economics, who put the Art Market 2021 Report together. “But if somebody is turning around a piece in an auction in a year to three years, it’s speculation. These aren’t old buying-and-selling models of collectors buying and holding art to donate or bequeath to their kids. Instead, they’re buying and selling within a year in auctions.”

The implication of this, she adds, is that auction houses have become the battleground for resale as they morph from a secondary-market structure into not only an ecosystem “very similar to a primary market”, but also take on the role of a dealer — thus further exacerbating the top-heavy bias she calls the “superstar phenomenon”.

“This is prevalent in China where artists try to sell directly to the auction sector,” she said. “Artists are being pushed into the resale market quite quickly where there’s more liquidity. Especially during crisis and uncertainty in the market, people stick to what they know and what they see their successful peers doing. This is how we get the superstar phenomenon. Investors and collectors don’t want to make a mistake or look like they’re doing the wrong thing.”

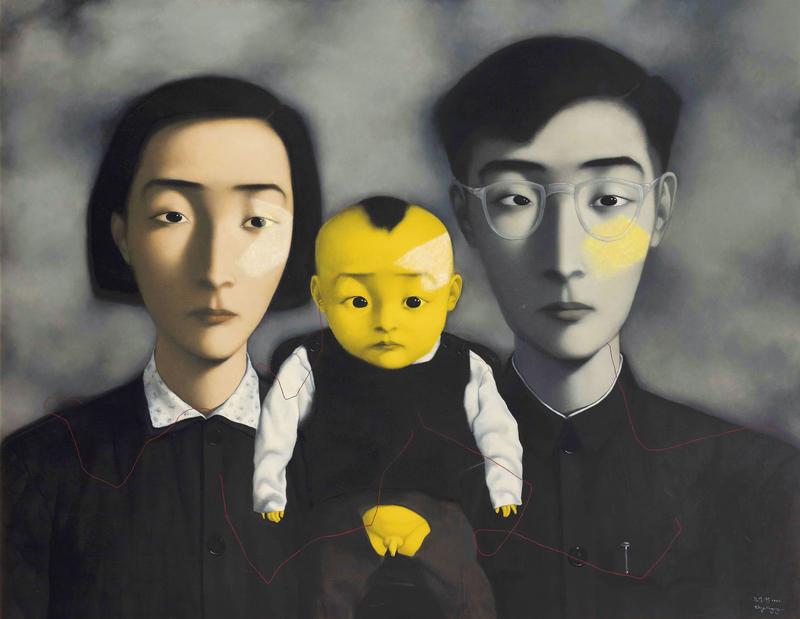

Mother and Son No 1 and The Big Family No. 2 from Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series. The latter earned US$12.5 million at a Christie’s auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mother and Son No 1 and The Big Family No. 2 from Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series. The latter earned US$12.5 million at a Christie’s auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mother and Son No 1 and The Big Family No. 2 from Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series. The latter earned US$12.5 million at a Christie’s auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mother and Son No 1 and The Big Family No. 2 from Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline series. The latter earned US$12.5 million at a Christie’s auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The good news, however, is that speculative mega-transactions that make it to mainstream media coverage are indeed rare. The Art Market 2021 Report further reveals that 92 percent of sales in the wider Post-War and Contemporary sector actually fetched prices less than US$50,000. Albeit the loud noise generated by the likes of Zhou, Zhang and Zeng, the sale of pieces priced over US$1 million account for just over half of the market’s value in less than 1 percent of the lots sold.

“There is a spectrum of collectors, from purely financial to purely aesthetics,” said McAndrew. “Most people are somewhere in the middle no matter where they’re from, and frankly, this is the sensible place to be. You don’t want to spend a lot of money on something that won’t go up, and also not on something you don’t truly enjoy. That’s how the market should be.”

Art trade analyst Clare McAndrew says during a time of uncertainty, such as the one caused by COVID-19, collectors tend to go for the “superstars” among artists. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Art trade analyst Clare McAndrew says during a time of uncertainty, such as the one caused by COVID-19, collectors tend to go for the “superstars” among artists. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Leo Xu, senior director at David Zwirner Hong Kong and founder of the now-defunct Leo Xu Projects gallery in Shanghai which has helped bring young Chinese artists to the fore, agreed, saying that a speculation-driven market disassembled after investors had learnt their lesson from the 2006-07 boom.

His sentiments are backed by the Art Market 2021 Report, which indicates that while the collectors on the Chinese mainland — the biggest clientele for Chinese contemporary art — remain optimistic about the growth of the global art market in the next 10 years, they are not that keen to make short and medium-term investments right at this moment.

“Chinese collectors have learned their lesson from the past decade, when works fluctuated and devalued. So people aren’t stupid to buy art just for short-term investments anymore,” he said, adding that revenge buying during the height of the pandemic in 2020 only dialled up the existing spotlight on Chinese contemporary artists.

Leo Xu of David Zwirnir Gallery in Hong Kong says revenge buying during the pandemic helped dial up the popularity that Chinese contemporary art was already enjoying. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Leo Xu of David Zwirnir Gallery in Hong Kong says revenge buying during the pandemic helped dial up the popularity that Chinese contemporary art was already enjoying. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

What the future holds

“There’s a deep insecurity among artists to catch up with the rest of the changing world but making art is not really about changing every minute,” said Xu. “I feel we are in a better position with museums and fairs returning,” he said, adding these offer artists a scope for getting inspired and seeing their own works in the wider context while connecting with international dealers rather than waiting for people to visit them.

“There really wasn’t a concept of Chinese contemporary art until recently, so it’s normal for Chinese artists to compare themselves with others — whether I can paint like that, use such mediums — but if they have a chance to broaden their horizons, their craft should come naturally.”

While he applauds artists trying to connect with buyers online, Xu thinks the next step is establishing an institution in which curators, writers, dealers, researchers and managers can work together. Existing fellowships at national museums in Beijing and Chengdu are a good start, he said, hoping such efforts will continue as more overseas-educated enthusiasts return to China and contribute to the art scene.

McAndrew agreed, hoping a diversification of resources can dissipate the current superstar phenomenon and restore in collectors — both seasoned and new — a confidence in their own taste for art. Given the growing number of emerging artists being promoted by art dealers and galleries at the moment, such optimism might be based on solid foundations.

No market can be fueled by speculation alone. Though COVID-collecting has notched up the prices of certain categories of art and works by master painters, the market for Chinese contemporary art has been growing at a steady pace in the past decade and will probably continue to do so as long as collectors make informed choices.